Kept in the dark by federal agencies, his family turned to the nation’s courts this fall in a last attempt to seek accountability. Their civil lawsuit, filed against the federal government, the DEA agents, the city of Springfield and the local police officers who responded to the scene, alleges, among other claims, that Slay “posed no credible threat” to the federal agents — neither threatening them nor attempting to flee — and that their use of force was “grossly excessive.”

Over the past decade, some families of people killed by local police, like Michael Brown, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, have secured millions of dollars in high-profile civil actions against officers accused of excessive force.

But it remains difficult to win civil rights suits against law enforcement agencies, and payouts are rare. It will be even more difficult for Slay’s family because he was killed by a federal officer, which brings steeper hurdles in court than for families who sue local police.

A combination of federal laws and court precedent has rendered it difficult, if not nearly impossible, to successfully sue federal officers or local police officers who serve on a federal task force and receive federal legal protections — for excessive force and other civil rights violations. In the last six years, the Supreme Court has further narrowed that path, creating what one federal judge called a “Constitution-free zone” for federal law enforcement.

“You can’t prosecute them,” said Anya Bidwell, an attorney with the Institute for Justice, a nonprofit law firm that has argued similar cases in front of the Supreme Court. “You can’t sue them in state courts. And now you can’t sue them in federal court. There really isn’t any recourse.”

The Untouchables: read more of the NBC News federal law enforcement accountability series

- How the Supreme Court has effectively dismantled Bivens claims, the ability to file lawsuits against federal officials accused of violating constitutional rights.

- How federal law enforcement agencies under the Justice Department shroud their shootings in secrecy.

- How local prosecutors face steep legal barriers in charging and convicting federal officers of murder.

‘It happened very, very quickly’

On the afternoon of Nov. 2, 2020, DEA Agent John Stuart was in his unmarked van in the parking lot of a Springfield Walmart, watching what he suspected was a hand-to-hand drug deal at a nearby apartment complex.

Stuart and his partner, Anthony Gasperoni, had been trying to help a local task force officer find a suspect’s car. But the officer told Stuart the surveillance was off — he had lost track of the suspect.

Stuart then saw what looked like a second drug deal, he later told the Springfield Police detectives who investigated Slay’s death, and alerted Gasperoni. Both DEA vehicles began following a man from the second suspected deal, who was driving a U-Haul pickup. They tailed the truck into a neighborhood of single family homes, where it parked in front of Caleb Slay’s house.

According to the people who saw him last, Slay had spent that day at home. He helped a neighbor find his dog, worked on the sound system in his car and visited with his grandfather. A couple hours after his grandfather left, a friend came over.

Slay was sitting with the friend in a car in front of his house when the U-Haul truck pulled up. The friend would later tell the family’s attorney that both he and Slay were friends with the U-Haul truck’s driver, a man named Casey Ray. But Slay, the friend said, was waiting in the car for a ride from someone else.

Stuart, the DEA agent driving an unmarked van, pulled up behind the truck after it parked. Wearing a vest marked “POLICE,” he approached the driver’s side window of the truck. He identified himself to Ray as “police” — not as a DEA agent — and began asking questions.

Slay and his friend wanted to get away from the situation, the friend later recalled. Both of them got out of the car. “We didn’t even think he was a real cop,” he said, according to a transcript of his interview with the family’s attorney. “He’s in civilian clothing and he’s got a vest that anyone could get at any tactical store and buy and put a patch on.”

Stuart told investigators he thought he had interrupted a drug deal and asked both men to stay in the car, according to a transcript of his interview after the shooting.

“Nobody’s under control yet,” Stuart said. “I still haven’t got the driver of the U-Haul truck patted down or detained, and now I got this guy steppin’ out.”

Slay began walking toward his front door. Then Gasperoni, the other DEA agent, pulled up and got out of his car.

Four witnesses — Slay’s friend, Ray and two neighbors watching from across the street — saw what happened next.

Gasperoni, who like Stuart was in plainclothes and put on a police vest when he arrived, told investigators that he asked Slay where he was going and Slay responded, “in a very aggressive tone,” that he was going into his house. But, Gasperoni said, he asked Slay to come back and Slay did. “He complied at that time and just came right back over,” the agent said.

Gasperoni said that Slay then moved a hand behind his back and that he asked Slay not to reach behind him. Slay then put his hands out in front of him and told the agent that he was armed, according to both Gasperoni and Slay’s friend. Missouri law allows most residents to purchase and carry a concealed firearm without a license or permit, and Slay often carried a handgun in a holster on his belt.

One neighbor told police that Caleb seemed “very calm” as he held out his hands and the officer took hold of them. “Even his arms weren’t tense,” she said. “He was very, like, relaxed just standing there.”

The other neighbor also said that Caleb was calmly holding out his hands as he talked to the officer, according to the investigative report. “It kind of seemed like Caleb was like, ‘I’m not trying to do anything here,’” he said.

Slay’s friend recalled the same. “He’s just trying to tell him that he has nothing to do with this situation that’s happening in front of him,” the friend said. “The entire time Caleb’s hands stayed out in front of him. The entire time.”

Gasperoni saw Slay’s behavior differently. He said he grabbed Slay’s wrists and felt him tense up. Gasperoni shouted to his partner for help. Stuart then walked up behind Slay and grabbed his arm, telling investigators that as he approached, he indicated to Slay that he was going to detain him — though he couldn’t recall exactly what he said.

“I don’t know if I used the word detain or put cuffs on, but, you know, I’m tellin’ him, ‘Hey, this is….this is gonna happen,’” Stuart said, according to his interview transcript. “Because obviously everything’s going on and we can’t just….we can’t just let this guy have a gun.”

But three witnesses said that Slay reacted as if he was taken by surprise, with one neighbor telling investigators that the agent approached him from “out of nowhere.” Slay, who was larger than both agents, knocked Stuart over, his friend recalled, and the two men began to scuffle, with Stuart falling to the ground and Slay bent over him. Witnesses said Slay seemed to be pushing himself “off” the agent, shouting “get off me” — while Gasperoni said he saw Slay reach several times for his waistband.

Neither agent could remember what commands they gave Slay.

At one point, Gasperoni said he pointed his gun at close range at Slay’s head. Witnesses recalled him pressing his gun to Slay’s head and neck and shouting that he’d shoot Slay if he didn’t stop moving.

According to police records, Gasperoni fired three times, shooting Slay twice in the head.

“It happened very, very quickly,” he told investigators.

Police records show that neither the agents nor local police, who arrived later, rendered medical aid. Paramedics noted on arrival that Slay had a faint pulse, but he was not taken to the nearest ER, just two blocks away.

A spokesperson for the Springfield Police said they could not comment on pending litigation and also referred questions to the DEA. The DEA did not respond to questions. Attempts to reach the individual agents were not successful.

Slay was pronounced dead over the telephone by a doctor at 3:45 p.m., about 15 minutes after he was shot. Minutes later, his mother, Tina Slay Richardson, got a call from a family member who had just driven past his street and saw police lights.

She rushed over with Slay’s grandparents and his sister. They stood down the block, behind police, until dusk fell and a Springfield Police officer finally told them Slay was dead.

Slay’s friend and Ray were allowed to leave and the Springfield Police continued to process the scene. Local police later searched the U-Haul truck and found 9.11 grams of methamphetamine. NBC News was unable to confirm if Ray, the driver, was charged with a drug offense associated with the incident, despite a review of court records and inquiries to the prosecutor’s office.

“Caleb laid in that front yard until almost 11 o’clock at night,” his mother said. “Uncovered, handcuffed, face down.”

‘Little fear of liability’

The next morning, Slay Richardson hired an attorney, who began to help the family gather information about what happened that day. At the time, she had no idea how limited her legal options were.

Suing federal officials for misconduct has long been more difficult than suing local ones. After slavery, the federal government created a series of laws to protect Black citizens from being lynched by local police. One law enabled citizens to sue state and local government officials in federal court. But it didn’t let citizens sue federal officials.

It was a 1971 Supreme Court decision — Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics – that first opened the door for people to sue federal officers for violating Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable search and seizure. What became known as Bivens claims were later expanded by the court to cover allegations of cruel and unusual punishment and discrimination.

But almost as soon as the Supreme Court opened the door, federal judges began to shut it. Congress further limited such suits by outright barring Americans from suing federal employees in state courts.

In the last six years, the Supreme Court has revisited the issue three times, each time further narrowing the circumstances in which people can sue federal officials, to the point where legal experts say that Bivens is essentially dead.

Few successful Bivens claims over shootings have been brought against federal officers working for the DEA or other Justice Department agencies, experts said. An NBC News review of court records going back to 1971 and Treasury Department data found only five payouts for shooting claims against agents or officers with the DEA, FBI, U.S. Marshals Service or Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

“I think next time the Supreme Court gets a chance, they are going to get rid of Bivens,” said Jonathan M. Smith, a former section chief in the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division.

Lower courts have been following the Supreme Court’s lead. Smith, who oversaw investigations of police departments at DOJ and is now a civil rights attorney, represented a group of protestors who filed a Bivens claim against officers with the U.S. Park Police, Secret Service and local police who sprayed them with rubber bullets and threw flash-bang grenades during protests in front of the White House in 2020.

In 2021 a judge ruled the claims against local officers could go forward, but tossed all but one against federal officials, arguing that protestors should have filed under the Federal Torts Claim Act, a law that provides a narrow definition as to why a person can sue a federal official.

Torts claims can move forward legally for certain civil rights violations, but victims often can’t file class action suits, get a jury trial or demand court-ordered policy changes, and attorney fees are capped, making it harder to find a lawyer to take the case. Smith contends that without Bivens, the narrow torts claim act is a victim’s only legal recourse after an incident with federal officers.

In 2021, Judge Don Willett of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, stated it plainly in dismissing a civil rights suit filed against a Department of Homeland Security agent. “If you wear a federal badge, you can inflict excessive force on someone with little fear of liability,” he wrote.

No answers

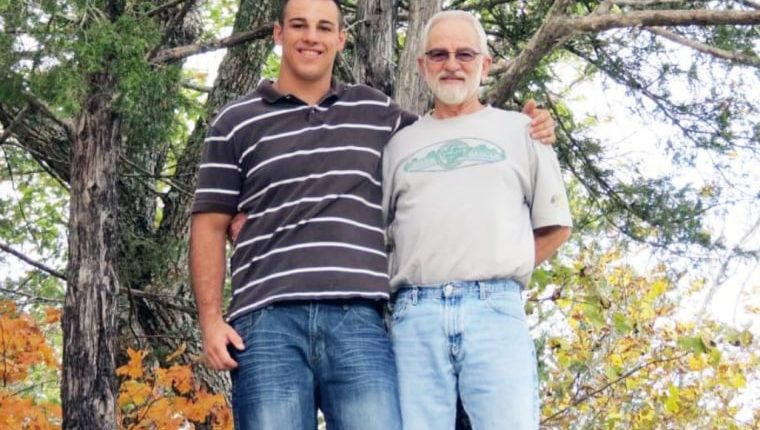

Before the pandemic, Caleb Slay, a former high school football star, worked as a bouncer at a nightclub. He was “kind of like the big brother to everybody,” according to his grandmother Dottie Slay.

But the isolation of the pandemic hit him hard. He lived alone, with only his dog, Prince, as a companion. His mother said he suffered from severe anxiety and attention-deficit disorder. The family knew he smoked pot, but were unaware of any other drug use — and were most concerned about what seemed to be a growing struggle with his mental health. Before his death, his family had called the police to perform well-checks, records show.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com