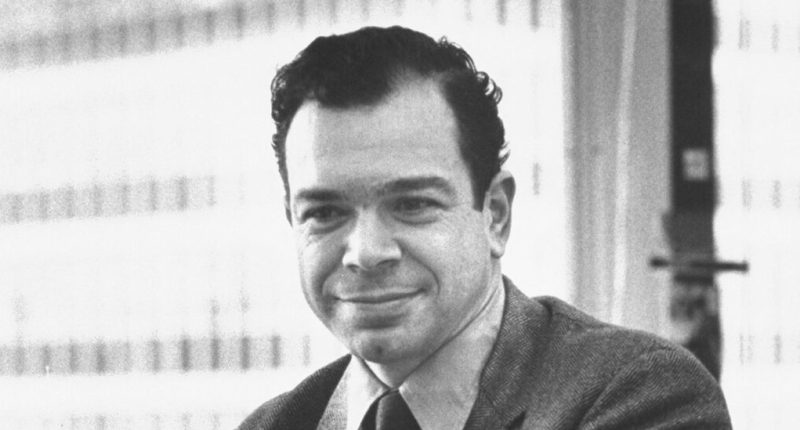

Ted Morgan, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and prolific author of acclaimed nonfiction books who renounced his noble French title in favor of a conventional all-American name, died on Wednesday in a nursing home in Manhattan. He was 91.

The cause was complications of dementia, his daughter, Amber de Gramont, said.

As he straddled two cultures, Mr. Morgan experienced enough adventures for two lifetimes, including a half-dozen wars, near death from thirst while crossing the Sahara, and waterfront saloon brawls. Many of these ordeals found their way into his journalism and a score of books, as did more intellectually exciting episodes.

Whether writing under his aristocratic French name, Sanche de Gramont, or his adopted American one — “Ted Morgan” is an anagram of “de Gramont” — Mr. Morgan covered topics as varied as opera, advertising, the police, Nazi war criminals, laid-back California living, the legal aspects of pornography, and politics, both in the United States and abroad.

As he demonstrated in biographies of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, Mr. Morgan did not hesitate to tackle subjects that had already been plumbed by authors with more scholarly credentials. But few writers could assemble dry facts and telling details with more gusto and brio.

Recounting the oft-told story of young Churchill’s bold flight from a prison camp during the Boer War for his book “Churchill: Young Man in a Hurry 1874-1915,” published in 1982, Mr. Morgan pointed out that the escape plan was devised by two of Churchill’s fellow prisoners, whom he left behind.

“One is tempted to say that it would have been hard to mess up one of the more dramatic careers of the 20th century,” Christopher Lehmann-Haupt wrote in a New York Times review. “But a life so full could easily have meandered into tedium, and this almost never happens in Mr. Morgan’s treatment.” The book was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize.

In his 1978 autobiography, “On Becoming American,” Mr. Morgan wrote about his New World conversion and flaunted his own foibles and biases. “Much more than my name has changed,” he wrote. By taking up American citizenship, he claimed to have shed his European elitism for egalitarian principles. He now shared housework with his wife and became more permissive with his children, he wrote. Ted Morgan preferred McDonald’s hamburgers and California wines to Sanche de Gramont’s coq au vin and French vintages.

Mr. Morgan conceded that his new compatriots could be provincial, bigoted and crassly materialistic. But he also recognized their generosity, openness and willingness to take risks. “Anxiety is the price that must be paid for boundless opportunity,” he concluded. “And not everyone can handle it.”

Ted Morgan was born Sanche Charles Armand Gabriel de Gramont in Geneva on March 30, 1932. He was the descendant of hereditary French dukes and counts going back three centuries. His father, Count Gabriel Antoine Armand de Gramont, had moved temporarily from Paris and sold luxurious Bugatti automobiles in Geneva while preparing for his entrance exams for the French diplomatic service. His mother, Mariette Negroponte, was born in Greece. He had two younger brothers, George and Patrick.

In 1937, the family moved to Washington, where his father was an official at the French embassy. Two years later, on the eve of World War II, they returned to Paris. When France fell to the Nazis in 1940, the count sent his family back to the United States by way of Spain and Portugal, while he escaped to Britain and joined the Royal Air Force. After a number of bombing missions over Germany, he was killed in a crash landing during a training flight in 1943.

Sanche de Gramont, who inherited his father’s title, grew up between American and French identities. He dropped out of the Sorbonne in Paris and finished his university studies at Yale in the 1950s. It was the height of the Cold War abroad and McCarthyism at home. The C.I.A. and the Dow Chemical Company vied to recruit the smartest Yale seniors.

“I was part of an undergraduate body that became known as the silent generation,” Mr. Morgan wrote in his autobiography. “We wore J. Press sports jackets, button-down shirts, ties with regimental stripes and white buckskin shoes.” Uninterested in political protests, he and his fellow students confined their acts of youthful rebellion to scaling landmark buildings at night — first, the Yale towers, then the George Washington Bridge and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan.

Drafted by the French Army in 1955, the young count spent most of his two-year stint in the Algerian war for independence as a lieutenant in a combat regiment and the remainder as a propaganda officer. In “My Battle of Algiers” (2006), he recounted atrocities, some of which he witnessed, committed by both sides.

Returning to the United States, he was a reporter for The Worcester Telegram, a local newspaper in Massachusetts, and worked for The Associated Press before joining The New York Herald Tribune.

His breakthrough moment came on the night of March 4, 1960, while he was working the late shift on the rewrite desk of The Herald Tribune. A call from an editor alerted him that Leonard Warren, a celebrated baritone, had just died during a performance of Verdi’s “La Forza del Destino” at the Metropolitan Opera. Mr. Morgan, who at the time was still writing as Sanche de Gramont, rushed to the opera house and quickly pieced together a detailed account of the death.

Mr. Warren, in the role of Don Carlo, had collapsed onstage after singing the aria “Urna fatale del mio destino” (“Fatal urn of my destiny”). “There was an awesome moment as the singer fell,” Mr. de Gramont wrote, on deadline. “The rest of the cast remained paralyzed. Finally someone in the capacity audience called out, ‘For God’s sake, bring down the curtain!’”

His coverage earned Mr. de Gramont the Pulitzer Prize for local reporting.

In the ensuing years, he energetically pursued a wide range of interests, both as a journalist and as the author of books about France and Africa. He often reported from Africa in the 1960s, and he was severely wounded while covering the civil wars in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. After French diplomats ignored his plight, he was transported to a hospital thanks to the intervention of the American consul. He later said that the episode had strongly disposed him in favor of becoming a U.S. citizen.

Of the three books on France he wrote as Sanche de Gramont, the most widely read was “The French: Portrait of a People.” Published in 1969, it was praised by some critics but panned in The New York Times Book Review by John L. Hess, a Paris-based Times correspondent, for what he called its overly harsh portrayal of his compatriots. “It does not omit a single unkind stereotype: France is ‘a country where avarice is a virtue’ and ‘adultery is the norm,’” Mr. Hess wrote.

Mr. de Gramont stopped using his French name in the 1970s. Friends and publishers warned him that he risked losing his established readership. But he joked that the only advantage of his titled name was that it helped him get reservations at expensive New York restaurants.

Even before becoming a U.S. citizen in 1977, Mr. Morgan twice wed American women. His first marriage, to Margaret Kinnicutt, ended in divorce in 1968. He and his second wife, the poet Nancy Ryan, had a son, Gabriel, and a daughter, Amber, before divorcing in 1980. Six years later he married Eileen Bresnahan.

In addition to his daughter and his son, Mr. Morgan, who lived on Manhattan’s West Side, is survived by his wife and four grandchildren.

His most critically lauded books were published under the name Ted Morgan. They included “FDR: A Biography” (1985), “Literary Outlaw: The Life and Times of William S. Burroughs” (1988) and “An Uncertain Hour: The French, the Germans, the Jews, the Barbie Trial, and the City of Lyon, 1940-1945” (1990).

“Maugham,” his 1980 biography of the British playwright and novelist W. Somerset Maugham, drew the special admiration of critics. In his Times review, Mr. Lehmann-Haupt wrote that Mr. Morgan “never fails to fetch your attention back with some marvelous detail,” adding that “one dare not skip a word of Mr. Morgan’s text.”

For all his literary and journalistic accomplishments, Mr. Morgan insisted that he preferred to be remembered most for having abandoned his Old World roots to assume a New World identity.

“I think,” he wrote, “I would want my gravestone to read: ‘Here lie the remains of Ted Morgan, who became an American.’”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nytimes.com