Deion Sanders’ Colorado Buffaloes did not make it to Pac 12 championship on Friday; they lost their last six games. Sanders’ star quarterback, his son Shedeur Sanders, did not finish the season because of an injury. Three top recruits decommitted from joining the program. A coach quit and at least one player entered the transfer portal.

So why is Boulder, Colorado’s notoriously thin air thick with optimism? And why did Sanders become such an enormous deal in the first place?

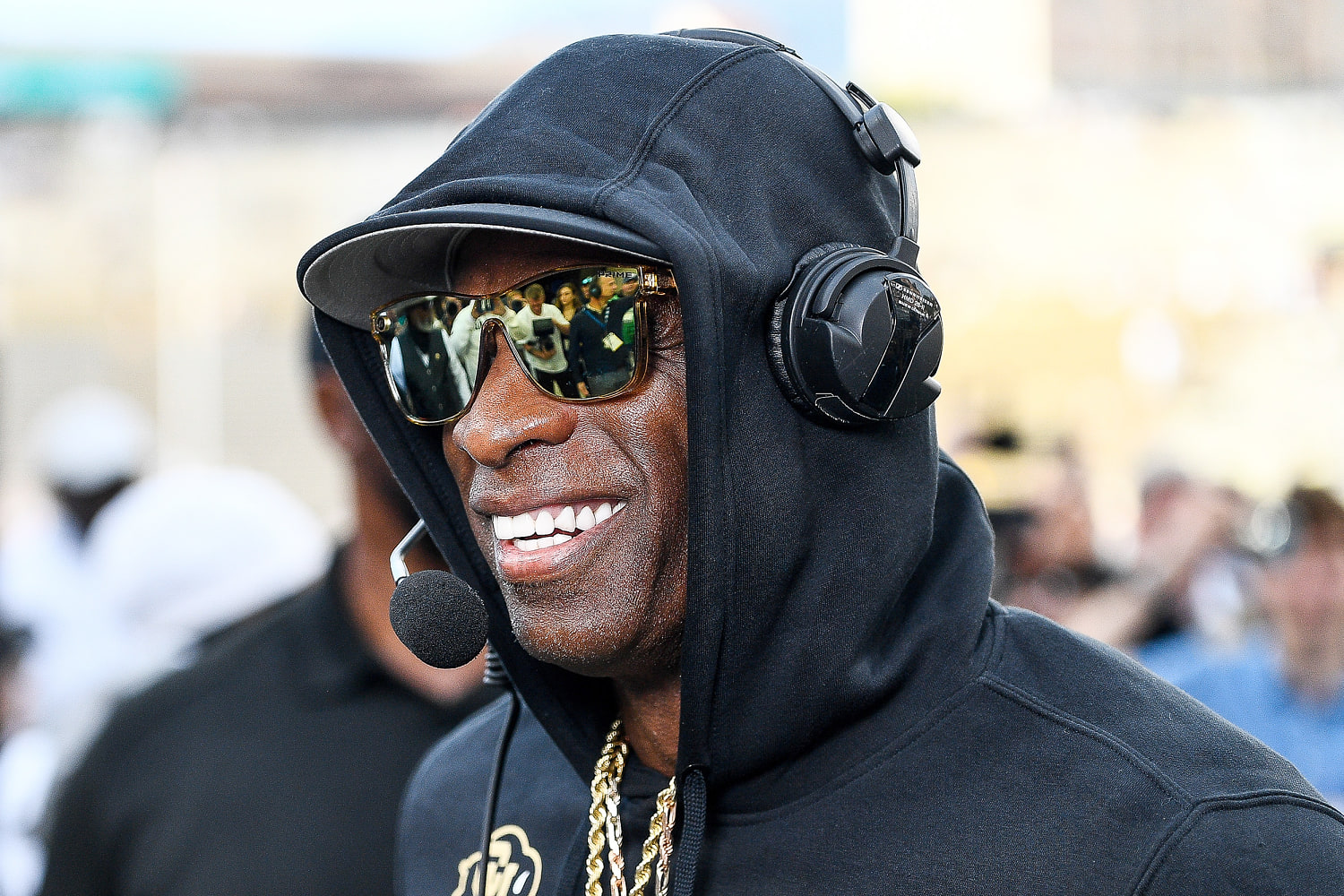

The answers are many and they are all about Sanders, 56, an all-time NFL great whose confluence of audacity, tenderness and introspection — played out to millions on social media — inspired a legion of followers, countless of them with faint interest in college football until he took over in Boulder. His influence has been so palpable this season that Sports Illustrated named him “Sportsperson of the Year” on Thursday, a nod to his impact beyond the games, as the end of the season did not match the beginning.

Despite all that did not go right in his first season after controversially leaving Jackson State University, a historically Black school, Black fans in particular have rallied around “Coach Prime.” He high-stepped into Boulder, a city with a population of just 1.3% Black people, reinvigorated a downtrodden fan base and built a national coalition of support.

“When it was announced Deion was being hired, it’s like the company that hadn’t shown much effort toward diversity doing something really cool,” said Ellen Brandon Calhoun, a 1990 graduate of the university and executive at Disney in Orlando. “So I was really excited about that. The school has changed dramatically since I was there, but the diversity story has not changed.”

Calhoun said there were about 200 Black students — among 23,000 students — during her four years at the University of Colorado; that’s less than 1%. Now, of the 37,00 students at Colorado, just 2.7% or 1,003 are Black.

In 2017, National Geographic called Boulder “The happiest place in the United States.” That distinction was disputed in the 2023 documentary, “This is (Not) Who We Are.” Its tagline reads: “The happiest place in America. . . said no Black person ever.”

“There was all this racial profiling by police; athletes were being harassed,” Calhoun said. “Not saying there was this intense Southern racial environment, but race was an issue for sure. So to do something like hiring Deion is so decisively Black culture. He’s become an icon in Black culture. He represents more than excellence in his sport. So, in general, we cheer for Black excellence anywhere, but especially where it hasn’t been before, like in Boulder.”

Sanders’ magnetism — his inspirational monologues, direct addressing of racism and reinforcement of parental values — “makes you want to support him and the Buffaloes,” Calhoun said. “You want to be in it. That is the appeal of what Deion has brought. And we embrace him and adore his focus on parenting and fatherhood and raising young men. You put that with his arrogance and bravado and it’s super compelling.”

During a Sept. 16 game, Sanders used the sleeve of his hoodie to wipe Shedeur’s face. He also ran along the sideline as his other son, Shilo, a linebacker also on the team, returned an interception for a touchdown.

“I coach, but every now and then during the game, I have a dad moment,” Sanders said.

And that’s where Sanders’ true power lies, where he connects with Black people, according to Christopher K. Bass, a forensic psychologist and associate professor at Clark Atlanta University. Bass said “it makes sense” to him that Sanders has garnered national support from the Black community because, “as a Black man in sports, he stands for something we typically don’t see. He gives it to his players hard but he gives it with love. Depictions of the Black male’s affection are absent; you typically don’t see that. Black men are supposed to be non-feeling, all business. So, when he goes up and he hugs his players, when he loves on his players, it represents what we all know as a community: that Black men do love on their children. So it goes well beyond the football field.”

Colorado, which had one victory all last season, won its first three games, thrilling its expanding fanbase. From a football standpoint, his team lacked size on the offensive and defensive fronts, and that vulnerability was a significant reason the team finished the season 4-8.

But even that disappointing end has not quelled the connection Sanders has built — unwittingly or not — with the team’s supporters, Bass said. “He represents something a little bit bigger for those of us who seek out sports for some type of relief from or escape from the daily grind,” he said. “With Deion, not only can we escape from our present reality, but we can see ourselves represented in a way that actually goes beyond our own abilities.”

He likened the connection of Sanders to the Obamas.

“We felt connected to that family, like we were related to them,” Bass said. “So when one does well, we all feel like we’re riding on that same train.”

This season, Sanders “represented a joy, a power, a strength of bravado that just sort of trickles down into who we see ourselves personally,” Bass added.

The Buffaloes sold out every home game this season in their stadium that seats 50,183. The year before he arrived, the average attendance of home games was 26,891. A ticket to a Colorado game has become a hot commodity.

Yemane Gebre-Michael, whose four siblings graduated from Colorado, attended two games this season — his first in 27 years living in Denver, about 35 minutes away.

“Oh, I had to go,” he said, “because this man galvanized an entire state. It has been a polarizing three, four years for us out here with Covid and you go places and you see Trump supporters. The political environment has just been nasty. And he and his team have become something that kind of brought people together and are something we enjoy in common versus something that we fight over.”

The Denver Nuggets won their first NBA championship in June “and we were happy and celebrated,” Gebre-Michael said. “But they are second fiddle to Deion. Think about that. I have friends texting me from all over the country about getting them tickets to a Buffalo game.”

Derrick and Kim Bell of Atlanta traveled to Boulder for the University of Southern California game against Colorado at the end of September. It was a prime opportunity to connect with their daughter, Kennedy, a freshman at USC, who flew in from Los Angeles.

They chose Boulder to rendezvous because they “wanted to witness firsthand Deion’s impact on college football, the school, the city,” Derrick Bell said. But what he found, surprisingly, was a sense of community, even though the area lacks a large Black population.

“There aren’t many Black people at all in that town,” he said. “I don’t know if they shipped us in or what, but there definitely were a lot of Black people at the game. His persona draws you in. And Black folks want to see him succeed. He’s straightforward. He doesn’t mince words and he’s unapologetic. And maybe white folks don’t want to see him succeed to maybe humble him. Not making it a race thing, but that’s the sentiment.”

The white Sanders detractors are evident, Gebre-Michael said. “It’s palpable. You could see it, feel it. After the first three games, he got so high up on the pedestal. They want to see you fall. It’s typical of our society. They pump you up to be up there, and boy, they can’t wait for you to get knocked down. They want us to be humble. They want us to be meek and be grateful. And that’s not Deion. And that matters to us.”

That defiance as a Black man with a national platform endears Sanders to the community, whether he’s trying to or not. “Here we have a brother who is not bending,” Bass, the psychologist, said. “He’s become an archetype for the hero in Black America today, which is what everybody wants. We want to root for something bigger than ourselves, because he represents all of us. Deion has made that leap, that connection—and for Black people, that’s a big deal.”

For more from NBC BLK, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com