WASHINGTON — President Joe Biden wants to vaccinate teachers to speed school reopenings, but more than half the states aren’t listening and haven’t made educators a priority — highlighting the limited powers of the federal government, even during a devastating pandemic.

“I can’t set nationally who gets in line, when and first — that’s a decision the states make,” Biden said while touring a Pfizer plant in Michigan on Friday. “I can recommend.”

Under the Constitution, the powers of the federal government are far-reaching but not all-encompassing. States have always retained control over public health and safety, from policing crimes to controlling infectious disease, including distribution of coronavirus vaccines that Washington helped create and whose supply it controls.

That the U.S. has the world’s highest death toll from the pandemic has renewed criticism of the federalist system that has allowed the states to do as they please, with very different approaches and very different results.

“There’s a pretty strong argument that the confusion we’ve created has, in fact, cost human lives,” said Donald Kettl, a professor at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas and author of “The Divided States of America: Why Federalism Doesn’t Work.” “We pay a pretty high price sometimes for letting states go their own way.”

He added: “The founders were very conscious of the fact that it was a collection of states that had succeeded in winning the Revolutionary War. If you roll that forward, you end up with this patchwork of different vaccine priorities, mask mandates and lockdown rules, because the federal government cannot force states to do things.”

The feds and the states have been in a near-constant tug-of-war for 230 years — sometimes violently, as during the Civil War — often refereed by the Supreme Court, which has ruled that it’s the states that have “the authority to provide for the public health, safety, and morals” of their residents.

The federal courts — not the federal government — have been able to exert their will over the states on issues from school desegregation to abortion to voting rights. But schools, abortion clinics and elections are still run or regulated by the states.

The federal government has spent the past two centuries trying to come up with creative ways to push its agenda on the states, sometimes by dangling the promise of federal funding as a carrot — and the threat to withhold it as a stick.

For instance, to build the Interstate highway system, the feds promised to foot 90 percent of the bill if states put up just 10 percent. The catch was that the roads had to abide by regulations that started small — bridges needed to be tall enough to allow tanks to pass under, to cite one requirement — but quickly grew to encompass the nationally uniform system of roads we take for granted today.

During the oil crisis of the 1970s, when gas prices skyrocketed amid tensions in the Middle East, Congress wanted Americans to slow down to conserve fuel. But it couldn’t institute a national speed limit, so lawmakers tried to compel the states do it, passing a law to withhold highway funding from states that didn’t set the maximum speed limit at 55 mph. (Congress repealed the law in 1995.)

Washington pulled a similar move in 1984, when it forced states to raise the drinking age to 21 if they wanted highway money.

But just as often, the courts have pushed back against what they view as Washington overreach.

“When you boil it down, the delivery of public health interventions resides, really, at the state and local level,” said Josh Michaud, associate director for global health policy at the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation. “That’s been the model since very early on in our republic.”

The Affordable Care Act is a hodgepodge of incentives and mandates because, in part, it was built to comply with the complexities of American federalism, by, for example, giving states the responsibility to set up their own insurance exchanges.

The Supreme Court nearly killed the law for unconstitutionally coercing states to expand their Medicaid programs. The court found a workaround, like the highway funding trick, in which the Medicaid expansion became a federal incentive, instead of a federal mandate. But 12 states have still legally refused to join the expansion.

When it comes to fighting infectious diseases, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides guidance on health issues to states, which delegate much of their authority even further to counties and municipalities.

“In the positive sense, this means the system can be responsive to local conditions based upon the people who know them best,” Michaud said. “But it also leaves open the possibility for inequality and greater risk from the virus because of the lack of a coordinated and effective response.”

Last year, South Dakota defied federal guidelines against mass gatherings to allow a massive motorcycle rally to proceed. It has since been linked to more than 250,000 coronavirus infections around the country.

During the 1918 influenza pandemic, Philadelphia allowed a massive parade to proceed and its death toll surpassed 10,000, while St. Louis banned mass gatherings and kept its death toll below 700. Washington played little role in that pandemic — the CDC wasn’t even formed until 1946 — and President Woodrow Wilson never made a public statement about the virus, which killed more than 650,000 people in the U.S.

Today, states can institute mask mandates, but many questioned the constitutionality of Biden’s proposed national mandate. He ended up, instead, issuing mask mandates for federal property and interstate travel, like planes and buses, over which the courts have long ruled that the feds have authority.

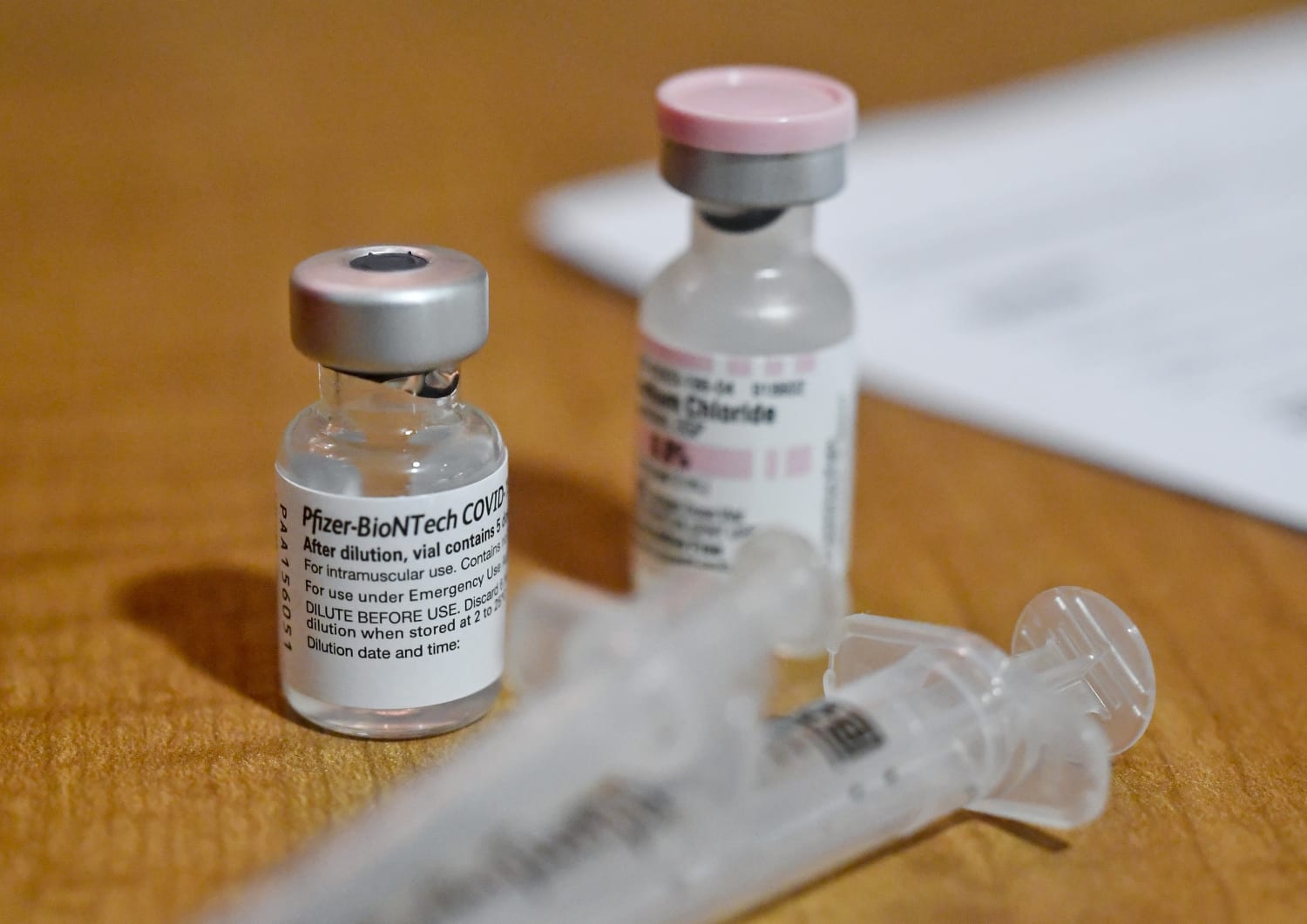

The CDC legally can’t force states to roll out Covid-19 vaccinations with any particular priority, said Sarah Gordon, an assistant professor of health law and policy at Boston University.

“They are actually quite limited in what they can do,” Gordon said. “The federalist separation of national versus local public health authority in the U.S. has, repeatedly, hamstrung rapid and effective pandemic response.”

In theory, Biden could cut vaccine supplies to states, which former President Donald Trump threatened to do in response to criticism from New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, but it would cause an uproar, and the new administration has, instead, chosen a simple formula of allotment based on each state’s adult population. And it can set up its own vaccination centers in regions with eligible populations it’s trying to target.

But even some Democratic governors have chosen to ignore federal guidelines and set their own vaccination priorities.

The CDC calls for vaccinating all essential workers, including teachers, before moving on to those under 75. But several states have chosen to vaccinate people over 65 and those with pre-existing conditions first.

“We are going to rely on the CDC definition of an essential worker. But that’s a lot of people, including teachers,” Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont told the Hartford Courant’s editorial board. “I’m not sure you move grandma to the back of the line so you can move [teachers] forward.”

Jon Valant, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who studies education policy, said Biden’s most effective tool to push states to vaccinate teachers might be the bully pulpit.

“What the federal government can do is mostly a combination of guidance, cover and pressure,” he said. “Teachers unions can be a lightning rod, and if you’re prioritizing teachers because the CDC or the federal government says to, it helps to protect you from critiques.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com