Parents are pushing back after a committee whose members sit on a Wisconsin school board did not move forward with approving a book about Japanese American incarceration during World War II for a sophomore English literature class.

The backlash comes after Muskego-Norway school district board members said that the inclusion of the book would require “balance” with perspective from the U.S. government, according to two parents in the district. They also tell NBC News that minutes from a heated meeting with board members on the topic were not posted, and a video of another board meeting was reportedly edited.

“She clarified and said that she felt that we needed the perspective of the American government, and why Japanese internment happened. And so then again, we had raised voices at this point. I told her specifically, I said, ‘The other side is racism.’”

Ann Zielke, parent, on her conversation with the board vice president.

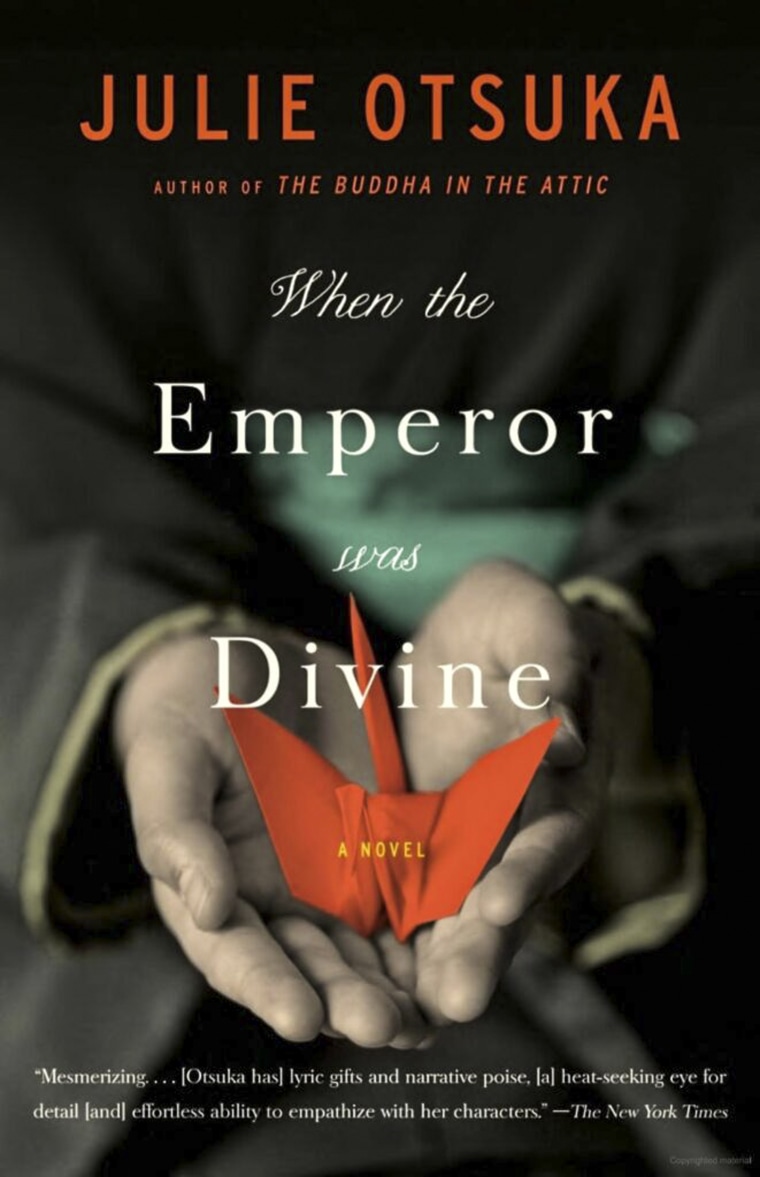

As of Thursday, almost 200 parents, alums, community members and staff of the Waukesha County district have signed a petition demanding the committee reconsider Julie Otsuka’s book — “When the Emperor Was Divine” — which was not moved forward during the early stages of the approval process June 13.

Board members also reportedly said that a book cannot be chosen for the sake of adding diversity to the curriculum, said the parents, who spoke with board members and attended the school board meeting earlier this month.

Ann Zielke, a parent in the district who kept a detailed log of her interactions with board members and shared them for this article, said that discussions around the book began months ago, after the district’s curriculum planning committee approved the novel in April. The book was subsequently sent to a group made up of three board members who approve educational materials before they’re purchased by the school board known as the educational services committee. Rather than move forward with the book, the committee — which is currently made up of School Board Vice President Terri Boyer, Treasurer Tracy Blair and member Laurie Kontney — requested more time for review, the parents said.

Zielke said she reached out to two board members for its rationale and eventually had a conversation the next month with Boyer, who sits on the committee. In the exchange, Boyer said that the addition of the book — alongside the class’ existing inclusion of “Farewell to Manzanar,” a separate memoir about Japanese American incarceration during WWII — to the curriculum created an “unbalanced” account of history, Zielke recounted.

Zielke said she was told, “We can’t just provide one side or the other side,” before the parent pressed Boyer on the issue, demanding the board member clarify her definition of “other.”

“What she said to me was that we actually need an ‘American’ perspective,’” said Zielke, who said she pointed out that those incarcerated were in fact Americans, before the conversation grew increasingly heated.

“She clarified and said that she felt that we needed the perspective of the American government, and why Japanese internment happened. And so then again, we had raised voices at this point. I told her specifically, I said, ‘The other side is racism.’”

Boyer said in an email the book was not approved due to “concerns in our process, not the content of the book.” She wrote in a follow-up email that district policy states the selection of instructional materials “shall not discriminate on the basis of any characteristics protected under State or Federal law.” and that “concerns were raised about whether the policy was followed.”

“To ensure the policy is followed, staff pulled the book from being recommended and will start the process over to ensure a fair and non-discriminatory process will be used to select a book for this class.”

The historical fiction novel, published in 2002, is loosely based on the lives of author Otsuka’s own family. It follows the experiences of a Japanese American family from Berkeley, California, who leave their lives behind after the U.S. government forcibly imprisons them in a camp in Utah during WWII, when anyone of Japanese descent was deemed a national security threats after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.

Zielke said Boyer told her she received a tip that the book was chosen on the basis that it was written by a nonwhite author. When Zielke asked if Asian students in the district deserve to see themselves in the curriculum, she said Boyer responded, saying, “they can go to the library and check out any books they want.”

School Board President Christopher Buckmaster also brought up concerns around balance in a separate call with Zielke, she said. When asked to clarify what kind of balance Buckmaster sought, he recommended the students read about the Rape of Nanjing, Zielke said. In the tragedy during the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Japanese military raped at least 20,000 women and girls, and killed 150,000 male “war prisoners” and 50,000 male civilians in the Chinese city of Nanjing. Buckmaster did not respond to a request for comment.

Brett Hyde, another board member, told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that he sensed board members felt that the perspective presented in Otsuka’s novel too closely mirrored that of “Farewell to Manzanar,” and suggested material related to the bombing of Pearl Harbor to provide “some history as to why the citizens of Japanese descent were viewed as a threat and what was the reasoning to have them put into the internment camps.”

Another board member, Kevin Zimmerman, said in an email that he did not believe anyone on the board had concerns regarding balance.

Records of the June meetings that featured discussions and arguments around the book are not available.

Minutes from an educational services meeting, which took place June 13, have not been shared to the school board website, where the records are generally posted. When a copy was requested, Boyer replied in an email that the minutes have not been approved. A board meeting took place later that same day.

When Zielke submitted an open records request for the video, Assistant Superintendent Jeff Petersen replied in an email, seen by NBC News, that the portion of the video that was removed was “unrelated to the official business of the meeting.”

Exchanges between board members and parents over the book took place before the meeting actually started. The discussion is not featured in the latest version of the video, which saw seven minutes of footage cut, Zielke said.

The district’s YouTube channel livestreams its board meetings, but Zielke, who repeatedly checked the page herself, said that the recording was uploaded, then deleted June 14. The video of the meeting reappeared later that day, with the seven minutes removed, she said.

“In response to your records request, the District’s technology personnel made efforts to determine whether the deleted portion of the recording was recoverable, and they have concluded that it is not,” he wrote. “As a result, there are no records responsive to your request.”

Neither Petersen nor Boyer responded to requests for comment on the altered video.

At the June 13 committee meeting in which it decided against moving forward with the book, the members reportedly provided no rationale, both Zielke and another parent in the district, Allison Hapeman, said.

“The dozen parents and alumni and students who showed up to that meeting just started yelling questions, because they were ready to gavel it out with zero explanation,” Zielke said.

Buckmaster confirmed the book was brought to the committee, but never moved forward to the full board. But he wrote that “at no point was this book banned or denied by the committee of the board or the full board.”

“Rather, district staff recommended that it be sent through the staff committee process again,” he wrote.

However, Zielke said, in both private and public conversations, board members were clear in their disapproval of the book and did not indicate the novel would be sent through the process for another review. In a June 10 email from Boyer to Zielke, seen by NBC News, the board vice president wrote, “not approving a piece of curriculum should not erase the other 99% we do approve.”

“The board is now saying that the district staff recommended the book come back but that was not made clear to anyone at that ESC meeting,” Zielke said. “I walked away knowing the committee didn’t approve something having to do with ‘diversity.’ … It feels like a backpedaling reason to explain this.”

Hapeman confirmed that when pressed by parents, the board members brought up similar arguments that were previously presented to Zielke. She said that the committee took particular issue with how the book was chosen to bring a diverse perspective into the curriculum.

The committee’s comments “pointed to their understanding or their belief that the fact that this book came from a diverse perspective meant that the committee that chose it was discriminating against white people.”

Allison Hapeman, parent

“At one point, Terri Boyer, in the meeting, did say, ‘How would you feel if they were only allowed to choose books by white people?’” Hapeman said.

Hapeman said that while many parents attempted to air their concerns, they were cut off.

“They get to have final say in who they will listen to. We were at the meeting that we are supposed to be able to speak,” Hapeman said. “But we were gaveled out while we were still speaking.”

Hapeman added that the committee’s comments in the meeting “pointed to their understanding or their belief that the fact that this book came from a diverse perspective meant that the committee that chose it was discriminating against white people.”

“They didn’t use that language, but everything pointed to that,” she said.

At the board meeting later that day, tensions grew and both parents said that they were not given a fair opportunity for a true exchange with the board. When one alum expressed the desire to speak before the meeting officially began, Zielke said an argument ensued.

Zielke said she has yet to hear from any parents who object to the book, and Hapeman added that the parents who’ve shown up to meetings have only supported its inclusion in the curriculum.

“I’m looking for my children to get an education that prepares them to live in the wider world … And that’s what I believe that public education needs to provide to all our students,” Hapeman said. “We’ll be in the district for many years to come here and I want my kids to be prepared for the life that comes next. And if these are the kinds of decisions that are continuing to be made, by narrowing the perspectives that they’re taught, then they won’t be prepared.”

The Muskego-Norway School District’s decision has drawn ire from the Japanese American community as well. David Inoue, executive director of the Japanese American Citizens League, sent the school board a letter earlier this month, demanding it reconsider the book’s use in the curriculum, particularly given the alleged arguments from board members.

“In the case of the Japanese American incarceration, the United State government has formally apologized to the Japanese Americans who were incarcerated, admitting our actions as a nation were constitutionally and morally wrong,” he wrote. “The story of what happened to the Japanese American community is an American story, one that balances the challenges of injustice, but also the patriotic stories of service and resistance. If anything, these are stories that need to be told more in our schools.”

“It is the absolute definition of racism to try and exclude something because it is a minority perspective,”

David Inoue, Japanese American citizen’s league.

Inoue called the school board’s concerns around the book choice being potentially discriminatory “ridiculous.”

“It is the absolute definition of racism to try and exclude something because it is a minority perspective,” Inoue told NBC News.

Otsuka also expressed disappointment in the school district, telling NBC Asian America that in the two decades since the book was published, the material has never been the source of debate in schools. She said that it’s critical for schools to lift up the perspective of marginalized communities, like Japanese Americans, whose stories have predominantly been framed through a white lens. Over the years, she said she’s heard from numerous high school readers about how her book served as their first introduction to the subject of the forced incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

“For so long, history has been presented in a very one sided way. It’s been written by mostly white men and it historically has been about white men,” Otsuka said. “A revisitation of history. And just, you know, I think, from the perspective of people who might have been left out of the official account is long overdue.

Otsuka added that reading stories from a diversity of communities is a “radical act of empathy” and can only serve to benefit all students.

“By reading, it collapses all distance between yourself and the other. You enter into their story,” she said. “It’s how we learn to be more compassionate human beings — by reading about people who are different from us.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com