While the nation tracked Hurricane Ian’s movement throughout Florida, I was reminded of 14-year-old me, nearly 30 years ago, being thrust into adulthood in the aftermath of Hurricane Andrew. My hometown of Homestead, Florida, was rocked to ruins by the unforgiving winds of Andrew. With sustained gusts of 165 mph, the Category 5 storm snapped utility poles, flipped semis, leveled over 50,000 homes and stole 23 lives.

As adults, we’ve all had to bail out on plans for home maintenance. It’s a drag, but it’s part of life. Last week, I had to cancel a lunch appointment to meet with a plumber about an unruly garbage disposal. A month ago, I had to dip out of a doctor’s appointment to deal with a shotty roof job. In the fall of 1992, I called in absent from school because I had to be home to meet with the cabinet guy — one of my jobs in helping my family rebuild after Andrew.

In the fall of 1992, I called in absent from school because I had to be home to meet with the cabinet guy — one of my jobs in helping my family rebuild after Andrew.

Many parents picking up pieces after Ian will be left to fight several battles. Looters. Insurance companies. Contractors. But the biggest fight they might not see coming is the fight for their children’s childhood.

At just 14, I was a survivor and a part of a recovery process. In some cases because I was asked to be, but in most cases because I wanted to be. There was a house on the ground, a business to relaunch and a rebuilding that needed to begin. As I look back now, yeah, there was a lot of work to be done, but there was also a childhood to be lived.

When Hurricane Andrew made landfall, my family and I were huddled inside the lounge attached to our family-owned hotel. It was us and 110 rooms worth of hotel guests, their pets, the few belongings we had all packed, and our combined prayers.

I remember very few of their faces and none of their names. Much like Homestead itself, my memories of the storm are broken and scattered. A mental picture of a marquee sign twisting and turning before flying off, a snapshot of the roof of our town bowling alley being peeled away like the top of a tin can.

It was so dark that it was hard to get a good look at much. The sounds, on the other hand, you couldn’t escape.

There was the low moaning of the wind, banging, shingles being plucked off the roof, and the crying mixed with panic.

From what I was told, Andrew only lasted a few hours, but I was convinced it had been days.

Our home was gone, and so was the family business. Everyone’s everything was gone. People got lost trying to return to their homes after taking shelter.

When homes were found, they were unrecognizable — just glimpses and shards of what once stood. A tree was in my mom’s closet, our fridge was right where we left it, and the neighbor’s washing machine was in the front yard.

At the time, it never hit me to be sad about what was lost. I guess I was just grateful for what wasn’t. Plus, there was no time to mourn, only time to rebuild.

In the days that followed, I learned a lot about home construction and insurance claims. I joined my parents when they met with insurance adjusters, learned how to fire up a generator and chased down furniture trucks that were out and about selling goods.

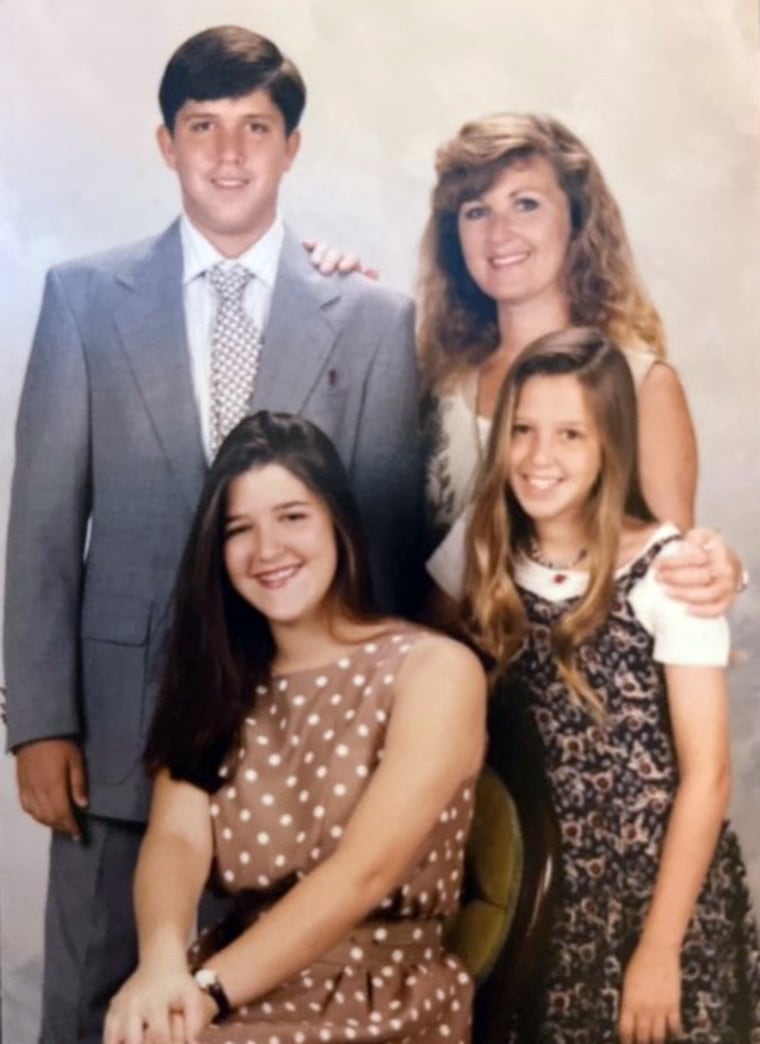

As children of Andrew, my siblings, friends and I were sometimes asked to pick up a hammer or to start tossing debris, and we did. No matter our ages (8-15 years old), we did what we could because it felt normal to be needed; it was a relief to be a help versus a burden. Helping also meant we were a step closer to moving our family out of a 30-foot camper. We’d end up living in it for eight months as we figured out the next steps.

There were very few days in that first year post-Andrew that I felt like a kid. The pressure to rebuild isn’t just felt by the parents, it is felt by the children too, and that’s what parents in the wake of Ian should know.

It’s something that I don’t think my parents were always aware of. Understandably, they were overwhelmed by trying to meet our basic life needs.

Indirectly and directly, I, along with my siblings and friends, felt a need to fix an adult-sized problem.

And the kids navigating the wreckage of Ian, not unlike us in the early ‘90s, will be changed by what they have seen and survived. They will long to get back what was lost.

Many will try to help, to be present, participate and talk shop. They will want to help their grandparents, neighbors, friends, churches and schools. They will bail out on classwork, homework and after-school practices to help with the house. They will be robbed of carefree days — talking by the lockers, practicing their jump shot on the basketball court and de-stressing with their friends. They will also lose out on the childhood luxury of treating everyday childhood hiccups like lifelong tragedies because, at the moment, nothing in their lives is trivial.

When the rebuilding process begins, it will be tempting for adults to accept help and hands wherever they can, even if they are child-sized.

When the rebuilding process begins, it will be tempting for adults to accept help and hands wherever they can, even if they are child-sized. So if it brings your child comfort to help, then let them.

Let them pitch in, claim a role in the fight, and learn about perseverance and grit. Have them experience the kindness and generosity that comes with tragedy. Sign them up for a crash course on drywall, tile and grout. Allow them to see the work that it takes to make something from nothing. Those life lessons kids learn will make them better and stronger. Let them know that they are wanted and welcome to a front-row seat of it all.

But in all that, parents and guardians need to be sure to remind kids — and remember themselves — that their attendance is not required at every moment. Hammer home that recovery is an adult-sized job and that being a kid is their No. 1 responsibility.

It won’t be easy to do, but parents gotta give it their best. Through the drills and the generators, it’s crucial to remind children that there is still silliness to be had, games to be played and shows to be binged. When it’s safe to be outside, and power is restored, it’s up to parents to remind themselves and their kids that they are still kids — not contractors.

There are bicycles to ride, friends to text and crappy love poems to write. Doing things like catching the football games on Sundays, driving an hour to the open movie theater or to the school dance in the makeshift auditorium is part of recovering, too.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com