The much-anticipated “Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks” hits bookstores — and the mailboxes of those wise enough to pre-order — on Tuesday. The 999-page volume includes entries from 1941, when Highsmith was a student at Barnard College, to 1995, the year of her death, and gives unprecedented access to one of the 20th century’s most notable and misanthropic writers.

The notebooks and diaries, consisting of 8,000 pages, were discovered after the author’s death by her longtime editor, Anna von Planta, who also edited the collection. It took years to translate and transcribe the handwritten entries, written in English, German, French, Spanish and Italian. But the task of producing a single, cohesive volume was equally as monumental — a labor that von Planta outlines in the introduction.

Entries from the 56 notebooks and diaries, which served different purposes for Highsmith, were interwoven so that “when read in tandem they help to gain a holistic understanding — in Pat’s own words — of an author who concealed the personal sources of her material for her entire life, and whose novels are more likely to distract us from who she was, than lead us to her,” von Planta writes.

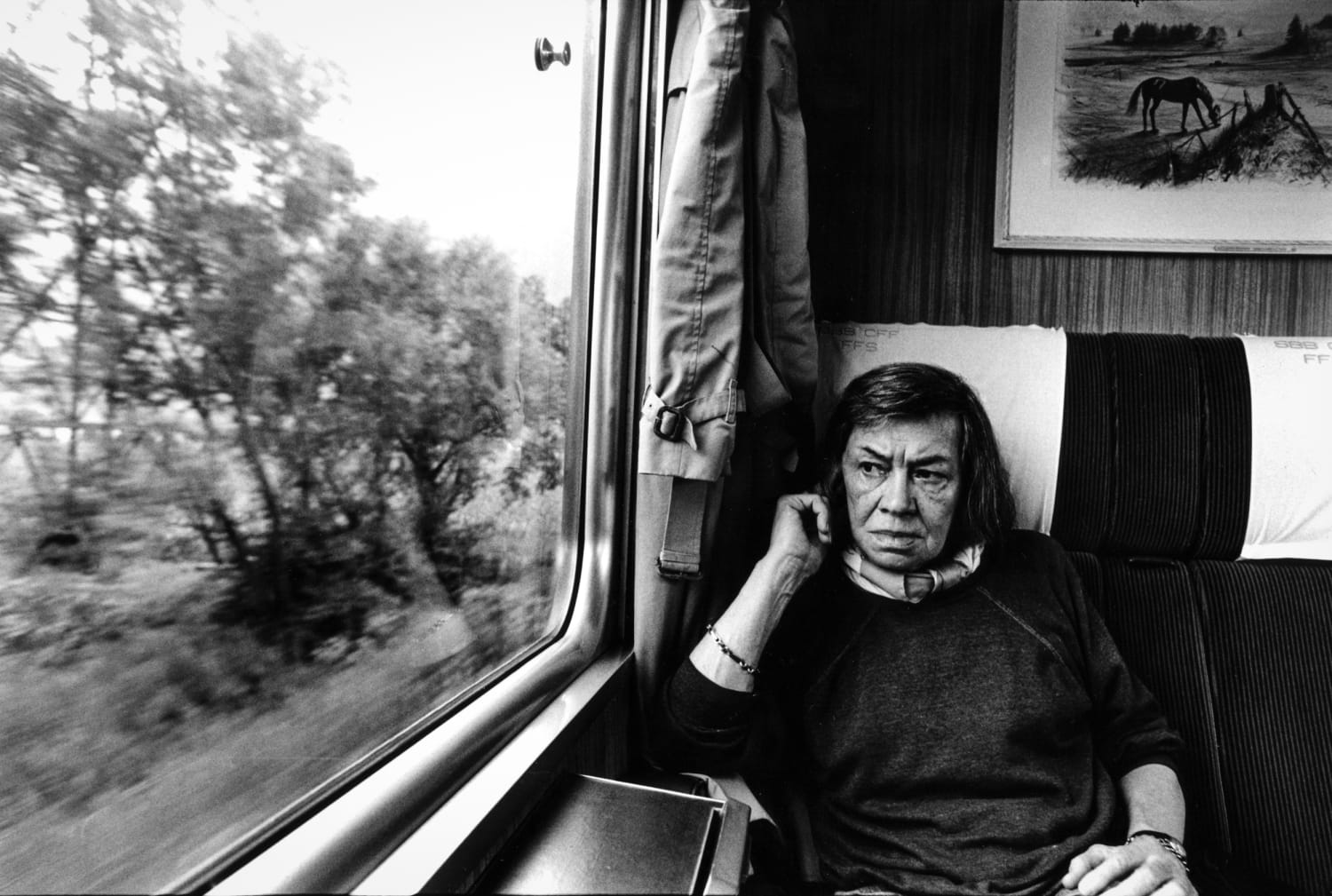

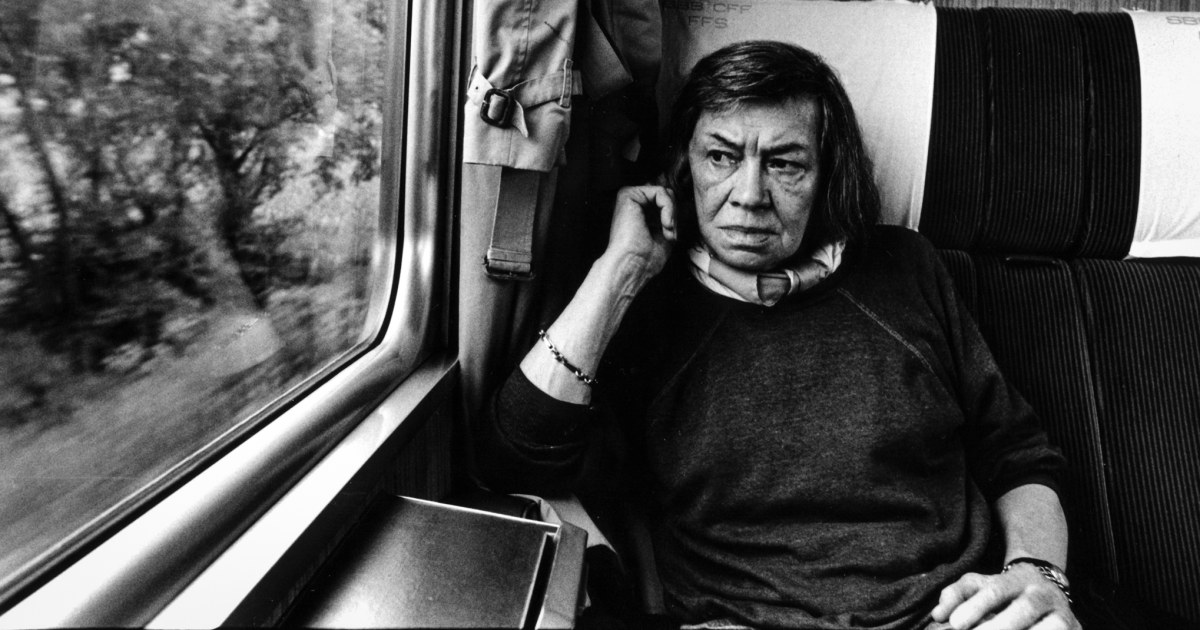

The author of popular, cerebral thrillers like “Strangers on a Train” and “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” Highsmith cultivated the mystique of a woman who flourished creatively but faltered socially. She became infamous for her racist, anti-Semitic views later in life — a reputation aggravated by being notoriously tight-lipped in the few interviews she gave. (Von Planta writes in the book’s introduction, “In the rare interviews she gave, her one-word answers were dreaded.”) And she refused to authorize a biography during her lifetime, leaving little material on her personal life in her own words.

Her career-long attraction to tales of murder and psychological games only deepened the enigma.

Upon beginning “Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks,” released by Liveright Publishing, one feels the suspense of reading a work many years in the making, containing such a heavy — and complicated — legacy. But, happily, it exceeds expectations. Highsmith’s tireless chronicle of her life, and its many emotional and mental highs and lows, is one of her most enduring works.

‘The International Daisy Chain’

The most surprising, and captivating, aspect of the book is the image of a young Highsmith that emerges in the early chapters: highly sociable, full of ambition and possessing a lust for life — and women.

The entries written during Highsmith’s college years and early post-graduate life, from the early- to mid-1940s, are a thrilling combination of whirlwind romances and fashionable scenes of World War II and post-war-era New York nightlife. During this period, she has dates every night, drinks heavily and renews her commitment to writing on a daily basis. She appears in love with love but crippled by her unwillingness to receive it — a quality that will ripen with age.

In 1950, a year marked by professional successes, a 29-year-old Highsmith writes an entry that begins: “The entire pattern of my life has been and is: She has rejected me.” These moments of self-doubt are punctuated by Highsmith’s frequent romantic exclamations, especially in the case of new love. In an entry from 1945, in the midst of a fresh romance and on the heels of the end of another, she writes: “God, how beautiful life is when it is illuminated by a woman!”

While she has brief affairs with men, they most often seem to be the product of societal and familial pressure rather than actual affection. Instead, the glamorous and heavy-drinking members of a society of older women remain the constant objects of her ever-roaming affections.

During those years, a boyishly alluring Highsmith enjoys her place as a favorite among New York’s cultural elite, chiefly in the company of famous lesbian and bisexual artists and socialites. As she enters the workforce, in 1942, Highsmith’s reliance on this social network only increases. She receives key introductions and recommendations that launch her as a young writer.

Joan Schenkar, who wrote the 2009 biography “The Talented Miss Highsmith: The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith,” charts the author’s professional rise through the patronage of these women in a fascinating afterword, titled “Pat Highsmith’s After-School Education: The International Daisy Chain.” Schenkar sheds light on the profound influence of these figures, to whom she credits Highsmith’s popular success, and how they would inspire the author’s writing for the rest of her life.

One of those women was Virginia Kent Catherwood. Catherwood, a Philadelphia heiress with whom Highsmith had a complicated series of affairs, would be one of the muses for her 1952 novel, “The Price of Salt,” later republished as “Carol.”

“Highsmith siphoned, as directly as a blood donation, the life history and styles of speech of Ginnie Catherwood (as well as the best version of her love affair with Ginnie) into a novel unlike any other she would ever write,” Schenkar writes.

Highsmith, who toys with the idea of writing a lesbian novel in the early entries, published “The Price of Salt” under a pseudonym at the encouragement of her agent. Although the novel was an immediate success, it still represented a reputational threat for the author, who lived a closeted life publicly despite being very much out in the open.

But the novel was clearly a labor of love for the author, despite her public disavowal. While in the midst of writing it, Highsmith writes an entry about its main characters that states, in part, “I live so completely with them now, I do not even think I can contemplate an amour (I am in love with Carol, too).”

The retitled “Carol” was published in 1990, with an afterword by Highsmith, and was later adapted into the 2015 film of the same name starring Academy Award-winner Cate Blanchett in the titular role. As Schenkar points out, it’s Highsmith’s most unique novel, deviating from the psychosexual relationships between homicidal men that populated her other widely popular works. Instead it’s a kind of love letter to “the high-powered, communally driven engine of the group of women and lovers Pat met in New York in the 1940s”:

“The steady hum of their exits from their marriages, their love affairs, their families, and their other social martyrdoms idles in the background of Pat’s least characteristic (and most true-to self) novel like the getaway car at a bank robbery,” Schenkar writes.

Follow NBC Out on Twitter, Facebook & Instagram

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com