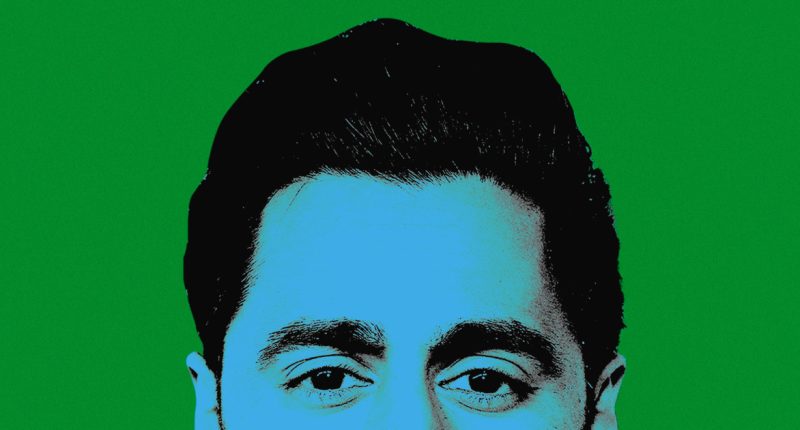

After stand-up comedian Hasan Minhaj said he fabricated routines about the racial and political injustices Muslim and Indian Americans face, some comedians and experts say he’s done a disservice to the South Asian diaspora and Muslim Americans.

Many are saying they are worried Minhaj’s fabrications could invalidate people’s accounts of actual racism and Islamophobia.

“There’s so much anti-immigrant sentiment out there. People can stereotype and say, ‘Oh, look, that South Asian comedian lied. We can’t believe anything these people say,’” said Lakshmi Srinivas, an associate professor of Asian American studies at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

Others, however, understand the criticism but think the whole thing has been blown out of proportion.

The New Yorker published an in-depth interview on Friday detailing several stories and experiences that Minhaj admitted to fabricating and using in his Netflix comedy specials “Hasan Minhaj: Homecoming King” and “Hasan Minhaj: The King’s Jester.”

For more from NBC Asian America, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Minhaj, who previously shared the story of his daughter’s potential exposure to anthrax after opening a hate letter addressed to him during his comedy special and in an interview with NBC News, told The New Yorker that his daughter had never been exposed to a white powder.

The outlet reported that Minhaj said the account was inspired by an interaction with his wife instead. He said he opened the envelope sent to his home and asked his wife, “What if this was anthrax?”

Minhaj also said he fabricated the story of being surveilled by a white FBI informant named Brother Eric, who began attending his mosque. Instead, the outlet wrote that he said it was inspired by a basketball game he played as a teenager, in which he and his friends suspected the white men they were playing with were law enforcement officers.

And the story of his high school crush, a white girl who rejected him moments before the prom, was not true, he said, according to the article. The fabricated anecdote, which was the central premise of his 2017 Netflix special, “Homecoming King,” ended with Minhaj learning that her family did not want their daughter to be seen with a South Asian boy.

Srinivas said Minhaj is more than just a comedian, which is why he’s facing more backlash. He shared personal stories during his specials, which he marketed as autobiographical.

“He seems to think it’s creative storytelling — that’s how he seems to present it. But he also wants to be known as someone who speaks on social justice issues and who is on the side of the oppressed,” the associate professor said.

Srinivas believes viewers and fans likely feel betrayed by Minhaj, whose stories often focus on racism, xenophobia and Islamophobia.

“He’s not just trying to entertain people. He wants to be seen as someone who’s speaking to social justice issues. He has this moral platform,” she said. “He is feeding them these stories, working up their sense of moral outrage and not giving them an inkling that they are not based on fact.”

In a statement to The Hollywood Reporter after The New Yorker article was published, Minhaj said all of his stand-up stories are based on events that happened to him, but said he used the “tools of standup comedy — hyperbole, changing names and locations, and compressing timelines to tell entertaining stories,” the outlet reported.

“You wouldn’t go to a haunted house and say ‘Why are these people lying to me?’ — The point is the ride. Standup is the same,” he said, as quoted by THR.

Representatives for Minhaj did not respond to NBC News’ request for comment.

For comedians like Sarah Suzuki Harvard, who is a Muslim American, Minhaj was a role model. She said his use of race and religion in his comedy routines was empowering and inspired some of her material, making the news even more disappointing.

Harvard said she understands why Minhaj is facing intense scrutiny for his decision to exaggerate his stories.

“They trusted him. That’s why I think people are upset, and it makes sense why there’s backlash,” she said. “A lot of people trusted Hasan Minhaj. They trusted his programs because he depicted himself as a journalist, truth-teller, and someone who would always speak to what’s right, and he completely destroyed that.”

Harvard said it was frustrating to see Minhaj assume the traumatic experiences other Muslim Americans and the South Asian diaspora faced instead of uplifting those who endured those experiences.

“There are so many stories of real-life people who went through trauma, who went through Islamophobia, who went through assault and harassment and issues of systemic violence. For me to see someone like him lie and make it seem like it’s about himself was gross,” she said.

Vishal Kalyanasundaram, a South Asian comedian, said he can understand the backlash but believes it shouldn’t be such a big deal.

“I think this will blow over and it’ll be fine. I think we all need to look at this as more of, ‘Hey, it’s not like the worst thing that anyone has ever done, but maybe it’s a thing that we should all be better about not doing and we should all wag a finger at it.’”

Kalyanasundaram said expecting Minhaj to be the perfect role model is unreasonable.

“We are holding our own people to such a high standard of perfection — an impossible standard of perfectionism, and white people cross that line every day,” he said. “Just because he’s South Asian doesn’t mean he’s the golden child and the voice for our people. He’s a human. He’s allowed to have flaws. He’s allowed to make mistakes.”

Kalyanasundaram urged that this should instead be a learning opportunity.

“I think we’re all too quick to punish people and condemn them instead of looking at this collectively, as what can we learn from this and how can we move forward,” he said.

Nylah Burton, a freelance journalist, also defended Minhaj, recognizing that the comedy industry is difficult to break into, especially for a South Asian Muslim comedian.

“Would white people have given him these opportunities if his stories were just about being an average brown Muslim kid in the suburbs? No. Would they have kept tuning in to listen to him talk about Islamophobia without proof his life had been threatened by it? No,” she wrote on X, formerly known as Twitter.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com