Anthony Back, a physician at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, knows many of his colleagues are hurting.

Over the past 21 months, they’ve weathered waves of infection, vaccine vitriol and hospital furloughs. At times, they’ve been isolated — in gowns, respirators and masks — from suffering patients whom they’ve been powerless to help survive Covid-19.

“The level of uncertainty and personal vulnerability and feeling like maybe you weren’t doing the right thing has really just been off the charts,” Back said. “These are physicians and nurses who experienced so much death firsthand.”

As health care professionals across the U.S. look for ways to deal with the mental and emotional anguish that has been wrought by the pandemic, Back is looking in a new, once-taboo, direction.

In a first-of-its kind clinical trial at the University of Washington, Back’s research team will treat 30 depressed medical professionals with a dose of synthetic psilocybin — a psychedelic drug — to see if the drug, along with psychotherapy, can reduce their mental anguish.

It follows small clinical trials of psilocybin in people with cancer and major depressive disorder that suggested it could help reduce depression and anxiety in these groups. Other research suggested the drug could treat alcohol use disorder.

That medical researchers are turning toward psilocybin to treat colleagues is representative of a growing curiosity and acceptance of the drug among those in the medical establishment.

“If this was done 5 to 10 years ago, I don’t think you would get approval,” said Dr. Stephen Ross, the associate director of the New York University Langone Health Center for Psychedelic Medicine.

The research also highlights concerns over burnout and depression among the workers the nation has leaned on for nearly two years.

“This is a serious crisis within medicine,” said Dr. Charles Grob, a professor of psychiatry at the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine. “We don’t have a good handle on how to provide in-depth, existential support for the front-line health workers.”

Back has experienced the anguish of treating Covid-19 patients. Back practices palliative care, which means he tries to help patients improve their quality of life and reduce suffering as they face serious illness.

Wearing protective gear, keeping distance from patients’ families and reducing bedside visits changed the nature of his work and that of colleagues. Then, as disruptions to surgery schedules and other impacts rattled the medical industry, hospitals furloughed or laid off workers. Later, interactions with patients in disbelief of Covid-19 became tense.

“People scream at you. They’re telling you you’re lying and that Covid is a hoax, and they’re spitting at you,” Back said. The result, according to Back, is a medical workforce with what he describes as a moral injury.

“There’s been a deep disillusionment,” Back said.

A survey of nearly 21,000 health workers last year found that about 38 percent said they had experienced anxiety or depression and 49 percent felt burned out.

More than half of health workers said their mental health had gotten worse during the pandemic, according to a report this fall from Morning Consult. About 18 percent of health workers quit a job during the pandemic and 12 percent had been laid off, the report said.

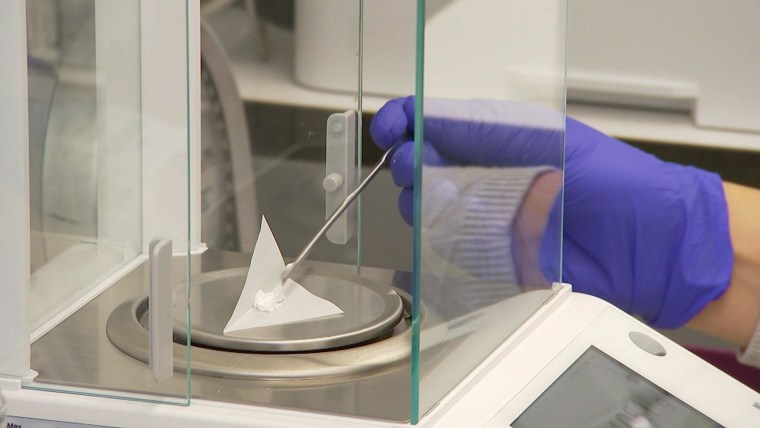

For the clinical trial, Back plans to enroll 30 health care workers who report moderate to severe depression related to the pandemic.

Each of the people involved in the trial will receive two psychotherapy sessions before they receive either psilocybin or a placebo drug during a six-hour session with two therapists. Three more psychotherapy sessions will follow.

Data and insights from interviews and questionnaires will help researchers understand the drug’s effect on the medical workers’ mind frame.

Back said the drug can release people from habitual ways of thinking and help them make fresh insights.

Back has taken psilocybin himself and wrote about his experience for the Journal of Palliative Medicine. The experience broadened his perspective on end-of-life care, he said.

Before, Back tried to help patients reinforce identities and practice letting go of things. He now places more emphasis on helping patients feel interconnectedness with others and belonging.

The use of psilocybin is not without some risk, Grob said.

Users can experience a worsening of mood, heightened anxiety or, in extreme cases, psychotic symptoms. Some people with risk factors shouldn’t take the drug, he said. Those receiving the drug ought to be screened. Facilitators need training.

“It’s serious medicine,” said Grob, who has no role in Back’s research and added that he views the work as responsible and timely.

At NYU, Ross and colleagues have administered more than 200 doses of psilocybin without a serious adverse event such as a hospitalization or death, he said.

Results from these studies and others suggest the drug could have a dramatic effect.

“The unique thing we’re finding with psilocybin is that it works rapidly to diminish depression and anxiety, and it has a long-duration therapeutic effect,” said Ross, who gave Back input on his clinical trial’s design but is not part of Back’s research.

In an August JAMA article, two prominent psychiatrists — William Smith of the University of Pennsylvania and Paul Appelbaum of Columbia University — urged caution about moving hastily with psychedelics.

Most of the promising studies are small and exclude people with histories of psychotic disorders or drug use, and it remains difficult to know how well the results those studied might translate to broader groups, they wrote.

Psilocybin remains a Schedule 1 drug, meaning the federal government considers it to have no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. Possession, even among researchers, remains tightly regulated.

Back had to get a green light from the Food and Drug Administration, a license from the federal Drug Enforcement Administration, a license from the state health department and approval from his university’s institutional review board to start this research. The process took nine months, he said.

Recent promising results have psychedelic drug treatments riding a wave of new public support and a relative gusher of funding for new science than in decades past.

From the early 1970s through the 1990s, “these were pariah treatment models, taboo. No one touched them,” Grob said.

Now, he added: “We’re entering into a new era where we’re taking a fresh look at psychedelics, where we’re not encumbered with the negative connotations that arose about psychedelics in the ‘60s because of its close connection with a politically active counterculture.”

Private funding opportunities have increased, and the regulatory agencies that decide what work to allow with these drugs have become more amenable to research, Grob said. Three foundations contributed to Back’s study, which will cost around $800,000, he said.

Even public funding is beginning to flow: A Johns Hopkins University researcher this fall received the first National Institutes of Health grant in more than half a century to study the therapeutic effects of psilocybin.

Back said he’s keeping an open mind to both perils and possibilities.

“Not every promising treatment pans out, and doing more to people isn’t always the best thing,” Back said.

The use of a substance that was once effectively verboten to treat doctors and other medical workers is a signal of both psilocybin’s promise and the severity of the pandemic’s impact on caregivers’ mental health.

“It’s a desperate situation, and sometimes desperate situations call for out-of-the box solutions,” Grob said.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com