Childhood obesity rates continue to rise in the U.S., affecting nearly 1 in 5 kids and adolescents ages 2 to 19.

To combat it, experts are calling for early and intensive treatment. For some children, that may include weight loss medications.

The American Academy of Pediatrics included anti-obesity drugs for the first time this year in its guidelines for treating childhood obesity. According to the guidelines, pediatricians should offer weight loss drugs to adolescents ages 12 and up with obesity, alongside diet and lifestyle changes that encourage healthy eating and exercise.

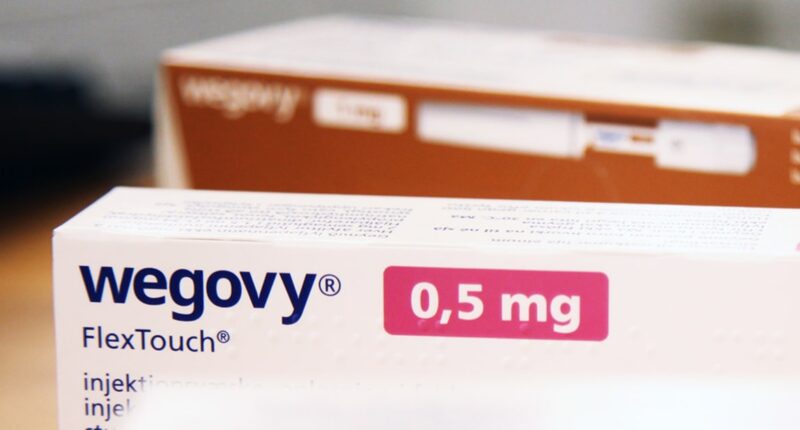

Four weight loss drugs are approved for use in adolescents as young as 12: Wegovy, Saxenda, orlistat and Qsymia. Wegovy and Saxenda are part of a newer class of drugs called GLP-1 agonists that have soared in popularity in the past year.

The recommendations were immediately met with controversy, especially from groups concerned about eating disorders, who worried that including weight loss drugs would ultimately be harmful to children.

The drugs — though highly effective for weight loss — do come with drawbacks: They’re pricey and not always covered by insurance, and experts believe people taking them will need to be on them long-term.

Here’s what parents and adolescents should know about weight loss drugs.

How long do teens need to be on weight loss drugs?

Doctors who treat obesity in children say one of the most common questions they get from parents is how long will their child need to be on a weight loss drug.

For GLP-1 agonist drugs like Wegovy, there’s a growing consensus among experts that adults will need to be on them long-term to maintain their weight; indeed, studies have found that when people who have had success with the drugs go off them, many gain weight back.

“We don’t really have data about this in adolescents yet,” said Dr. Emily Breidbart, a pediatric endocrinologist at NYU Langone Health in New York City. “But we generally counsel families that this is a long-term treatment.”

Breidbart said drugs to treat obesity should be thought of similarly to other medications for other chronic diseases, like high blood pressure or high cholesterol, which need to be taken long-term to maintain results.

“Say you’re taking a statin for high cholesterol — we know that once you come off that, your cholesterol is going to go back up,” she said.

More on weight loss drugs

But there’s a difference between putting older adults on a drug for the rest of their lives compared to children, said Dr. David Ludwig, a pediatric endocrinologist at Boston Children’s Hospital. Ludwig said that the drugs are an “exciting” new part of the arsenal against obesity but that he has concerns about the unknown long-term effects of starting them so young.

“If you’re starting a drug and somebody’s age 60, maybe you’ve got a few decades of treatment in front of you,” Ludwig said. “But for a child with a lifetime of treatment, the risks are much greater.”

Dr. Alaina Vidmar, a pediatric endocrinologist and the medical director of the healthy weight clinic at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, said that more data is needed on the long-term effects of starting the drugs early but that ultimately, the potential risks will need to be weighed against the long-term risks of obesity.

“I think while we do need to learn more about what it means to be on an obesity medication for 60 years, we know quite a bit about what it means to live in a larger body for 60 years,” Vidmar said. “We have to weigh the risks of doing nothing to the risk of doing the best we can with the tools we have right now.”

When should my child start weight loss medication?

The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines say physicians should offer the drugs to children with obesity ages 12 and up. But experts say that even with that guidance, there’s no magic age or weight for when a child should start on weight loss drugs.

“We’re all in some ways kind of figuring this out as these new drugs have come up,” Vidmar said. “I think most pediatric endocrinologists or obesity specialists are navigating how to integrate this into practice and the algorithm for how I treat kids.”

Whether to recommend the a weight-loss drug depends on the severity of the case and whether a child’s weight is starting to affect his or her health in other ways, experts say.

Unlike obesity in adults, which is generally classified as a body mass index of 30 or above, there’s no single BMI cutoff for growing kids; a BMI that falls in the obese range for a 12-year-old boy may not be considered obese for a 16-year-old. For childhood obesity, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines three classifications that pediatricians use to help guide their treatment.

The CDC ranks childhood obesity from Class I to Class III, with Class III associated with the most health complications. The guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics don’t specify a greater urgency to start patients on medications if they fall into one of the higher classes of obesity.

However, doctors who treat pediatric obesity often take the classes into account.

“We know that the risk of developing things like Type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart disease goes up as the class of obesity goes up,” Vidmar said. “I think a lot of clinicians will look at a child who has Class I obesity with no comorbidities differently than they might approach a child who has Class III obesity with pre-diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol.”

Those comorbidities, she added, would make one more likely to recommend anti-obesity drugs.

Breidbart said obesity-related issues such as sleep apnea or joint pain could make her more inclined to offer the medications, particularly to those who haven’t been successful with other weight-loss approaches, like diet and exercise.

If my child is on a weight loss drug, what about diet and exercise?

Eating a healthy diet and getting adequate exercise is imperative, even when you’re taking medications for weight loss.

Ludwig, of Boston Children’s, noted that while the drugs are effective, they won’t necessarily cause a person with severe obesity to lose all of the excess weight he or she needs to lose.

The drugs are “not going to completely cure obesity, as they produce about 15% weight loss,” Ludwig said. “That’s great, but many patients that show up at our obesity clinic have much more than 15% excess weight. They may have 50% or in some cases 100% or more excess weight.”

In an editorial published in May in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Ludwig criticized the AAP guidelines for not putting enough emphasis on diet. He proposed combining a low carbohydrate diet with a potentially lower dose of weight loss drugs.

“Maybe you’ll get fewer side effects, you don’t have to pay as much for the drug, and the long-term risks are lower,” he said.

Will these drugs promote eating disorders?

The AAP’s decision to include weight loss drugs in its guidelines prompted criticism from groups focused on treating and preventing eating disorders, already estimated to affect 20% of kids.

The Collaborative of Eating Disorder Organizations, which represents nearly two dozen groups, said in an open letter to the AAP that the use of weight loss drugs in this young population “will contribute to an increase in eating disorders,” citing an increased risk of eating disorders among youths who take over-the-counter diet pills and reports of doctors prescribing the medications to adults inappropriately.

Breidbart acknowledged that that is certainly a concern and part of the reason she prefers to use the drugs only in extreme cases.

“I do think that this is a really understudied issue,” she said, referring to how the drugs could promote unhealthy habits. “That’s why, in general, in my practice we’ve been using these drugs for severe obesity, especially with comorbidities.”

Breidbart plans to start using a new questionnaire that would screen all children for eating disorders before they start weight loss drugs. An eating disorder would make her more hesitant to start a child on weight loss medication.

In her practice, Vidmar emphasizes to patients and families that obesity is a chronic disease.

“In our clinic we have a strong focus on the fact that this is a chronic disease and no one’s fault,” she said. “Our goal of care is never about a number on the scale or the size of the body but that we are trying to reduce risk and life-limiting complications.”

What are the side effects of weight loss drugs?

Though effective, the new class of weight loss drugs has gotten a lot of attention for its side effects, which can include upset stomach, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Sometimes, the side effects will lead people to stop using the drugs.

Ludwig said the side effects are actually a direct result of how the drugs work — by slowing how quickly the body digests food.

“The food stays in the stomach too long, so people develop nausea and vomiting,” he said.

Still, Ludwig said, the side effects pale in comparison to previous generations of weight loss drugs and weight loss surgery.

“We do have studies, and we know that over the course of a year or two these drugs are safe and safer than the prior alternatives,” he said, adding that he’s keeping a close eye on any additional side effects that arise from longer-term use.

But Ludwig and others are keeping close eyes on side effects to come from more longer-term studies, especially in this age group.

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com