Right about now, Sarah Palin is likely thinking the fix is in.

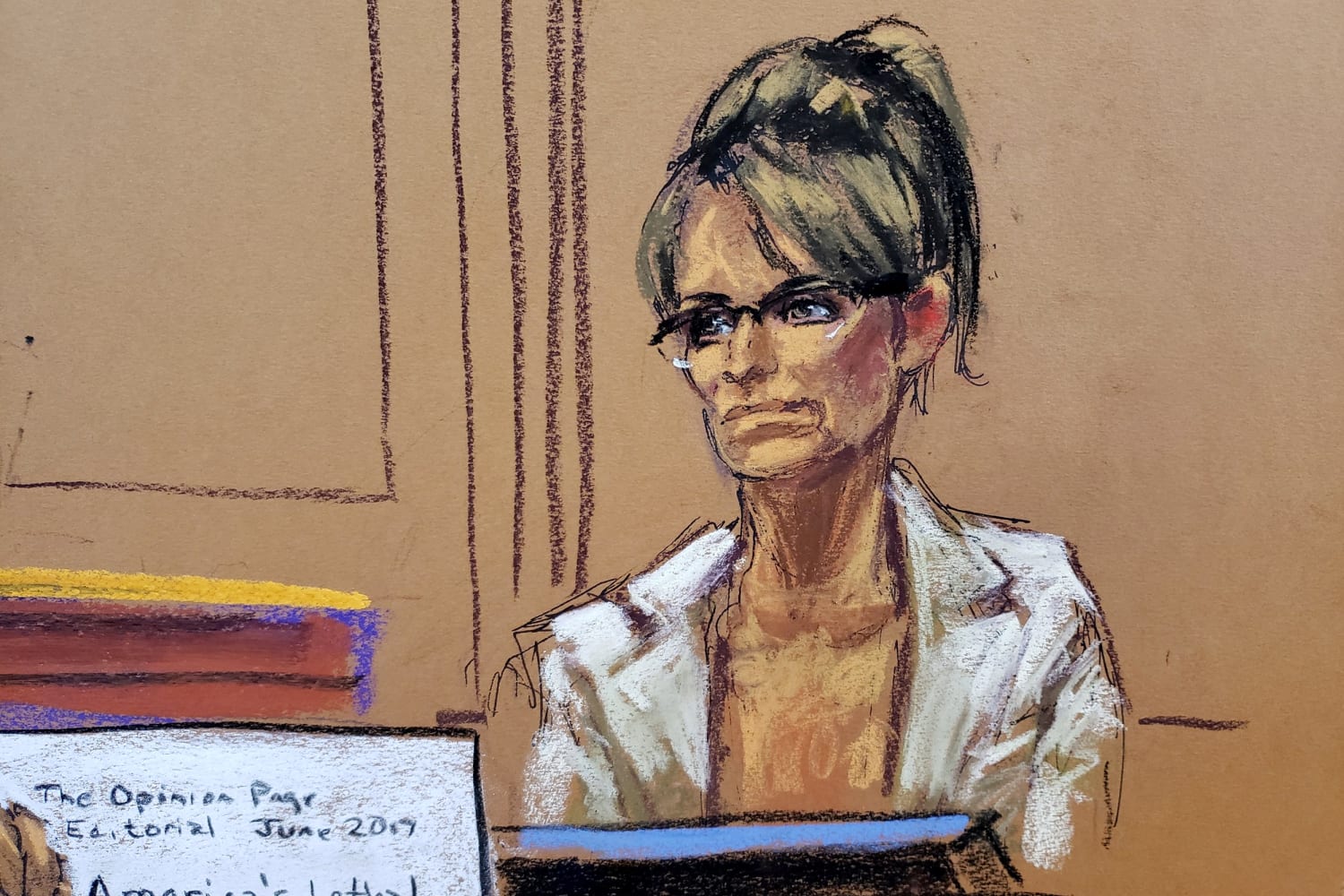

The one-time vice presidential candidate took her 2017 defamation case against The New York Times all the way from complaint to trial to surviving a dismissal to jury deliberations. Then on Monday, just like that, Judge Jed S. Rakoff granted the Times’ motion for a judgment against Palin. The wild part is: The jury was still deliberating when he ruled. So Palin lost — and then she lost again when the jury came in with its decision Tuesday.

Palin probably feels like Rakoff put his judicial thumb on the scale in favor of the Times. But it’s more complicated than that.

Based on her statements in front of the courthouse, Palin seems to see this as a biased, intervening judge who was determined to deny her a jury trial, one way or another. And the fact that Rakoff — appointed by Democratic President Bill Clinton — already threw her case out once probably only adds to her sense of grievance. The libel case was revived by a federal appeals court that sent it back down to Rakoff for trial. Now it seems to her that the judge found a way to dismiss her case once again.

It’s not uncommon for litigants to feel like a judge has something against them. I admit: As a defense attorney, I often have. Nearly all lawyers do at one point or another. Sometimes I’m right. But most of the time I’m probably wrong — and paranoid.

Palin probably feels like Rakoff put his judicial thumb on the scale in favor of the Times. But it’s more complicated than that. While sometimes judges are biased in favor of one party, the nuances of the rules of procedure in the Palin case tell a different story — not that Palin will be convinced otherwise.

Under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 50, as long as Palin had a full opportunity to provide evidence to prove an issue during trial, if the court determines that the evidence she did provide wasn’t enough for the jury to find in her favor, the court may grant a motion from the opposing side for judgment “as a matter of law.” In other words, the judge can decide that issue on his or her own regardless of what the jury thinks.

Rakoff has said such motions should not be granted unless “there is such a complete absence of evidence supporting the verdict that the jury’s findings could only have been the result of sheer surmise and conjecture,” or “there is such an overwhelming amount of evidence in favor of the movant that reasonable and fair minded [persons] could not arrive at a verdict against [it].” In other words, it’s hard to win one of these motions.

But Rakoff concluded that Palin failed to present enough evidence that then-Times editor James Bennet met the legal standard for libeling a public figure, that is, that he acted with “actual malice” — that he knew there was a high probability that the published statements were false and that he recklessly disregarded that high probability. To Rakoff, the fact that Bennet sent his edits to a colleague, Elizabeth Williamson, with instructions to “please take a look,” undermined Palin’s position that he acted with the requisite “malice” to such an extent that it would be wrong for a jury to interpret it otherwise.

Is it common for the defendants in a civil lawsuit to make this motion before the jury gets the case? Yes. In fact, it’s kind of mandatory. The Times could not ask the appeals court to overturn an unfavorable verdict unless the Times made a post-verdict motion for judgment as a matter of law. But that post-verdict motion is technically a renewal of a pre-verdict motion, which must be made before the jury gets the case. So, the Times had to make a pre-verdict motion in order to make a post-verdict motion in order to appeal. Whew.

But why grant this motion and still allow the jury to continue deliberating? Palin had lost. It was preordained. Why should the jury still have been kept away from their jobs and lives, laboring to return a verdict? Because Rakoff tried to create as complete a record as possible for appeal, explaining Monday that the appellate court “would greatly benefit from knowing how the jury would decide it.”

For now, the trial is over. But, on appeal, the appeals court could decide Rakoff was out of line in granting this motion. If that happens, then the appeals court could choose to just reinstate the jury’s verdict instead of sending it back to the lower court for (another) trial.

The judge may also be thinking even further ahead, to a Supreme Court appeal. A verdict adds more information to the appellate record, and it’s generally harder to overturn a jury’s verdict than a judge’s decision dismissing a case. Appeals courts rarely disturb jury verdicts, and they give a high degree of deference to the jury’s evaluation of witnesses.

On the other hand, under the standard applied to a review of “matter of law” judgments like Rakoff’s, the appeals court would look at the matter anew, as though it had come to the court for the first time rather than provide any deference to Rakoff’s decision.

The current Supreme Court might be more receptive to Palin’s argument. Justice Clarence Thomas, for one, has called for the Supreme Court to revisit a previous libel case that set the high legal bar that makes it so difficult for Palin to win her case now, coincidentally also involving The New York Times. In that 1964 suit, New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, as well as the cases that came after, the court established an exacting burden that requires a public figure like Palin to prove that the Times acted with aforementioned “actual malice” in recklessly disregarding the high probability that its published statements were false and didn’t merely publish untrue information about her.

On the other hand, the Sullivan standard has been around, and relied upon, for decades. The news is an essential part of our constitutional fabric. Scrapping Sullivan could seriously hinder freedom of the press, and it’s not clear that the entire conservative wing of the court wants to follow Thomas’ lead.

Could Palin still eke out a win on appeal? Possibly. But not today. For her, the battle is already lost. The jury just never knew it.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com