The prosecutors working on the Capitol riot cases have gotten a plum assignment. Sure, it’s a lot of labor on the front end, sifting through gigabytes of images and video evidence. But it’s not as if they’re spending time chasing down dead ends or tracing missing witnesses. Almost all of the digital footage they are poring over is helpful to their cases against the rioters. The challenge lies more in organizing all the damning evidence, not finding it. And the best part for these prosecutors? A lot of the incriminating evidence came from the rioters themselves — and keeps on coming.

They used selfie sticks to publish their conduct on social media, or at least send it to friends (in one case, to a federal agent — oops).

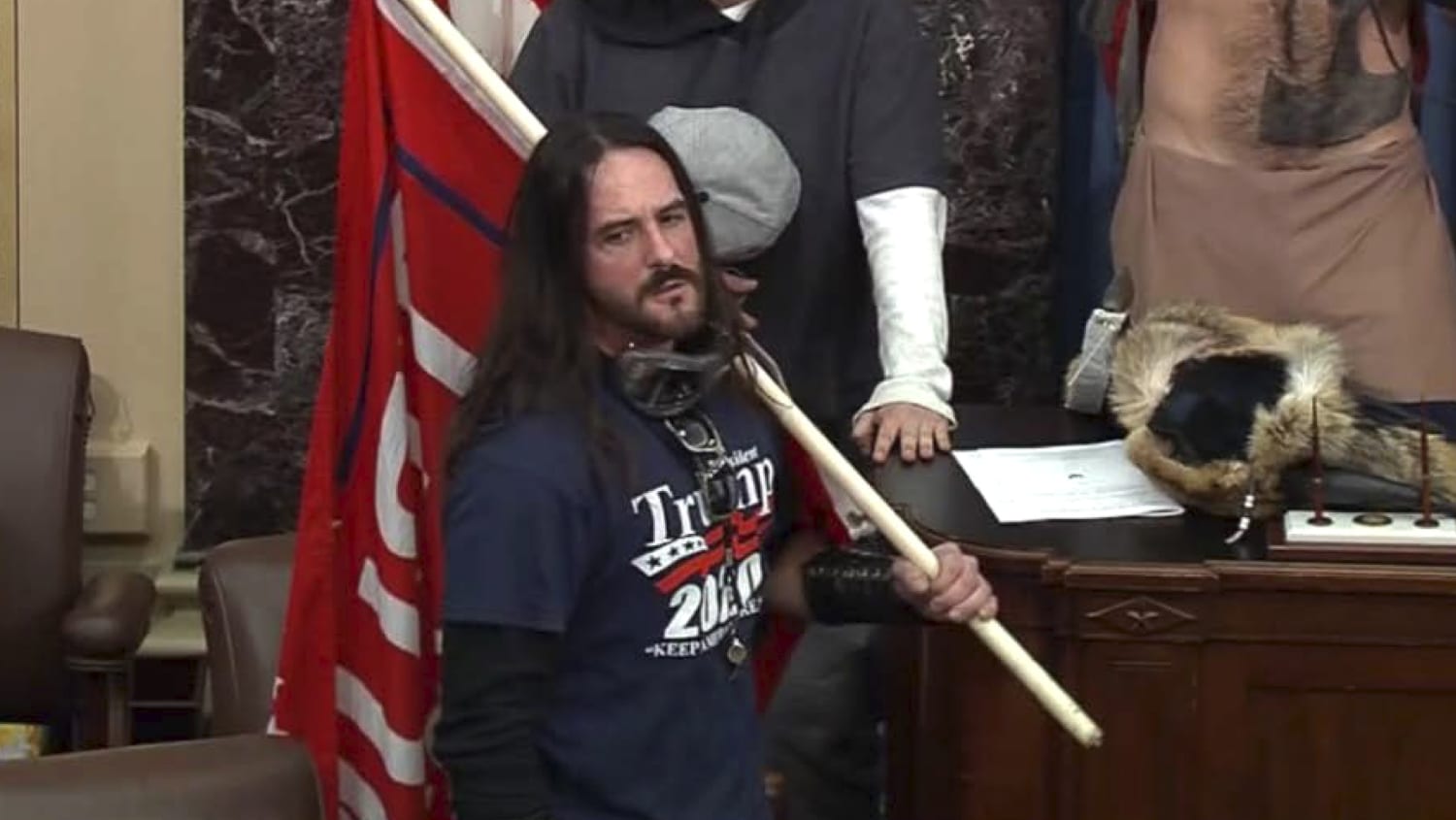

On Tuesday, Dona Sue Bissey was sentenced to 14 days in jail after she wrote that Jan. 6 was the “best f—— day ever” in a Facebook post. In July, Paul Hodgkins was given eight months in prison after footage showed him on the Senate floor. And Brandon Fellows, a 27-year-old Capitol demonstrator representing himself in court, inadvertently admitted to additional crimes at a bond hearing this week.

Master criminals these insurrection defendants are not. Anyone who grew up watching the mob movies of the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s would have a hard time imagining the gangster characters of “The Godfather” or “Goodfellas” posting videos of their heists to Instagram or making TikToks out of bank robberies. Longer ago, before the internet had even been invented, insurrectionists in other countries were wearing balaclavas to hide their faces.

Not the Capitol rioters. They used selfie sticks to publish their conduct on social media, or at least send it to friends (in one case, to a federal agent — oops). By doing so, they also unwittingly added everyone in the background of their shot to the police dragnet.

For federal prosecutors, sorting through all this material is the equivalent of digging through evidentiary treasure chests. It’s not just an opportunity to advance their careers at the Justice Department; it’s a chance to be a part of American history, without the huge dangers associated with trying to convict the Mafia — or the risk of an O.J. Simpson-like acquittal.

Indeed, the defense attorneys won’t be able to do much to stand in the way. Many, if not most, of these defendants may be eligible to be represented by a public defender. But with so many defendants involved in the same incident, the public defender often has conflicts in representing all of them, since they may point fingers at each other. So some defense attorneys are appointed from what’s called the Criminal Justice Act Panel — volunteer, private attorneys blindly appointed by the court who accept the government’s bare-bones minimum hourly rate.

Several of these defense attorneys, however, are being relegated to the position of coach instead of participant. That’s because some of these defendants have elected to forgo defense attorneys and proceed pro se — representing themselves — in court.

Pro se defendants occupy hallowed ground in our Constitution. In 1961, Clarence Earl Gideon was accused of breaking into a pool hall and stealing $5 in change and a few bottles of beer and soda. He was denied court-appointed counsel, since at the time the state didn’t have to provide it, and was convicted. In 1962, he submitted a pro se handwritten petition to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court ruled that the 14th Amendment required the “assistance of counsel is a fundamental right essential to a fair trial.” This became the famous case of Gideon v. Wainwright and the basis for the film “Gideon’s Trumpet.”

Judges will publicly state that defendants have a fundamental right to proceed pro se in a criminal case. But privately, if those judges are being honest, they will probably say pro se defendants are an unmitigated disaster of circus-like proportions. A judge will warn a defendant against it, and then, if the defendant persists, at least try to appoint an attorney to advise the defendant. Being appointed to an unreasonable client can be a nightmare for an attorney. But, when only advising, the lawyer instead gets paid to be a front-row spectator to the chaos.

Fellows is a perfect example. Despite the judge warning him at the outset of the hearing that what he might say could hurt his case, he still proceeded to incriminate himself. If a prosecutor wants to prosecute the crimes Fellows raised at his hearing, the entire investigation could consist of ordering the transcript from the court reporter, maybe accompanied by a thank-you to Fellows himself. Even he admitted “it was a stupid decision” to proceed pro se.

Brian Mock is another one. He’s accused of pushing two police officers to the ground during the riot. Mock allegedly wrote on Facebook about his bid to overthrow the U.S. government. Although Mock’s intended audience was not federal prosecutors, they eventually appreciated the post, along with innumerable posts by other Capitol defendants.

As is often the case with pro se defendants, Mock first claimed his public defender didn’t represent him properly. He told the court he wanted to represent himself; he had a plan to prove FBI misconduct and conspiracy in his defense. Although his conversations with his public defender are privileged, it’s a good bet the appointed attorney refused to be a part of this defense — leaving Mock to his own devices if he wanted to make the argument.

Pauline Bauer is another classic pro se defendant. She’s accused of just being a part of the mob in the Capitol, not committing violence. Yet she’s been in custody because she’s refused to comply with pretrial release conditions — rejecting the judge’s request that she check in with her pretrial officer once a week. She’s filed a 114-page nonsensical “motion” preserved on the electronic case filing system for eternity.

Prosecutors do get a little nervous about pro se defendants — mostly because the irregularities they cause can create appealable issues. An appellate court might then overturn a conviction because the chaos at trial violated some right of the defendant.

As for the pro se defendants themselves, are these folks Clarence Gideon? Are they following in the footsteps of the cherished pro se defendant who single-handedly expanded the reach of the 14th Amendment for all the accused who came after him? Probably not. In theory, they have the potential to change the legal system forever, but more likely they will just gum the system up while forestalling the most likely outcome: a conviction.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com