Most elections fit in one of two categories: a referendum on one person, party or idea or a choice among competing people, parties or ideas.

Whether an election ends up being more of a referendum or more of a choice between two equally compelling (or repellent) candidates usually depends on what type of campaign is run, with most campaigns organizing themselves around one of these two theories.

For the most part, candidates and parties out of power usually try to make campaigns referendums on the incumbent candidate or party. That was true in 2004, when John Kerry tried to make the presidential campaign all about George W. Bush’s leadership of the economy and the war. The Bush campaign was determined to fight the Kerry campaign’s construction and wanted to disqualify Kerry, making wavering swing voters think twice about simply using their votes to express displeasure with the incumbent.

A similar phenomenon took place in 2012, with the party roles reversed. Mitt Romney got the most traction whenever the campaign narrative became more of a referendum on Barack Obama’s handling of the economy specifically and Washington generally. But, like Bush’s, the Obama team was determined to make the election a choice between two competing visions. One line from that campaign stands out to me as quite illustrative of this successful shift by Obama: The incumbent played off the old Ronald Reagan question from 1980 — “are you better off now than you were four years ago?” — and asked voters “are you going to be better off four years from now” under Obama policies or Romney policies.

In 2016, we saw one of the great misinterpretations of a campaign in a long time. Both parties were convinced their best path to victory rested solely on turning the campaign into a character referendum on the other nominee. The campaigns of both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump messaged their campaigns accordingly. And swing voters waffled at times, it seemed, on whether they were voting for their candidate or voting against the opponent.

While many Washington elites and the professional media class believed the final votes would ultimately come down to a character-based referendum on Trump, it turned out these folks were half-right: It did come down to a “character-based referendum” — but on Clinton.

The cleanest examples of “anti-incumbent” campaigns were in 2008 and 2020, one a referendum on a party (the GOP in 2008) and the other a referendum on a person (Trump in 2020).

And that brings us to 2024 and the battle between the two likely major-party nominees to make this campaign a referendum on the other guy.

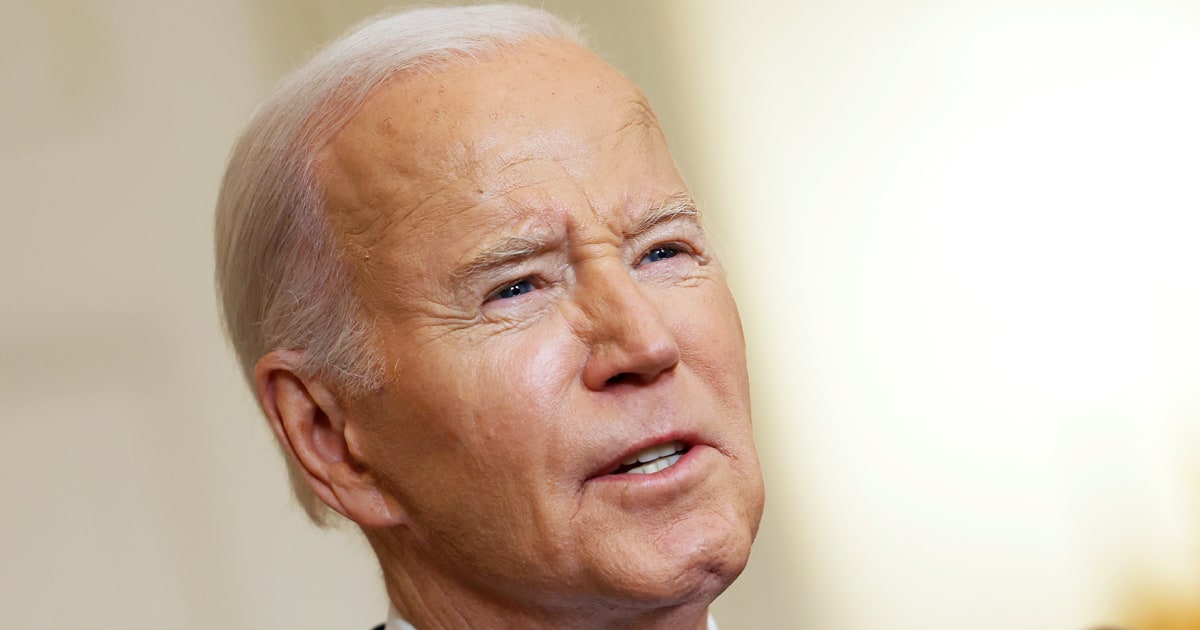

Right now, as our latest poll has indicated, many swing voters view this election as a referendum more on Biden than on Trump — for now. The simple fact that more voters believe age is a bigger concern for Biden than the legal issues are for Trump shows the potential for this campaign to turn more into a negative referendum on Biden.

Of course, Biden does have one giant advantage in terms of avoiding a referendum solely on him: Trump’s erratic behavior.

This weekend was the latest example of Trump’s caring more about airing and defending a grievance than he does actually winning an election. In Campaign 101, they teach you that when your opponent is in the midst of a negative feeding frenzy, simply get out of the way. But Trump, as he has demonstrated numerous times, appears to be incapable of self-control, so he went on an anti-NATO rant that would have found common cause with Russian’s own English-language propaganda arm, RT. Trump has made it clear: He really doesn’t care if Ukraine ends up a part of Russia. And that lack of conviction scares the living you-know-what out of our allies in Europe.

In fact, many semi-alarmed Washington Democrats comfort themselves about Biden’s current standing because Trump is the opponent. That’s why, despite the primal scream from voters demanding a different option (including half of Democrats), there are so few members of the Democratic establishment elite who feel comfortable going public in agreeing with that sentiment, for fear of being attacked for offering aid and comfort to Trump.

This brings me to the question of whether Biden wants a “choice” election or not.

Obviously, the campaign wants to avoid the election’s becoming a referendum on Biden and his ability to function in the job. And if Democrats want it to be a choice election, do they want it to be a choice based on character or on policy? I think the obvious answer is that, despite how tempting the character argument looks, it’s probably smarter (and safer) to attempt to make this a choice election based on policy.

That’s because if there’s one enduring lesson of the last 30 years, it’s that character rarely counts with voters. We preach that it does, but voters usually vote on character only when they feel they have the luxury — meaning their own lives are going well both culturally and financially. Character-focused campaigns failed against Bill Clinton twice, they failed against Trump in 2016, and they failed in the primaries against Trump this election cycle because even if the voters didn’t like the behavior of the men, they did like what they were saying or promising.

Now, I’m not saying ignore Trump’s bad character. But I’d basically use the character argument in only a few ways, including how his behavior impedes the opportunity to find consensus on thorny issues — which was the hallmark of Trump’s unsuccessful first term. He let so many opportunities for bipartisan wins go out the door simply because he couldn’t help himself. He is always his own worst enemy. It’s a defining characteristic of his failures in business and politics, many of which could have been avoided simply by his behaving less erratically.

But the character argument really works only for that small slice of college-educated voters who may philosophically lean right on fiscal and cultural issues but can’t stomach voting for him — basically, the folks at the likes of The Bulwark and the Lincoln Project!

If character is out, then clearly the Biden team has to ground its “choice” argument more in policy. So what does the second-term agenda look like, you ask? Good question, because so far, most of the rhetoric about a second term from either Biden or the White House generally is some form of “finish what we started” or “preserve and enact what we’ve already done.”

Perhaps Biden will use his State of the Union address in March — just two days after Super Tuesday and most likely the unofficial end of the primary season — as the place to lay out what he wants to get done in a second term. Whenever he does it, he needs to start doing it soon. I think the lack of an agenda his campaign can rally around only makes the other concerns of the Biden base more acute, including the president’s physical limitations.

I think part of the lack of enthusiasm of the Biden base is due to the missing agenda piece. Whatever one thinks of Trump, his vision for a second term is quite vivid. In fact, I’d argue the nonactivist media has spent a lot more time focusing on what a second Trump term could mean than it has on what a second Biden term would mean. And a big reason for that is that Biden hasn’t really offered up much about what more he wants to do.

That doesn’t mean Biden should campaign on unrealistic things, like canceling all student debt, but he needs to outline an agenda that’s both aspirational and realistic. And at some point, he needs to address the voters who aren’t happy with his tenure but still might vote for him because they can’t stand Trump.

How is he going to promise that Washington, under his watch during a second term, will become less dysfunctional than it was during his first term? Because I think he does need to promise that to the exhausted, depressed middle of the electorate. Obama used to use the construction “the fever will break” in the GOP if he got a second term. It turns out he wasn’t right, but it was something that seemed realistic enough to promise the moody moderates.

Perhaps Biden makes a similar promise, even though his assurance early in the 2020 campaign that a Biden win would cause a gridlock-breaking GOP “epiphany” proved false. Perhaps Biden argues that a second defeat of Trump would really break the fever in the GOP and push it to be more forward-looking, rather than simply be a party defined more by what it doesn’t like in America. But the point is Biden needs to start campaigning for something more than just “not Trump” if he has any hope of building enthusiasm among his own voters.

Of course, there could be another explanation for why the Biden team has been reluctant to talk up a second-term agenda: fear of dividing its own base.

This fear of dividing the Democratic Party is something Matthew Yglesias offers up in his influential Substack this week as an alternative theory for why the Biden White House is so protective of Biden’s public appearances.

“His staff have an incorrect theory of American politics,” Yglesias writes, arguing the Biden campaign apparatus and White House operatives all subscribe to a base mobilization strategy that calls for avoiding any issues that could disrupt or annoy the Democratic base. And he also believes Biden’s staff and the activists who make up the various identity and issue factions of the Democratic Party are, essentially, much more progressive and secular than Biden himself is.

So if you believe the best way to win an election is to simply mobilize your core supporters and you work for a president of another generation, you may fear putting him out there and contradicting a belief or a talking point that would make one of your base groups angry. Yglesias notes the example of Biden, in the early aftermath of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, getting attacked by certain factions on the left because he continued to express a personal position on abortion through the prism of his Catholic faith. That is, that he’s personally conflicted even if he’s not politically conflicted.

All of this goes back to the debate inside the Democratic Party about which direction it should take to win general elections. The progressive wing is definitely on the rise, and progressive adherents are now running most parts of the Democratic Party’s formal and informal structure. In fact, I’d argue that Biden is most likely personally to the right of most of his most vocal supporters.

Yglesias concludes: “We have a clear public record that it is Team Biden’s considered opinion that Joe Biden’s pre-2016 record in politics is cringe and bad and that they need to craft a different, more progressive persona for him. If you think that strategy is correct, then it follows that unscripted events are dangerous. Not because he might accidentally say Mexico when he clearly meant Egypt, but because he might accidentally say he has religious objections to abortion when he does, in fact, have religious objections to abortion.”

Many progressives don’t accept the premise that primary voters chose Biden in 2020 because they thought most of his primary opponents were too liberal to win. They believe he got the nomination simply because Covid short-circuited the primary debate and forced a quick consolidation.

But is it also possible that Biden was seen as the acceptable alternative by many Democrats and non-Trump Republicans simply because he was more moderate than the base of the Democratic Party? What Biden’s staff treats like a bug in dealing with the key interest groups that make up the Democratic coalition is most likely a feature for many middle-of-the-road voters. And unscripted Biden is more likely to sound like a moderate than scripted Biden. And let’s not forget, when voters themselves are asked to self-identify their ideologies, “moderate” and “conservative” are always first or second in some order. “Liberal” is always third.

Why NATO is in trouble in America

NATO has more than a Trump problem. NATO has a Republican Party problem.

The issue of NATO, of course, all depends on your own point of view. But I’d be careful being too dismissive of the growing isolationist viewpoint inside the GOP as something that’s just a product of Trump’s rhetoric. Many families in rural America, where isolationist sentiment has gotten the most traction, saw many of their sons and daughters sign up for service to fight in Iraq and Afghanistan — two wars that many Americans now aren’t convinced were worth it. Sure, we got bin Laden and helped Iraq start a fledgling democracy, but was the price in line with the result?

It’s that recent experience that has many hawkish Republican elected officials starting to rethink their stances on these issues if they want to get re-elected in this iteration of the GOP.

To put it another way, answer this question: Would it better position a Republican candidate to win a primary by being for more aid to Ukraine or less? I’d argue that in most areas of this country, it’s easier to navigate a GOP primary without Ukraine on the agenda.

So, yes, Patti Davis, we are a long way from your father Ronald Reagan’s GOP when it comes to “peace through strength.” In fact, we are much closer to the Republican Party of the Calvin Coolidge era than we are the Reagan era.

When out of smart ideas, blame the media

I’ve promised myself (and my editors) that I wouldn’t turn this column into a place to debate the role of the media in our politics. But the amount of lazy and sloppy analysis of the media that exists these days is truly astonishing. So for those in the content creation business who think media-bashing is the best way to grift people into giving them their clicks and attention, try a little accuracy.

- “The media” includes both MSNBC and Fox News, so I’m not sure how you can claim “the media” leans one way or the other. If you want to make a point about a specific media outlet, fine, but put away the broad brush.

- If you think media coverage is worthy of news coverage, then you haven’t been much of a journalist. Most media coverage is unworthy of attention from journalists whose job is supposed to be about surfacing information the public needs to live their lives.

- In terms of volume, both in amplification and pure social media mass, it’s clear the totality of it produces narratives that lean right, not left. I’d be eager to see some academic study proving me right or wrong on this, but when looking at key amplification metrics, the evidence is pretty compelling that taking media altogether shifts the conversation rightward.

Here’s my basic answer on media bias: All humans are born with “original bias,” so trying to disprove bias is, well, inhuman. Most well-funded newsrooms — and by “well-funded” I mean newsrooms that care as much about editors as they do reporters — care more about fairness and accuracy than they do balance. How does one “balance” the truth? That’s why “fair and balanced” is a right-wing dog whistle and not a mainstream journalistic ethos.

The largest group of media entities these days is not the well-funded newsrooms but the small specialty shops that promise to be biased in their coverage — biased either by an issue, toward a person or for a point of view. And it’s this group of “media” that gives the “fairness and accuracy” crowd its bad name. Many in this second group of media entities have premised their business model on creating the narrative that the larger news organizations are biased against them in some way. This creates the echo chamber effect about “media distrust,” with a whole slew of mom-and-pop “media” outlets/newsletters searching for any large media mistake to amplify as a way to build up their own fledgling followings.

Of course, when these smaller media entities make factual errors or are intentionally biased, they don’t get any scrutiny. In fact, I’d argue the pursuit and fact-checking of the bad-faith media actors has driven some journalists and well-meaning media outlets into a bad place on press freedom and freedom of thought in general.

Bottom line: Believe what you want about any specific media outlet, but just try to realize “the media” these days has never been this diverse ideologically and this “diverse” factually. So be careful conflating honest brokers with the dishonest grifters whose sole source of income is outrage clicks.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com