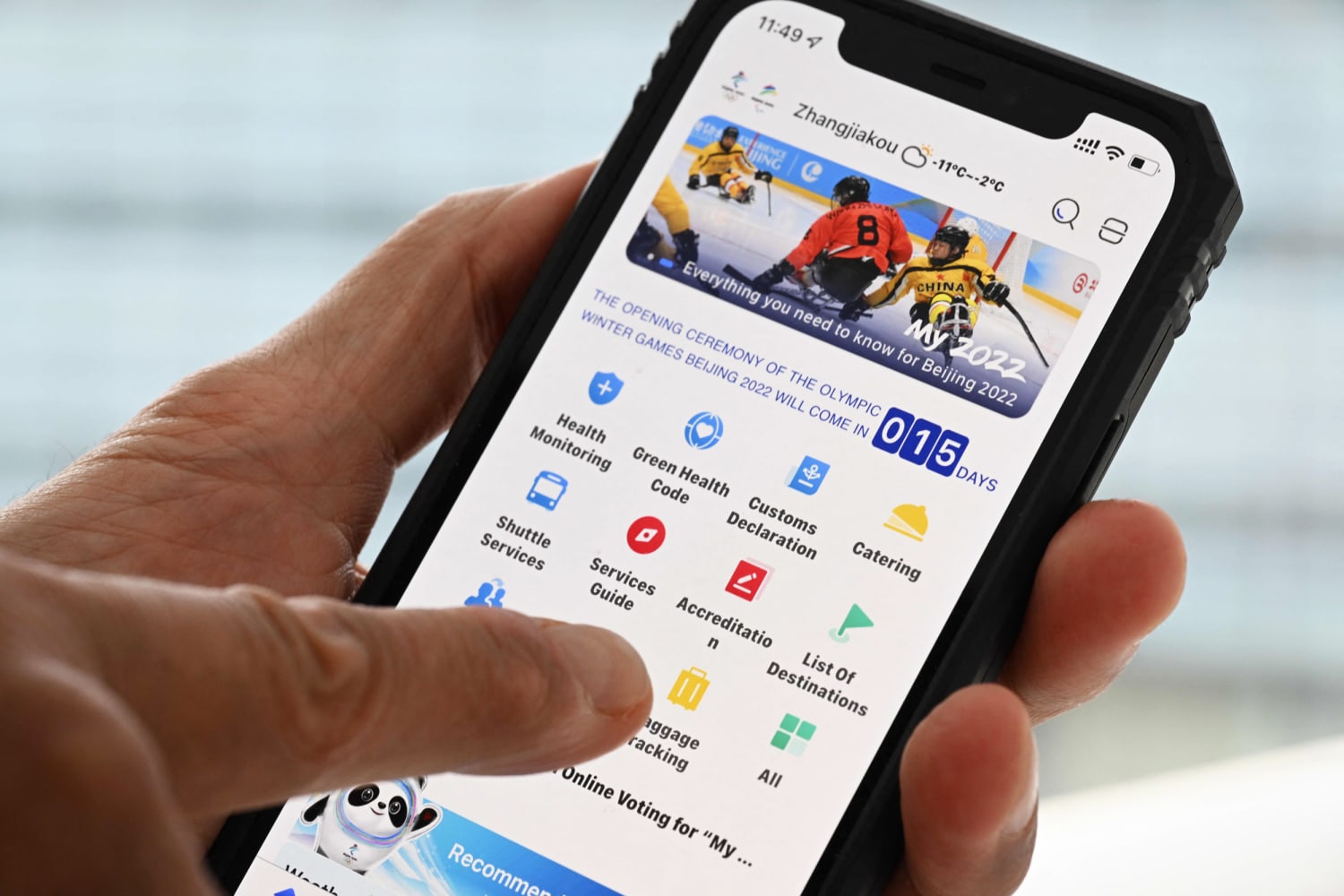

Sen. Ben Sasse, R-Neb., a frequent critic of China, took a firm stand on Friday against the smartphone app that everyone attending the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing is required to use: “Delete the spy app,” he urged in an op-ed article.

Sasse, noting that cybersecurity researchers had found vulnerabilities in the My2022 app, warned in the article that “CCP spies can use flaws in My2022’s security to steal data,” a reference to the Chinese Communist Party. He said that “authorities may have insisted on building these weaknesses into the app — but even if they didn’t, we can be sure they will try to exploit them.”

The article, published in the conservative publication National Review, came after researchers at Citizen Lab, the University of Toronto cybersecurity research center best known for identifying government-authorized spyware software on phones belonging to human rights activists and journalists, had raised the alarm in January about flaws in the My2022 app. Other concerns about My2022 have gone viral in recent days, especially one discredited claim, retweeted by the Spotify podcaster Joe Rogan, that it constantly records audio on users’ phones.

But focusing on that single smartphone app is a red herring, cybersecurity experts say, in the context of China’s larger appetite for the personal data of people around the world.

“If you are an Olympian in China worried about state surveillance, this app should be far down your list of worries,” said Priscilla Moriuchi, a nonresident fellow at Harvard University’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs and a former China specialist at the National Security Agency.

“As for Chinese state surveillance, it is omnipresent and they do not need audio from this app,” Moriuchi said.

Citizen Lab’s biggest problem with the app (that it sent sensitive user data without properly encrypting it) was fixed several weeks and two software patches ago, Citizen Lab director Ron Deibert said in an email. After Citizen Lab’s initial paper on the app was published, “the developers reached out to us, and we gave them instructions on how to fix the problems we identified,” he said.

And the claims that it constantly records audio are unfounded, Citizen Lab and other cybersecurity researchers said.

Will Strafach, the creator of an iPhone app that blocks location trackers, said he looked at the code of the My2022 app after seeing claims that it records its users’ surroundings. He found a single instance in which the app could trigger a phone’s microphone: when they were actively using its function to translate speech.

“Looking at the code, you look at anything that calls anything microphone related, and there’s nothing beyond this overt translation function,” Strafach said.

“There’s nothing surreptitious going on. It’s literally not in the code. I don’t know how else to say it,” he said.

In an emailed statement, a spokesperson for the International Olympic Committee defended requiring athletes to use the app to report health information like their temperature, citing the need to strictly monitor potential Covid-19 outbreaks.

“We are currently in the middle of a global pandemic and, like for the Olympic and Paralympic Games Tokyo 2020, special measures needed to be put in place to protect the participants of the Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games Beijing 2022 and the Chinese people,” the spokesperson said.

While worries about the app may be misplaced, they reflect legitimate concerns about the enormity of China’s appetite for people’s data, whether of its own citizens, foreigners abroad or travelers within its borders.

China is the most digitally surveilled country in the world, rife with cameras paired with facial recognition software. Its government legally gets direct access to practically all privately held data in the country. If China wanted to get visiting athletes’ sensitive medical data, for instance, it wouldn’t have to rely on a buggy smartphone app to get it.

While cybersecurity experts generally caution people traveling to China to bring only “burner” devices — a spare phone or computer, in case Chinese law enforcement decide to try to take the information that’s on it — this year, the FBI went so far as to announce ahead of the Games that it “urges all athletes to keep their personal cell phones at home and use a temporary phone while at the Games.”

For years, China also made a steady practice of hacking giant databases to collect Americans’ personal information, like their medical history, past government work, Social Security numbers and travel patterns.

That means that it’s unlikely that China’s Olympics app is part of a plot to get access to athlete data that its security services likely already have and could certainly acquire.

“Chinese state surveillance is already so tightly integrated into the telecommunications infrastructure in China that state authorities would not need collection from one app to retrieve audio from specific users,” Moriuchi said.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com