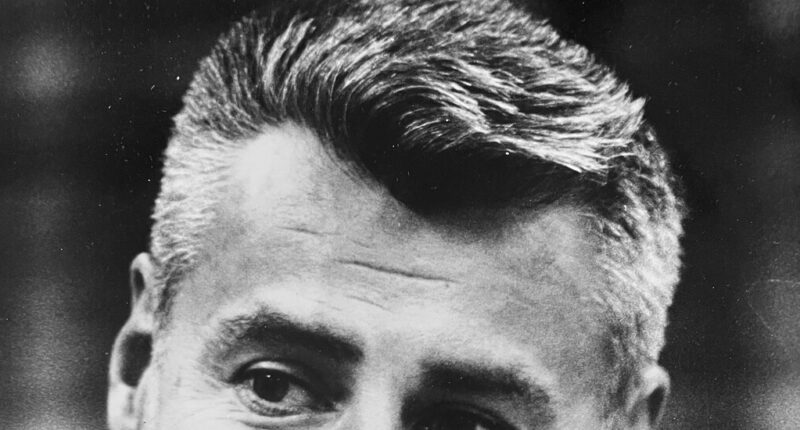

Carlo Vittorini, who as publisher guided Parade magazine, the nearly ubiquitous weekly Sunday newspaper supplement, to revenue and circulation heights, died on June 25 at his summer home in Nantucket, Mass. He was 94.

His wife, Nancy Vittorini, said the cause was congestive heart failure.

Mr. Vittorini spent 50 years in the magazine business, nearly all of it when it was still thriving. In 1992, when Parade’s circulation was soaring, he confidently told The St. Joseph News-Press/Gazette of Missouri: “Nobody can get a message out as quickly as we can. Even Time and Newsweek can’t reach the spectrum of people we can.”

In 1979, he was hired by S.I. Newhouse Jr., the chairman of Advance Publications, as Parade’s publisher, president and chief executive.

Parade’s advertising revenues were $140 million when Mr. Vittorini took over; he pushed that number to nearly $450 million in 1994, when a full-page advertisement cost $640,000 (the equivalent of about $1.3 million today), comparable to the price paid for TV commercials.

“We’re the equivalent of what Ed Sullivan used to be,” he told Bloomberg Business News in 1995, referring to the host of the Sunday-night television variety show that offered entertainment for the masses for 23 years before going off the air in 1971. “But our ratings are more stable and our show every week more predictable.”

By 1998, Parade was distributed in some 330 newspapers, giving it a circulation of 37.5 million. Its circulation had been 21.5 million when Mr. Vittorini was hired.

By then, Parade was offering a familiar product that slipped out of Sunday papers that were still fat: Walter Scott’s Personality Parade, a page of questions and answers about celebrities; the former New York magazine editor James Brady’s interviews with Hollywood stars; columns by Marilyn vos Savant, who was billed by the magazine as having the highest recorded I.Q.; and ads from the Franklin Mint, tobacco companies and “as seen on TV” products like the Thighmaster.

Parade had competition from another Sunday supplement, Family Weekly, which was renamed USA Weekend after its acquisition by the Gannett Company, the publisher of USA Today, in 1985. After that acquisition, 123 papers switched to Parade and 13 others, owned by Gannett, switched to USA Weekend.

In the San Diego market, the afternoon paper, The San Diego Tribune, decided to distribute USA Weekend, while the morning paper, The San Diego Union, continued to take Parade. Mr. Vittorini recalled meeting with Helen Copley, the papers’ owner, and telling her that he preferred that Parade be exclusive in all its markets. He warned her that he would stop distribution of it in The Union if she didn’t drop USA Weekend from The Tribune.

“Somewhat haughtily, she said to me, ‘Young man, how dare you tell me how to run my newspaper!’” he wrote in an unpublished memoir. “And politely as possible, I replied, ‘Mrs. Copley, I promise I won’t tell you how to run your newspaper if you don’t tell me how to run my magazine.’ Success: USA Weekend was dropped.”

Carlo Vittorini was born on Feb. 28, 1929, in Philadelphia and grew up in Haverford, Pa. His father, Domenico, an Italian immigrant, was a professor of Romance languages at the University of Pennsylvania; his mother, Helen (Whitney) Vittorini, a homemaker, had met her future husband when she took one of his classes.

Carlo graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1950 with a bachelor’s degree in English. He began his career in promotion work, then became a merchandising manager at The Saturday Evening Post in 1956 and a sales representative at Look magazine in 1958. For a dozen years, starting in 1965, he worked at Redbook magazine, where he rose to publisher and president.

In 1977, he was appointed the president of the Charter Company’s magazine group, which included Redbook, Ladies’ Home Journal and Sport magazine. A year later, he was hired to start a new magazine division at the Toronto-based Harlequin Enterprises, which is best known for publishing romance novels.

After barely a year at Harlequin, Mr. Vittorini was offered the job at Parade by Mr. Newhouse, whose company also published Vogue, Glamour, House & Garden and other magazines. Mr. Vittorini recalled that Mr. Newhouse handed him a three-ring binder of notes he had made about Parade over the three years since Advance Publications had acquired it.

“That evening, as I read his remarks,” Mr. Vittorini said in his memoir, “I realized that despite his acumen in the traditional magazine field, though he knew there was a problem, he was missing the solution for this nontraditional circulated magazine.”

He said that Parade’s unspectacular results improved quickly, partly because he got more newspapers to distribute the magazine, which helped raise ad rates.

He told Editor & Publisher in 1999: “We had some very basic goals, and it began with improving the product, intellectually and physically. There was a need to improve newspaper relations, and we did. The ad revenue came with it.”

In addition to his wife, who was Nancy Coleman when he married her, Mr. Vittorini is survived by his son, Stephen; his daughter, Lynn Vaughan; his stepdaughter, Ashley Frisbie; his stepson, Frank Coleman; and five grandchildren. His marriage to Alice Hellerman ended in divorce.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nytimes.com