The prohibitive favorite to win the Republican presidential nomination looks to be on the verge of victory in Iowa and leads by wide margins in national polls and in other key states — except for one: New Hampshire, where one challenger has been gaining steam in recent polls, raising the possibility the Granite State may turn a coronation into a genuine competition.

If it sounds like a description of the current GOP proceedings, well, it is. But it was also the set-up more than two decades ago for a Republican primary season that could offer a useful lens through which to view the current race.

There are, obviously, glaring differences in tone and substance between George W. Bush and Donald Trump. But the trajectory of Bush’s candidacy in the lead-up to the 2000 primary season is practically identical to Trump’s this time around. The then-Texas governor spent 1999 building a staggering advantage in national polling, racking up endorsements and intimidating multiple rivals out of the race before the first votes were cast.

Trump’s 2023 proceeded similarly. In fact, Trump is the first nonincumbent Republican presidential candidate since Bush to enter an election year averaging over 50 percent support in national polling. And he’s also the first since Bush to enjoy an average lead of more than 20 points in Iowa this close to the caucuses.

In Bush’s case, he had little trouble living up to the hype in Iowa, winning 41 percent of the caucus vote — the highest share ever for a nonincumbent, and also a number that Trump has been surpassing in recent polling. Bush easily defeated his main threat in the state, Steve Forbes, by 11 points. Forbes, not unlike Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis currently, had practically staked his campaign on the Hawkeye State, tacking to the right with an emphasis on cultural issues. His caucus showing was respectable, but hardly the campaign-altering upset he’d been banking on. Forbes trucked on through New Hampshire, but he finished as an afterthought there before dropping out.

But Forbes had never been the candidate who worried the Bush team in New Hampshire. That was John McCain, who put up only a token effort in Iowa and made his stand in the Granite State. The Arizona senator presented himself as reform-minded political maverick, traversing the state on a campaign bus dubbed the “Straight Talk Express” and merrily fielding questions from all reporters on board with nothing off the record. Long before Iowa, McCain was already showing traction in New Hampshire polling, and even as Bush was celebrating his lead-off caucus victory, it was clear McCain was a threat to win New Hampshire.

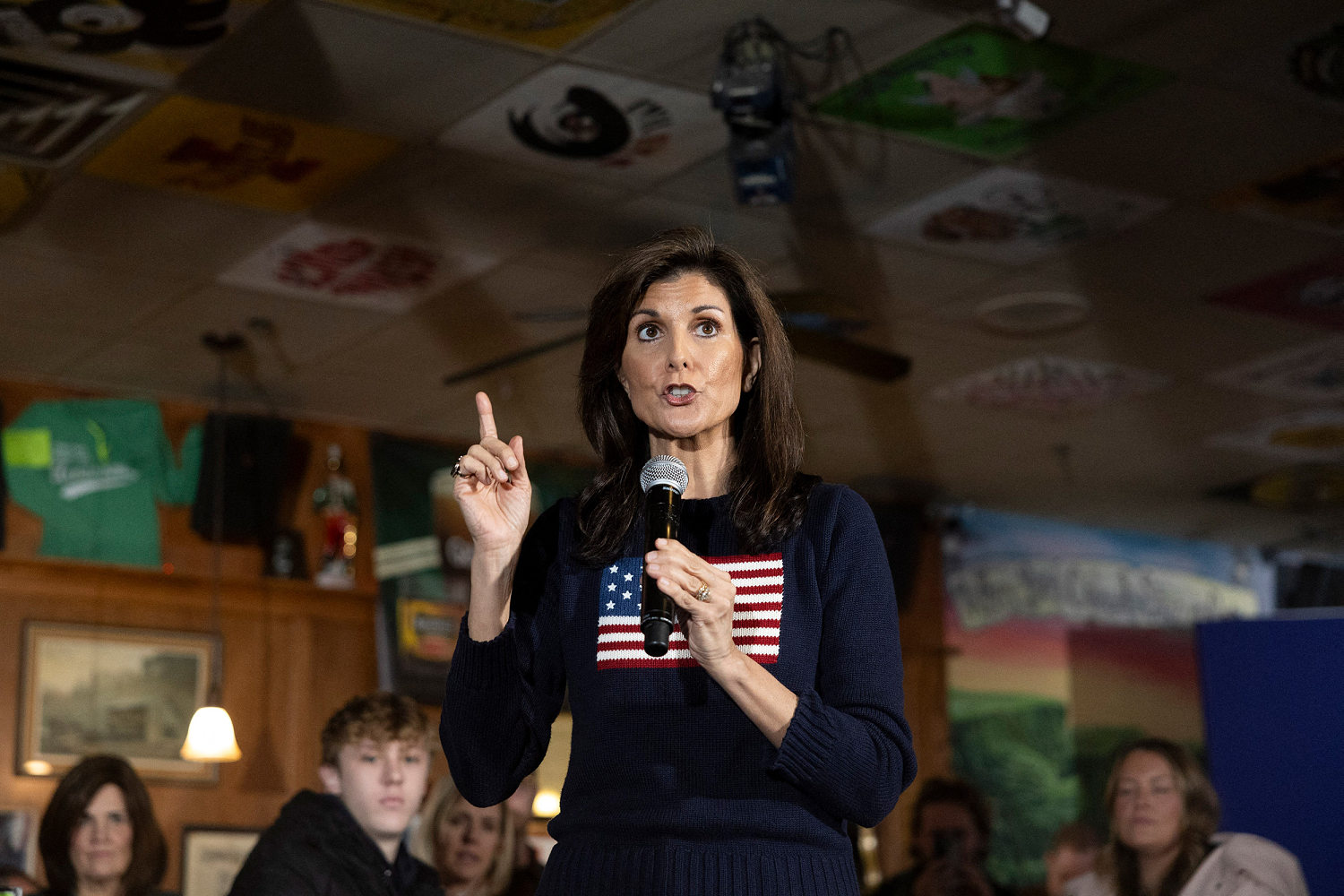

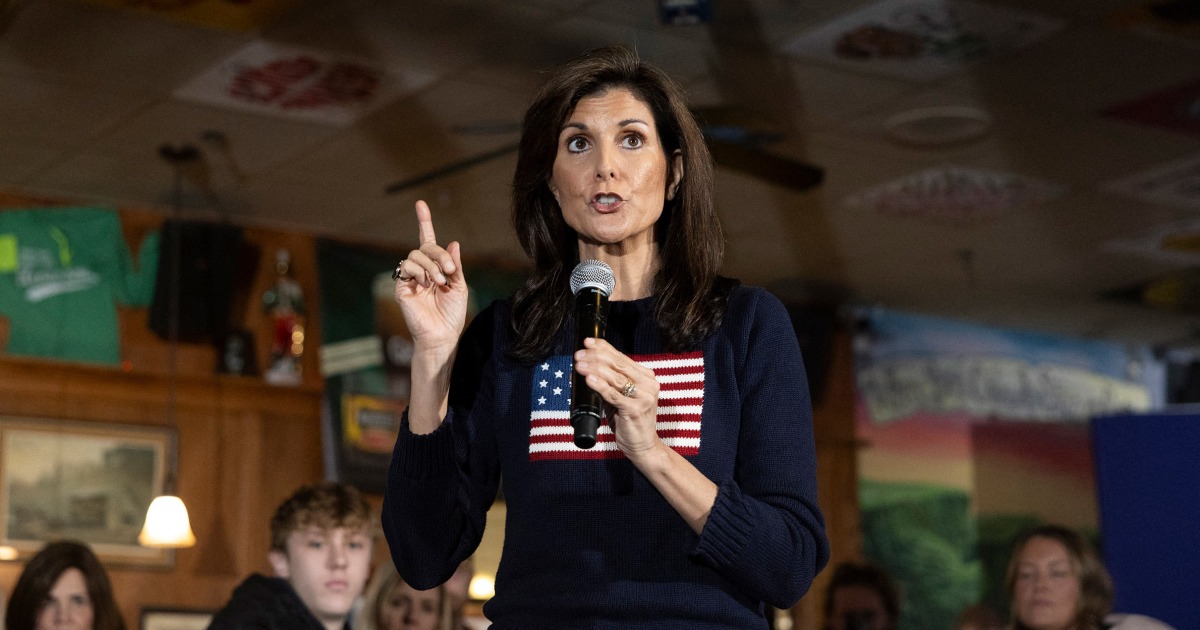

Here, the parallel between ’24 and ’00 is clear, with the role of McCain now being assumed by former United Nations Ambassador Nikki Haley.

While it’s true that she’s made more of a push in Iowa than McCain ever did, it’s also true that she’s also spent far less time there than DeSantis has — and she’s invested far more than the Florida governor has in New Hampshire. Haley herself seemed to nod to a New Hampshire-centric strategy last week when she told a Granite State crowd that, “You know how to do this. You know Iowa starts it. You know that you correct it.” (Haley later insisted to Iowans that she was joking.)

Like McCain, Haley has already gained traction in New Hampshire. Exactly how much is a matter of debate, with new polls showing a Trump lead of varying sizes. But whatever the exact margin, Haley looks poised to make Trump sweat in New Hampshire in a way he hasn’t so far in Iowa.

And, like McCain, she’s doing it by showing particular appeal to the state’s independent voters, who are not just permitted to vote in the Republican primary but who regularly flock to these contests in droves. Every recent poll in New Hampshire has shown Haley ahead of Trump among independent voters, getting about half of her total support from that group. She also fares well among those with college and post-graduate degrees, along with self-described moderates.

The resemblance between Haley’s budding New Hampshire coalition and McCain’s is uncanny. In McCain’s case, it translated into a political earthquake. On primary night in 2000, he didn’t just defeat Bush; he crushed him, 49% to 31%. The scale of the blowout surprised even Bush loyalists who had been pessimistic about the state. The exit poll told a dramatic story: Among independent voters, McCain clobbered Bush by 41 points, 60% to 19%. Among moderates, the spread was 36 points.

Instantly, the race for the GOP nomination was transformed. Using the newborn internet, McCain gobbled up millions in small dollar donations practically overnight. The McCain vs. Bush contest transfixed the media, which framed it as a David vs. Goliath battle and took on an editorial tone transparently sympathetic to McCain. The coronation, it appeared, had been interrupted, and now there would be a real fight — one that McCain just might win. This was the storyline that emerged.

The loyalty test phase of the primary

McCain likened his New Hampshire triumph to catching lightning in a bottle, precisely what Haley is now seeking in the state. In her case, it probably wouldn’t take a margin of nearly 20 points to accomplish it; any kind of victory over Trump would be a major jolt.

And if she does manage to succeed, attention will then shift, just as it did in 2000, to South Carolina — which is where everything went haywire for McCain in ’00, and where, if it comes to that, it could for Haley, too, even though South Carolina is her home state.

Much can and has been said and written about the 2000 South Carolina Republican primary. Suffice to say, it was ugly, most infamously because of allegations of an underground effort by Bush allies to smear McCain.

But fundamentally, it was the very seeds of McCain’s New Hampshire success that hurt him in the Palmetto State, where the GOP primary electorate is far more conservative.

Bush and his team turned to their advantage McCain’s appeal to independents, his fawning media coverage and the sudden enthusiasm for him from even some prominent Democrats. Bush framed the choice to South Carolina as a loyalty test. Were primary voters with the liberal media’s candidate, the one who was a big hit with non-Republicans and even some, as Bush called them, “mischievous” Democrats? Or were they Republican loyalists?

McCain countered by saying his appeal outside the GOP made him much more electable. And the polls backed him up: A CNN/USA Today survey showed Bush leading the presumed Democratic nominee, Vice President Al Gore, by 9 points — and McCain up by 22. (Similarly, polls currently show Haley outperforming Trump against Joe Biden, and she has made that part of her stump speech and advertising campaign.) At a 2000 rally, McCain declared: “I say to independents, Democrats, Libertarians, vegetarians: Come on over and vote for me!”

On primary night, the Bush argument prevailed, easily. And again, the exit poll told a vivid story. While there is no official party registration in South Carolina, voters who identified as independents went lopsidedly for McCain, as they did in New Hampshire. But they made up a far smaller share of the electorate.

Meanwhile, those who said they were Republicans sided with Bush by 41 points. Overall, nearly 80 percent of Bush’s voters were self-identified Republicans; for McCain, fewer than 40 percent were. And with that far different mix of Republicans and independents in the electorate compared to New Hampshire, Bush won South Carolina by 13 points, and McCain’s momentum halted.

The 2000 campaign would last a few more weeks, with McCain engineering another dramatic victory in Michigan. But by then, the dividing line was obvious. Michigan’s open primary rules allowed independents and Democrats to vote, and they made up just over half of the GOP electorate — providing McCain with just enough votes to carry the state. But this just reinforced Bush’s core message that his opponent was relying on the other team’s voters. After a disappointing Super Tuesday, McCain withdrew from the race, and the nomination was Bush’s.

If she is able to attain lift-off in New Hampshire, the McCain story offers an obvious cautionary note for Haley. A victory powered by non-Republicans (and no small number of Trump-hostile voters) would likely be viewed with suspicion by Republicans elsewhere. This would be especially true if Haley were to enjoy anything like the glowing media coverage McCain did 24 years ago.

The Republican Party has changed dramatically since 2000, but among its core voters, a strong element of loyalty remains; now, though, it’s less of a loyalty to the party itself and more of a loyalty to Trump. Trump could to challenge voters in South Carolina and beyond to the same basic test Bush did: Are you with me or are you with them? And just like in 2000, there aren’t many primaries and caucuses where the “them” side would be big enough to win.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com