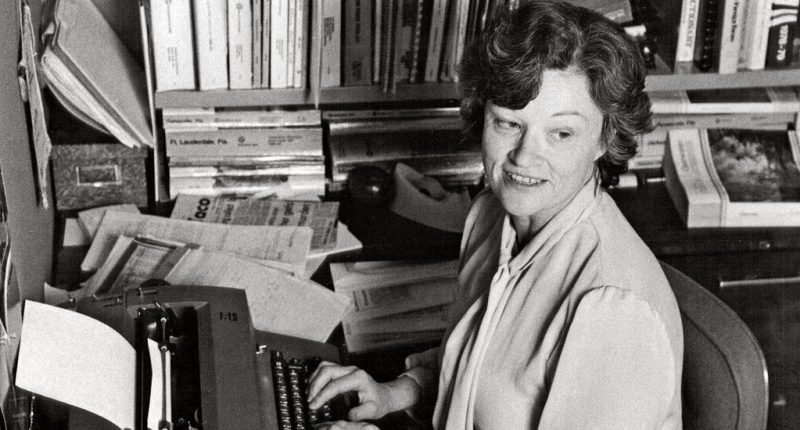

Lucy Morgan, a widely feared Florida journalist, died on Sept. 20 at a nursing home in Tallahassee, the state capital. She was 82.

The cause was complications of a fall, her daughter, Kathleen Bauerlin, said.

Feared. The word is not an exaggeration.

One former Florida sheriff reported seeing a group of local sheriffs walk around Ms. Morgan like a school of fish moving around a shark.

A Florida political strategist recalled that the first time he picked up a phone at campaign headquarters and heard Ms. Morgan on the other line, he stuttered in panic.

“If it wasn’t for you,” a state senator told Ms. Morgan in a profile of her published in 2005 by her longtime employer, The St. Petersburg Times, “we would probably steal the silverware.”

In the same piece, Ms. Morgan explained why she worked patiently on big stories. “You don’t want to shoot rubber bands,” she said. “When the time comes, you want a loaded gun.”

Her long career of journalistic gunslinging — taking aim at corrupt powerful men, firing off stories and taking home trophies, including a Pulitzer Prize — now seems to belong to a vanishing era of American newspapers.

Working at a daily not based in a major metropolis, Ms. Morgan nevertheless was given years to work on her projects and unstinting legal support when her work was challenged.

The event that made her a journalist, in 1965, was fittingly old-fashioned: a stranger with an idea knocking on the front door of her home in the little Florida town of Crystal River.

It was the editor of her local paper, The Ocala Star-Banner, which needed a new correspondent in the area. Did Ms. Morgan want the position?

“I’ve never written anything,” Ms. Morgan recalled saying in a 2014 interview with the publication Florida Trend. “Why would you come to me?”

The editor replied that Ms. Morgan’s local librarian had said that she read more books than anybody else in town. If she read so much, maybe she could also write.

Ms. Morgan began earning 20 cents per column inch of news writing. The next year she divorced her husband, Al Ware, a football coach, and took charge of raising their three children, bringing them along with her to late-night fires and car crashes.

She showed her mettle to a larger audience in 1973. Working on a series about public corruption for The St. Petersburg Times (now known as The Tampa Bay Times), she reported the private goings-on of a grand jury proceeding. The state attorney demanded that she reveal how she got the information. She refused.

She was sentenced to eight months in jail. The St. Petersburg Times called it “the heaviest contempt sentence on record against an American reporter.” Ms. Morgan posted bail. The case dragged on for three years, with imprisonment always a possibility.

In 1976, the Florida Supreme Court overturned previous rulings against Ms. Morgan and expanded press privileges in Florida, setting a precedent that local reporters still cite.

Her jail sentence, she told Florida Trend, “made me better known and trusted by the legal establishment and the ordinary citizen.”

Ms. Morgan’s credibility helped her launch investigations that upended several Florida sheriffs’ departments.

In 1982, she was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for local reporting for a series on drug smuggling in Dixie County.

“Before I was able to finish there, a whole bunch of deputies, a school board member, a county commission chairman and 250 other souls went to jail,” Ms. Morgan said in 2000 for an oral history published by the University of Florida.

Three years later, she and another St. Petersburg Times journalist, Jack Reed, shared the Pulitzer for investigative reporting for a series on the sheriff’s department of Pasco County. That series helped lead to the removal of the sheriff, John Short, and his indictment on corruption charges.

Ms. Morgan’s reporting showed, among other things, that one in eight officers in Pasco County had criminal arrest records, and that more than half had lied about their pasts to get certified. One officer had an outstanding grand theft arrest warrant for stealing a police dog in another Florida county. Another had been the wheel man in several armed robberies.

In 1994, Ms. Morgan’s reporting lent support to female inmates in Gulf County who said that the sheriff there forced them to give him oral sex in exchange for special favors. After the sheriff was found guilty of seven counts of violating the civil rights of female prisoners, Ms. Morgan returned to her office and found a dozen roses with a note: “From the women you believed.”

By that time, she had changed her professional focus.

“I went from looking at drug smugglers and public corruption and organized crime into state government and politics,” she said in the oral history. “Somehow, it seems like a natural transition. The drug smugglers were more candid than the state officials.”

When she was about 60, she shattered her right ankle in the Florida House press gallery. But she continued limping around the Capitol building, bringing a fog of Trésor Eau de Parfum with her wherever she went. She greeted the legislators, lobbyists and maintenance people she knew not by asking, “How are you?” but instead calling out, “You doin’ somethin’ bad?”

“No, ma’am” was a standard response. That did not satisfy Ms. Morgan. “Tell me something I’m not supposed to know,” she would insist.

Sometimes Ms. Morgan’s target would jovially retort that he was doing something bad. “You want to confess?” she would ask. Nobody could tell whether she was kidding.

Ron Book, a powerful Florida lobbyist, told NPR in 2012 that Ms. Morgan had been known to reach into his pocket and take his paperwork.

Her investigations exposed widespread misreporting of gifts to state politicians, indicating that many of them should be charged with criminal misdemeanors. They also exposed what Ms. Morgan herself nicknamed the “Taj Mahal” scandal, which involved slipping an appropriation of more than $30 million for a luxurious courthouse into unrelated transportation legislation at the last minute.

Ms. Morgan’s old colleagues regale one another with tales of her news gathering.

Charlotte Sutton, a former St. Petersburg Times reporter who is now managing editor of The Philadelphia Inquirer, recently recalled a dinner out with Ms. Morgan and her husband.

After drinks arrived, Ms. Sutton wrote on Facebook, Ms. Morgan began to eye another group at the restaurant. She excused herself and approached the men to chat.

By the time the main course arrived, Ms. Morgan had told The St. Petersburg Times to save her a top spot on the front page of the next day’s paper. While eating dinner, she dictated the news to the night editor: Lawton Chiles, a popular former U.S. senator from Florida, was coming out of retirement and running for governor.

“Lucy had it first,” Ms. Sutton wrote. “Long before dessert.”

Lucile Bedford Keen was born on Oct. 11, 1940, in Memphis and grew up in Hattiesburg, Miss. Her mother, Lucile (Sanders) Keen, ran a drugstore. Lucy recalled her father, Allin, as an alcoholic, and her parents’ marriage broke down within months of her birth.

When she was 17, Lucy got pregnant and married Mr. Ware. In 1968, about two years after they divorced, she married Richard Morgan, her editor at The St. Petersburg Times. In addition to Ms. Bauerlin, he survives her, along with another child from her first marriage, Andrew Ware; a stepdaughter, Lynn Ewell; four grandchildren; four step-grandchildren; two great-grandsons; and eight step-great-grandchildren. Another son from her first marriage, Al Ware, died in a car accident in 1979.

Ms. Morgan and her husband split their time between a home in Tallahassee and one in Cashiers, a town in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. While technically retired there, Ms. Morgan could not help uncovering a more than $50 million mortgage fraud scheme; as a result of her reporting, several people received substantial prison sentences.

As a woman in a man’s world, Ms. Morgan said, she saw advantages to being underestimated.

“When I open my mouth and speak Southern, it is disarming to the average man who has been in control of the world and not expecting women to play much of a role in that,” she said in the University of Florida oral history. “They assume I have no brain when they hear this Southern brogue, until it is too late.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nytimes.com