Carl Fischer, the photographer who shot some of Esquire magazine’s most famous and provocative covers of the 1960s and early ’70s, including images of Muhammad Ali pierced by arrows and Andy Warhol falling into a giant can of tomato soup, died on Friday at his home in Manhattan. He was 98.

His granddaughter Alice Lloyd George confirmed his death.

Mr. Fischer, a self-taught photographer, had been working as an art director in advertising when, in 1963, Harold Hayes, Esquire’s editor, began engaging him regularly to shoot covers. He would ultimately shoot 60 covers for the magazine, usually working with the art director George Lois.

Mr. Lois, who died in November, was generally credited with the concept for a particular cover, but it was up to Mr. Fischer to figure out how to implement the idea and capture it on film. In the predigital age, that often meant seat-of-the-pants improvising.

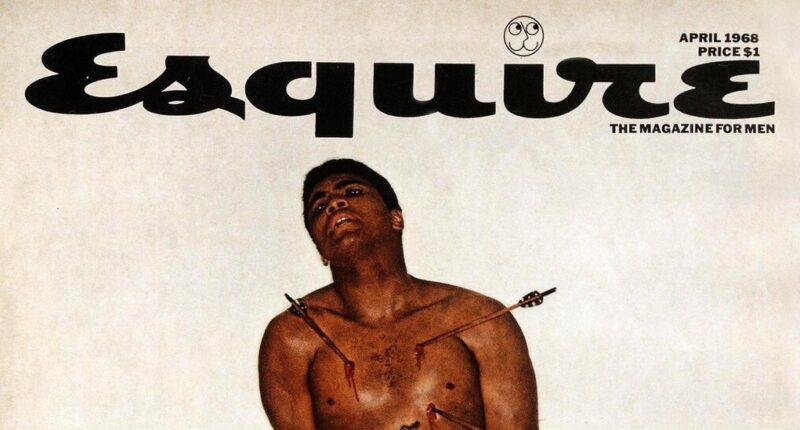

For example, for what was perhaps his most famous cover, from April 1968, the idea was to depict Ali in a way that evoked the Christian martyr Saint Sebastian. The year before, Ali had been stripped of his heavyweight title after he refused to be inducted into the armed forces on religious grounds.

Mr. Lois and Mr. Fischer intended to show Ali shirtless with arrows stuck in his body. It took some persuading to get Ali, a Muslim, to agree to the concept, since the Christian imagery bothered him. But once he did, there was an entirely different glitch.

“The arrows turned out to be a major headache,” Mr. Fischer told Esquire in 2015 for an article looking back on his career. “We’d practiced on a model beforehand, and when we tried sticking the arrows on the body with glue, they were so heavy that they hung down.”

So Mr. Fischer put a bar across the ceiling of his studio, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, and ran practically invisible fishing line from it down to the arrows to hold them up.

A number of his Esquire images were in fact multiple images, pieced together with what would today seem primitive photo collage tricks. The Warhol cover, for instance, showed Mr. Warhol seemingly drowning in a giant can of Campbell’s tomato soup. According to Mr. Lois, when Mr. Warhol was approached about the idea, he said, “But George, aren’t you going to have to build a giant can of soup?”

No; what was actually needed was a regular can of soup and some marbles.

“I dropped marbles in the soup,” Mr. Fischer said, “and tried to photograph the marble just as it hit the liquid so I could get a nice hole.”

Then Mr. Warhol posed with his arms flailing in the air as if he were drowning. The two photos were combined, and the resulting image was on the May 1969 Esquire cover.

Other times, it wasn’t the image that was manipulated but the subject. The was certainly true of the November 1970 cover, which Mr. Lois called “the most controversial of them all.” It showed William Calley, who had led one of the platoons responsible for killing much of the population of the South Vietnamese village of My Lai in 1968 during the Vietnam War, in a military uniform surrounded by children of Asian descent, with a grin on his face.

Mr. Fischer said that either Mr. Lois or Mr. Hayes — he couldn’t remember which — had called to tell him that Mr. Calley was coming to his studio and that he should find a half-dozen young children of Asian descent to participate in the shoot.

“Calley came to the studio not knowing the concept,” Mr. Fischer recalled in the 2015 interview, “and somebody, it was Lois or Harold, said, ‘Here’s what we’re going to do; this is going to show that you’re not a monster.’ I don’t know all the details of the conversation, but to this day I don’t understand why he ever did it, except that he probably thought it would make him look good.”

Mr. Fischer shot covers for other magazines as well, including dozens for New York, but the Esquire work attracted the most attention; some of those images are now in museum collections.

“Those covers were outrageous, they were insulting, they were infuriating and they were impressive,” Mr. Fischer told The Democrat and Chronicle of Rochester, N.Y., in 1978, when he was lecturing at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

“A lot of people were shocked,” he added. They would write in outraged over what they perceived as the messages of the covers, but Mr. Fischer said any messages were in the eye of the beholder.

“Actually, they didn’t really say anything in most cases,” he said. “It was all a matter of what you read into it, like all interesting art.”

Carl Fischer was born on May 3, 1924, in the Bronx to Joseph and Irma (Schwerin) Fischer. He grew up in Brooklyn and served in a communications unit in the Philippines during World War II.

In 1948 he earned a degree at the Cooper Union in Manhattan. He then won a Fulbright Scholarship to study at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design in London and bought a camera to take snapshots.

“One thing led to another,” he told The Democrat and Chronicle, “and I ended up spending about a year working in the darkroom, mostly alone, teaching myself how to take pictures.”

Back in New York, he worked as an art director in advertising, including for the Grey agency. His photography skills continued to develop, and they caught the eye of Mr. Hayes.

One of Mr. Fischer’s earliest Esquire covers, in December 1963, pictured the boxer Sonny Liston, who was Black, in a Santa Claus cap — a somewhat inflammatory image in the midst of the civil rights battles.

In the early 1970s Mr. Fischer had a falling out with Mr. Lois, largely over what Mr. Fischer saw as Mr. Lois’s tendency to take an excess of credit for the covers and not give much to the photographers he worked with. Certainly Mr. Lois drew most of the accolades for the Esquire covers, both at the time and for years afterward. In 2008, after The New York Times published a feature on Mr. Lois that did not mention Mr. Fischer, the photographer Helen Marcus, a former president of the American Society of Media Photographers, wrote a letter to the editor criticizing the omission.

“It is akin to publishing pictures of the Sistine Chapel and mentioning the pope who paid for them but not the painter,” she wrote.

Mr. Fischer continued to work in photography long after his Esquire heyday, and his work was the subject of gallery and museum shows. In 1949 he married Marilyn Wolf, who died in 2017. He is survived by his children, Kim, Douglas and Kenneth Fischer; four grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

In a self-published memoir, “Afterthoughts,” Mr. Fischer recalled how he made one particularly harrowing photo-collage cover for Esquire in 1970 centered on the actor Dustin Hoffman, who was making the movie “Little Big Man.” It superimposed an image of Mr. Hoffman amid Manhattan skyscrapers, looking gigantic, even taller than the buildings. To get the aerial image of the city, Mr. Fischer took a helicopter ride. He wanted a wide-angle shot.

“But to get that effect, it was necessary to both fly low and to get outside the helicopter as it banked,” he wrote. “I stood on the pontoon, tethered with a long canvas belt, made for the occasion, that allowed me to stand free of the fuselage so that the skyscrapers could be shot without part of the aircraft getting in the way. I marvel even now that, consumed by the problems and the noise, I was able to concentrate during that deranged procedure.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nytimes.com