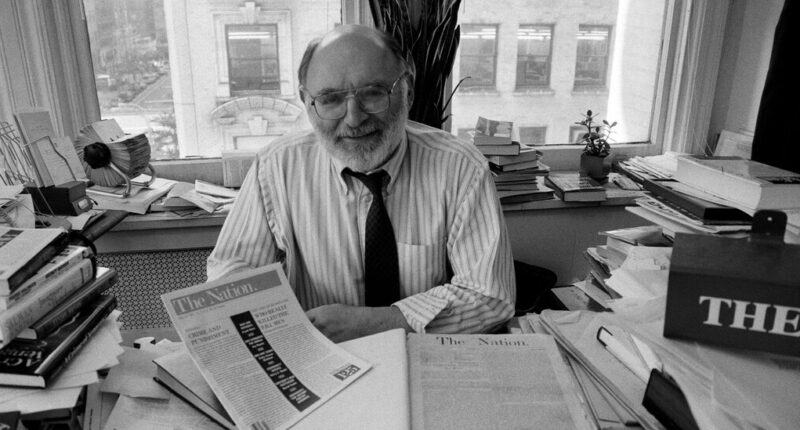

Victor S. Navasky, a witty and contrarian journalist who for 27 years as either editor or publisher commanded The Nation, the left-leaning magazine that is America’s oldest weekly, and who also wrote the book “Naming Names,” a breakthrough chronicle of the Hollywood blacklisting era, died on Monday in Manhattan. He was 90.

His death, in a hospital, was caused by pneumonia, his son, Bruno, said. Mr. Navasky had homes on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and in Hillsdale, N.Y.

The Nation, based in New York, was founded in 1865 by abolitionists and had long been an influential voice for civil rights, free expression, progressive labor legislation and criticism of the Vietnam War. When he was named editor in 1978, Mr. Navasky introduced a droll sensibility that leavened the magazine’s sometimes too-earnest prose.

In addition to adopting an irreverent tone in his own articles, he encouraged idiosyncratic writers like Alexander Cockburn, Christopher Hitchens and Calvin Trillin, who in his “Uncivil Liberties” column referred to his boss as “the wily and parsimonious Victor S. Navasky.”

Mr. Navasky also provided a forum for feminist voices, like those of Katha Pollitt and Katrina vanden Heuvel, who succeeded him as editor in 1995 when he led a group of investors in buying the magazine and became its publisher. He stepped down as publisher in 2005, succeeded by Ms. vanden Heuvel.

Mr. Navasky offered a sense of his editorial approach in an interview with The Brooklyn Rail in 2002.

“I think it was Walter Cronkite who used to end his nightly newscasts by saying, ‘That’s the way it is.’ Well, I wanted to put out a magazine which would say: ‘That’s not the way it is at all. Let’s take another look.’”

Circulation rose from 20,000 when Mr. Navasky took the editorial helm to 132,000, not including 15,000 online subscriptions, in 2019, when Ms. vanden Heuvel stepped down as editor (though she remained the publisher). But such numbers understate the magazine’s influence on liberal policymakers — academics, pundits, progressive activists, government officials and congressional staff members — people who were “interested in ideas,” as Mr. Navasky said.

He was known for his ardent steadiness as a Cold War warrior. He wrote pieces defending Alger Hiss, a high State Department official in the 1930s, against charges that he had been a Soviet spy, and assailing the government’s handling of the prosecution and sentencing of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were also charged with spying for the Soviets and were executed.

As new revelations over the decades seemed to back up charges in both cases, Mr. Navasky questioned the reliability of the evidence, and at his death the guilt of Alger Hiss and, at least, Ethel Rosenberg was still open to question.

Mr. Navasky’s wry iconoclasm started early. While at Yale Law School, he and a friend founded a satirical magazine, Monocle, and a few years later tried to make a go of publishing it in New York City as a free-standing “leisurely quarterly,” which Mr. Navasky said meant it came out twice a year.

An early edition gave readers a taste of its approach to humor. It featured a version of the Gettysburg address as orated by the president at the time, Dwight D. Eisenhower. It began: “I haven’t checked these figures yet, but 87 years ago, I think it was …”

Distributed by Simon and Schuster, the magazine treaded water for half a decade, drawing such writers as Nora Ephron, Sidney Zion, C.D.B. Bryan, Ralph Nader, Dan Greenburg and Marvin Kitman. During the 1963 newspaper strike in New York City, Monocle put out parody issues of The New York Post and The Daily News, called The Pest and The Daily Noose.

Monocle made an occasional big splash with its publication of the book “Report From Iron Mountain: On the Possibility and Desirability of Peace” (1966), a satire of think-tank think by Leonard Lewin. Predicting that the American economy would collapse if preparations for war should end, the book was taken seriously by many despite statements by its creators that it was a hoax; its afterlife among conspiracy theorists continues.

For a time after Monocle’s demise, Mr. Navasky turned to writing well-reported and thoughtful, often provocative magazine articles. For The New York Times Magazine, he profiled Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, former Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas and the defense lawyer William Kunstler.

Several of his pieces had a Monocle-like bemusement to them, like his portrait of the clubby world of New York intellectuals, even if by some measures he would have fit right in.

“That you may never have heard of a majority of these people is not surprising,” he wrote, “because members of this establishment traditionally talk only to each other and publish in journals which are prepared primarily for each other’s consumption.”

Mr. Navasky went on to publish two widely praised works of history. The columnist Joseph Kraft called Mr. Navasky’s “Kennedy Justice,” a 1971 study of the Justice Department under Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, “probably the best book ever done on the workings of a great department of American government.”

Almost a decade later, Mr. Navasky published “Naming Names” (1980), considered by many the definitive account of the Hollywood blacklisting era. The book focused on the ex-Communist writers, directors and producers who testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee and chose to inform on colleagues.

Critics praised the book for its fairness and its compassion for people grappling with wrenching choices. However, some conservative critics said it was more inclined to denigrate the so-called informers, like the novelist Budd Schulberg and the director Elia Kazan, whose tortured explanations for their decisions Mr. Navasky found illogical.

“His sympathies are clearly with those who refused to name names,” Richard Sennett wrote in The New York Times Book Review. “But he refuses to prejudge the informers, to treat them simply as cowards or monsters.”

The book received the National Book Award in 1982 for general nonfiction-paperback.

Victor Saul Navasky was born on July 5, 1932, on the Upper West Side, the second child of Macy and Esther (Goldberg) Navasky. His father was the part owner of a clothing manufacturing business, and his mother was her husband’s secretary and bookkeeper.

Victor attended the Rudolph Steiner School, then the Little Red Schoolhouse and Elizabeth Irwin High School in Greenwich Village, both popular with families on the bohemian left. He received a bachelor’s degree in 1954 from Swarthmore College and served two years in the Army, working as a medic outside Anchorage and writing for and editing his regimental newsletter. Afterward, he attended Yale Law School on the G.I. Bill, graduating in 1959.

He married Annie Strongin, a stockbroker, in 1966. In addition to his son, she survives him, along with two daughters, Miri and Jenny Navasky, and five grandchildren.

Mr. Navasky joined The Times in 1970 as a manuscript editor and staff writer for The Times Magazine and was a frequent book reviewer. His admiring review of a collection of articles by The New Yorker writer and editor Roger Angell was written in the “we” voice then used then for some of the magazine’s chatty Talk of the Town pieces. It closed with a line about “a lady we know” who would be delighted with a gift of the book and is “fully capable of debating how many Angells can dance on the head of a pin.”

Shortly before he left the paper in 1972, Mr. Navasky began writing “In Cold Print,” a monthly column on the publishing world for The Times Book Review. It appeared until 1976.

He took an uncharacteristic career detour in 1974, managing the quixotic Democratic campaign of former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark to unseat New York’s popular Sen. Jacob K. Javits, a Republican. When Mr. Navasky volunteered that he had no experience in this kind of work, Mr. Clark responded, “That makes two of us.’’

Mr. Clark was candid to a fault, endorsing the creation of a Palestinian state in “co-union with Jordan” at a time when that position would cost him Jewish voters, and defending a trip he took to Hanoi, the North Vietnamese capital, at the height of the Vietnam War. Mr. Navasky did not try to dissuade him from taking such positions, and Senator Javits won handily despite an anti-Republican tide that year spurred by the Watergate scandal.

After stepping down in 2005 to become The Nation’s publisher emeritus, Mr. Navasky taught magazine writing and editing at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, directed its George T. Delacorte Center for Magazine Journalism and chaired The Columbia Journalism Review. The last position drew complaints from conservative media that he was a partisan holding a leadership position with a watchdog journal that was supposed to impartially assess the quality and ethics of newspapers, magazines and other media.

Mr. Navasky applied his leftist outlook in at least one corner of his personal life — his vacation home, in Hillsdale, in Columbia County near the Connecticut border. In 1971, he, a friend and their wives purchased a 130-acre property there that they divvied up among 13 people and their families — including a painter, a poet, a violinist, an astrophysicist, an N.A.A.C.P. lawyer, a psychotherapist and several writers.

It seemed to a Times reporter describing the arrangement in a 2009 article the equivalent of a 1960s commune, minus the drugs and group sex. Ever the independent thinker, Mr. Navasky rejected that description.

“Really,” he said, “it’s more of a middle-class convenience than a ’60s commune.” It was also, he added, “weirdly nonpolitical.”

Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, a longtime book critic for The Times who died in 2018, and Alex Traub contributed reporting.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nytimes.com