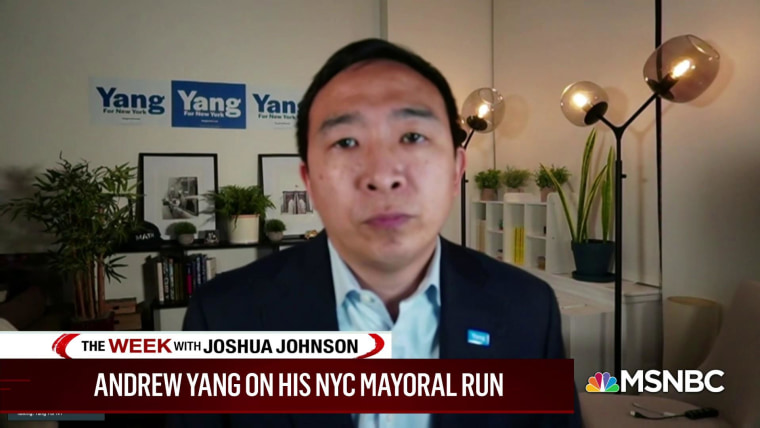

With less than two months to go before New York City’s Democratic mayoral primary, it appears that Andrew Yang’s fresh-faced, gee-whiz optimism really could push him over the top. Polling consistently shows that Yang, the onetime test prep executive, tech cheerleader and failed presidential hopeful, has become the candidate to beat. He has risen to the top of a crowded field with a distinctive campaigning style the city hasn’t seen in a lifetime: Yang radiates fun, enthusiasm and hunger for a post-pandemic, post-Bill de Blasio future. He’s literally talking about a “summer of love” in New York City. Casting himself as the consummate non-politician, Yang promises the city both forward-looking direction and a clean break with its past.

Casting himself as the consummate non-politician, Yang promises the city both forward-looking direction and a clean break with its past.

But Yang’s promise of a brave new city is more style than substance. His actual ideas about how the city should work reveal some very old-fashioned, even sclerotic thinking. And Yang has aligned himself with some of the most entrenched interests in the city. Rather than reckon with the cascading crises hitting New York City — or the opportunities they might present to a truly forward-thinking politician — Yang seems to want to move backward. Fundamentally, Yang champions the same business-class neoliberalism that has reigned since the 1975 fiscal crisis. This is frustrating given that New Yorkers actually have a chance to push our political, social and economic order into the 21st century.

In tweets, speeches and policy proposals, Yang says over and over that he wants to bring New York “back.” What exactly does that mean? Often the sentiment is unobjectionable, if banal: Who doesn’t desperately miss IRL entertainment or dating? Of course, should the swift vaccine rollout continue apace, many of those cherished aspects of cultural and social life may have returned by the time the next mayor takes office in 2022.

In more substantive ways, Yang’s drive to bring back pre-pandemic New York could be regressive. Take his increasingly vocal hostility to remote work. In meetings with members of the city’s so-called permanent government of business leaders, Yang has suggested that the city offer financial incentives to commuters who live outside the city to return to big Midtown offices. Yang has clearly signaled that he wants to restart the same central business district development machine that has driven the city for a lifetime by catering to large corporations and commercial real estate interests.

But the pandemic may have broken the old economic model — and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Polls consistently show that enormous majorities of Americans enjoy working from home at least part of the week. New York City employers expect that more than half of formerly full-time in-person workers will stay at least partly remote. As large companies like JPMorgan Chase shrink their physical footprints, commercial rents and real estate valuations have cratered. Falling rents scare landlords, but they present opportunities for smaller companies and retailers who previously couldn’t afford to compete for space in Manhattan with multinationals that lease multiple floors of football field-size open plan offices.

The pandemic may have broken the old economic model — and that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

At least some unused office space could be converted into desperately needed housing. By cooling off the central Manhattan real estate market, remote work could reduce the cost of living throughout the city, which was shrinking the population even before the pandemic. Converting offices to residences might lower rents and thus local tax revenue. But if the city can retain pre-pandemic levels of white-collar employment only by paying companies and commuters so much that the subsidies outweigh the savings of slashing office space by half, it’s not clear that it makes more fiscal sense than accepting and adapting to new ways of working.

At the same event where he suggested paying Short Hills residents to come to Midtown, Yang told PR heir Steven Rubenstein that taxes on the rich threatened New York’s “value proposition.” He trotted out the familiar threat that if politicians raise taxes, the rich will “vote with their feet … and head to Florida.” That puts him at odds with the rising progressive tide in New York politics: Democrats just used their new veto-proof majorities in the state Legislature to raise taxes on millionaires and corporations after a decade of obstruction by Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

But contrary to Yang’s talking points, research shows that the rich don’t flee local tax hikes. In fact, they cluster in high-tax, high-service jurisdictions just like New York, where they can get better government, tap into deeper networks, recruit top talent and enjoy world-class amenities. For instance, after New Jersey and California introduced millionaire’s taxes in 2004, the number of super-rich residents in those states increased. Indeed, many plutocrats who fled New York at the beginning of lockdown before the tax hike are coming back. Nonetheless, Yang knew what long-established power brokers wanted to hear.

Yang’s old-fashioned economic and political instincts showed themselves again when he said the city should save its federal stimulus windfall for a rainy day. Like so many pro-business critics of de Blasio, Yang hit the current mayor for expanding the city’s payroll by 30,000 new positions over his tenure. As he told the Daily News, “It’s not clear that all these additional hires are on the front lines doing things that are going to help accelerate our recovery.”

Yang’s call for austerity, which aligns with the philosophies of fiscal conservatives like the Citizens Budget Committee, is harmful and thoughtless. De Blasio expanded the city’s payroll by hiring exactly the kinds of workers who will be on the front lines of the effort to get New York running again: teachers (including those hired under his truly progressive universal pre-K program, the clear inspiration for the Biden administration’s national proposal), first responders and medical professionals. Does Yang want to fire teachers? Does he think the city needs fewer doctors and nurses in public hospitals right now?

Politically, Yang also seems to augur a step backward. His senior campaign staff members are all employees of a lobbying firm founded by two former aides to former Mayor Mike Bloomberg. Yang hasn’t explained how he would prevent conflicts of interest should he take office. Meanwhile, the Machiavellian Democratic operative Lis Smith has taken charge of Yang’s outside fundraising. Smith’s biggest contribution to New York politics to date was working as a spokesperson and strategist for the Independent Democratic Conference, a breakaway group of Democratic state senators who for years helped ensure Republican control of the chamber. Yang also campaigned with the most right-wing candidate for Manhattan district attorney. He sought and got the endorsement of South Brooklyn’s New Era Democrats, a political club that endorsed Republican Rudy Giuliani twice over David Dinkins, the city’s first Black mayor.

Even some of Yang’s more idiosyncratic proposals rest on conservative ground.

Even some of Yang’s more idiosyncratic proposals rest on conservative ground. Adapting his signature presidential platform issue to his mayoral run, Yang wants to give a “basic income” of $2,000 a year to New York’s poorest residents. The city would pay for the first billion dollars — but anything more would come from philanthropic sources, conditioning expansion of the city’s welfare state on billionaires’ largesse and likely muffling criticism of the ultra-rich.

He wants to transform the city into a “hub” for Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. What this means isn’t exactly clear — would he have the city accept tax payments in the wildly fluctuating currencies? Does he want to turn North Brother Island into a BTC mining rig? — but Bitcoin isn’t the futuristic money it may superficially appear to be; it’s just a speculative financial asset with a special appeal to the 21st century equivalent of gold bugs.

If he wins, Yang will indeed bring back a lot of New York’s pre-pandemic dynamics: supplication to billionaires, corporations and landlords; the commuting rat race; and a political class that consistently works to thwart progressives in what should be their biggest stronghold. New Yorkers should leave that world behind.

We have a rare opportunity to chart a new path. The pandemic revealed how vulnerable decades of neoliberal governance had left the city and the country. It has also presented the biggest opening for activist government since the President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. A likely post-vaccine economic boom could power even more public investment. The Democratic supermajority in the Legislature, with its many young progressives, could help New York City fight power brokers who have constrained the metropolis’ political horizons for decades. But for all his talk of tapping into the zeitgeist and offering a new kind of mayoral campaign, Yang doesn’t seem to want to meet the moment.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com