SOMSERSET, Mass. — As deadly heat waves bear down across the globe, the Biden administration is warning that its office for dealing with climate change’s health impacts has no money.

President Joe Biden, in his first year in office, created an Office of Climate Change and Health Equity within the Health and Human Services Department, to prepare the nation’s health care system to deal with the growing and inevitable health effects of extreme heat, dangerous storms and worsening air pollution. The Biden administration asked Congress for $3 million to staff the office with eight employees, a paltry sum compared to the federal government’s multi-trillion-dollar budget.

But Congress has never funded the office, leaving the nascent unit with an uncertain future, lacking dedicated resources and reliant on a rotating cast of staffers borrowed from other government offices, even as the punishing summer temperatures makes clear the risks to human health: Nearly 2,000 already killed in this heat wave Spain and Portugal.

“Our hospitals are, for the most part, not completely ready,” Assistant Health Secretary Rachel Levine, a physician, said in an NBC News interview. “The health threats associated with climate change are very serious, and they’re growing.”

The office’s empty bank account is the latest example of how, even as Biden vows to use all his executive authority to act on climate if the Senate won’t, his hands are largely tied.

Last week, sweeping climate legislation fell apart in the Senate after Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va. — a key vote — said he wouldn’t support it unless data in the coming months shows inflation is improving. The collapse of that effort, already pared down several times, was the latest, potentially fatal blow to Biden’s climate and emissions-cutting agenda.

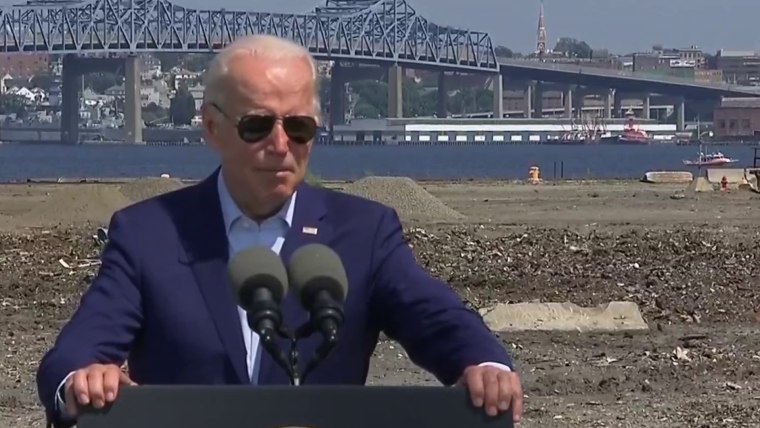

On Wednesday, Biden sought to show he’s taking action on his own wherever possible, visiting a former coal plant in Somerset, Massachusetts, which had been converted to a manufacturing facility for the offshore wind power industry. He announced $2.3 billion in funding through FEMA to help communities prepare for extreme heat and plans to allow the first U.S. offshore wind turbines in the Gulf of Mexico.

“This crisis impacts every aspect of everyday life,” Biden said, as temperatures in the waterside town surged into the 90s. He called climate change “an emergency” and added: “It is literally, not figuratively, a clear and present danger. The health of our citizens in our communities is literally at stake.”

House Democrats have supported the administration’s ask for $3 million for the climate health office, including the funding in a budget proposal for the 2023 fiscal year that passed a key committee, a House Appropriations Committee spokeswoman said.

Yet it’s unclear whether the funding will survive in the Senate. Congress may also opt to fund the government temporarily by passing a short-term extension of the previous budget, which would leave the climate office without funding once again.

With its limited resources and borrowed employees, the office has been working with federal agencies that provide medical services — such as the VA, the military and the Indian Health Service — to improve resiliency to climate change, Levine said. The office is also pushing hospitals and pharma companies to decarbonize, asking them to commit to a 50 percent emissions cut by the end of the decade, in line with Biden’s economy-wide goals.

Dr. Aaron Bernstein, a pediatrician who runs the climate health program at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, compared the lack of a coordinated approach on climate to the failures that led the federal government to create the Homeland Security Department after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

“We realized in an enormously painful way how our fragmented approach to protecting our national security made it possible for people to fly planes into the Twin Towers and the Pentagon,” Bernstein said, calling for the same level of urgency in responding to climate change. “We have no such response from our federal government right now.”

The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that around 1,300 people die every year in the U.S. from heat-related deaths, with hundreds more dying from the cold, severe storms and other climate-related events. A concerted government response, Bernstein said, could include steps like working with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to provide incentives for local health systems and front-line clinics to proactively reach out to patients ahead of extreme heat events, to ensure they have a plan to stay safe. The office could also work with the National Weather Service, which is housed in the Commerce Department, to issue heat-based warnings, similar to tornado warnings, Bernstein said.

In recent weeks, Levine has traveled the country meeting with mayors and local officials about their efforts to make their communities more resilient to extreme heat and climate change, and to minimize the negative health effects.

In Orlando, she was told of migrant farm workers unable to escape the heat outdoors, and in Seattle, of low-income families who can’t afford air conditioning. In the South Bronx, N.Y., and Albuquerque, New Mexico, she heard about urban heat islands that have higher-than-average temperatures due to lack of trees and shade.

In San Jose, California, Mayor Sam Liccardo said his city is getting “drier and hotter,” fueling new medical problems as wildfires aggravate respiratory problems. Wildfires and extreme heat have also triggered rolling power outages in California in recent years that have put the medically vulnerable at risk, he said.

“We’ve got a lot of medically vulnerable residents who depend on electricity for their respirators and dialysis, other kinds of devices critical simply to keep them alive,” Liccardo said.

Levine said the same communities disproportionately affected by pollution and health access disparities are also most at risk to climate change’s health effects: People of color, American Indians, seniors and migrants.

“Local officials are stepping up and trying to address this, but we need a national approach,” she said. “They all have the same messages: the challenge and threats to health from extreme heat.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com