“Sex sells” is one of the oldest aphorisms in advertising. But it wasn’t until the turn of the 20th century that the marketing world truly took notice of the male form. In large part, that was thanks to the work of commercial illustrator J.C. Leyendecker, whose ads were suffused with homoeroticism.

Leyendecker painted broad-chested Adonises that were used to sell everything from socks and underwear to razors and cigarettes. His most notable contribution, though, was the “Arrow Collar Man,” a dashing figure who promoted Cluett Peabody & Company’s removable shirt collars.

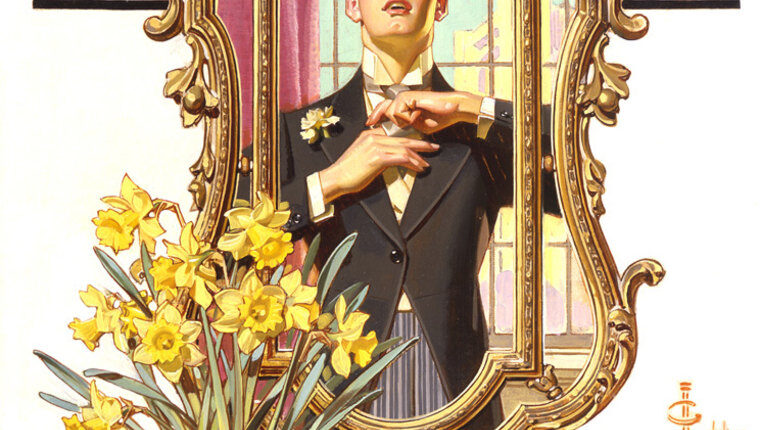

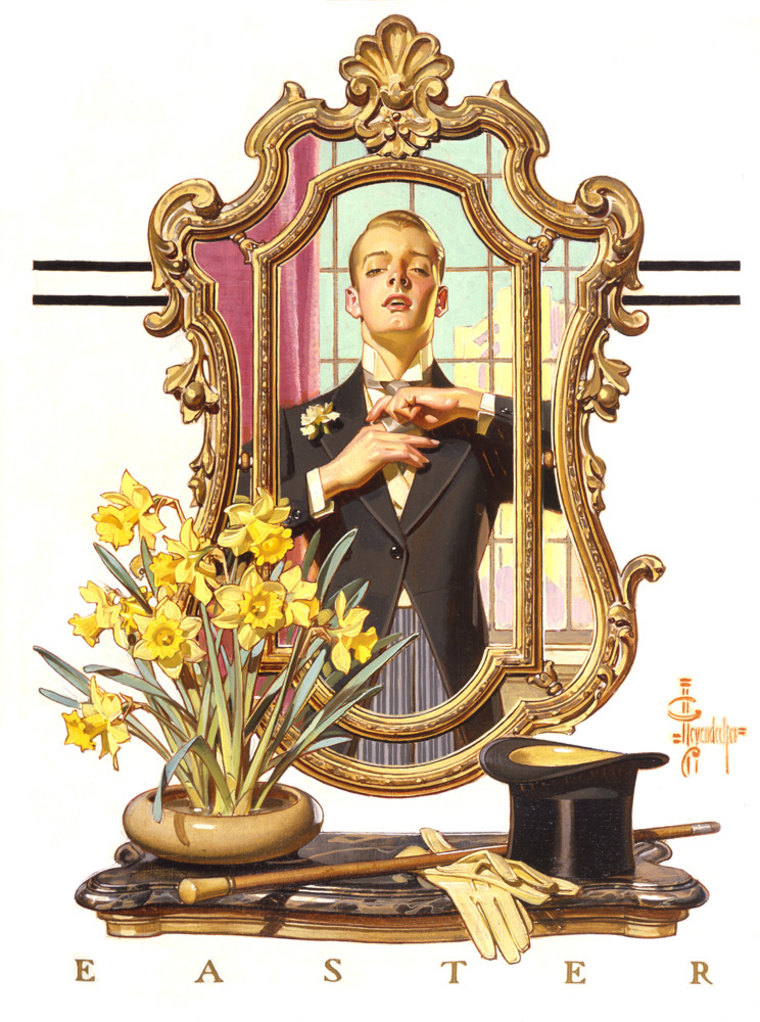

Leyendecker also painted 322 covers for the Saturday Evening Post, reportedly one more than his famous protégé, Norman Rockwell. From the 1900s to the 1930s, he was a household name: Both Leyendecker and the Arrow Collar Man were name-checked by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

But with the advent of the Great Depression and World War II, his urbane, effete mannequins fell out of favor.

Commissions dried up and Leyendecker painted his last Post cover in 1943, dying in relative obscurity in 1951.

Now, his work — and his legacy — are being revived in “Under Cover: J.C. Leyendecker and American Masculinity,” running at the New-York Historical Society through Aug. 13.

The exhibition features some of Leyendecker’s best known commercial work, as well as magazine covers, preparatory drawings and 19 original oil paintings, much of it on loan from the National Museum of American Illustration in Newport, Rhode Island.

“Up until Leyendecker’s era, men had their clothes made by a tailor,” advertising executive John Nash explained. “Now clothes were being mass-produced and advertised nationwide. Any man could look at Leyendecker’s work in a magazine or newspaper, or on a billboard, and want to be him. It opened up the idea of men as fashion consumers — and sex objects.”

Leyendecker’s Arrow Collar Man “was tall, muscular and white,” Nash said. “Practically Germanic. He was Ivy League-educated and athletic — the progenitor of today’s metrosexual.”

The model for the Arrow Collar Man, and many of Leyendecker’s figures, was Charles A. Beach, his business manager and, by most accounts, his longtime lover. The two shared a home in New Rochelle, New York, for nearly 40 years.

There are few primary sources to corroborate Leyendecker’s sexual orientation, but many modern historians — and the Historical Society exhibit — present him as a gay man.

“Leyendecker’s eye for capturing the male form was absolutely informed by his sexuality,” said Nash, who was the creative director who got Subaru to advertise to lesbians. “Was he going to that well purposefully or just instinctively? We just don’t know. But it’s definitely the visual world he wanted to create.”

“Under Cover” is broken into two main segments: One explores Leyendecker’s provocative depictions of the male body, including a Post cover featuring the god Apollo in a loincloth and an Ivory soap ad with a robed man who, according to the exhibit text, “appears to be sexually aroused.”

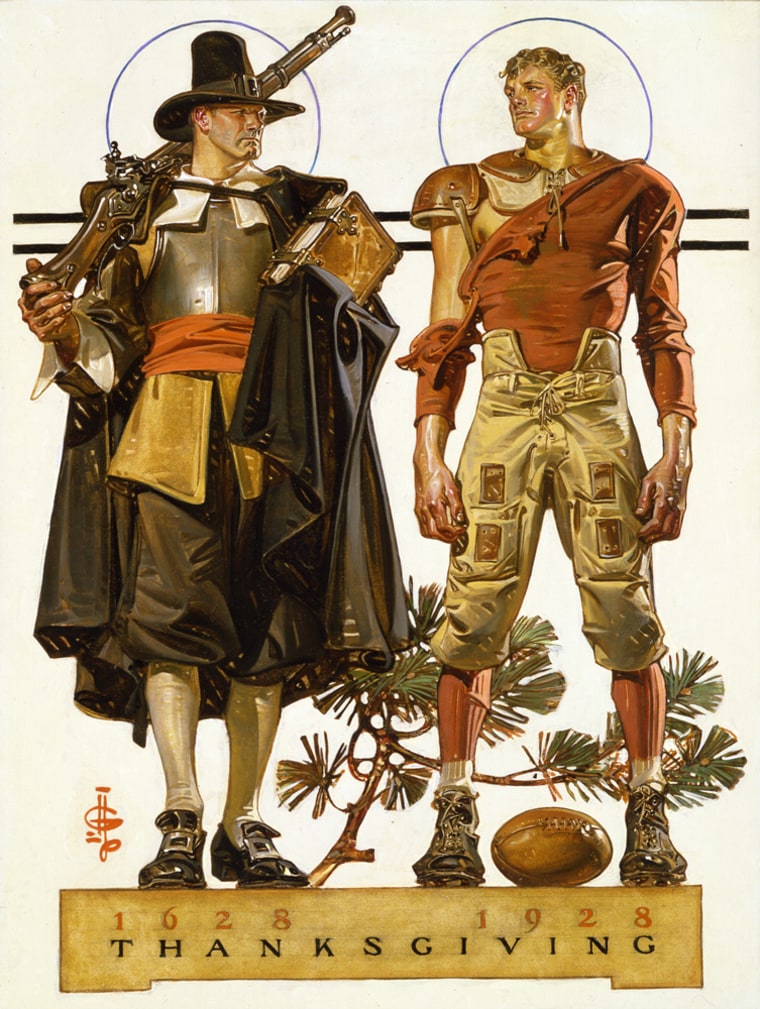

The other section explores his depictions of male intimacy, often through images of men sharing sexually charged looks.

In a Saturday Evening Post cover from Thanksgiving 1928, Leyendecker delivers a musket-wielding pilgrim locking eyes with a hunky football player whose right nipple is exposed through his torn jersey.

Some of his work did feature women, “but they’re almost completely ignored by the men next to them,” curator Donald Albrecht said.

In one well-known Arrow ad from 1910, a woman is sitting next to a golfer who is gently cradling his clubs and staring across the page at another man. Leyendecker’s work was frequently cropped based on the needs of the outlet and, in some iterations of this ad, the female companion is cut out entirely, leaving only the two men.

The executives at Arrow were probably focusing on how good the clothing looked, Nash said.

“The notion that there’s this cult of masculinity sailed right over their heads,” he said. “I don’t think they thought he was tapping into something primal about male identity.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com