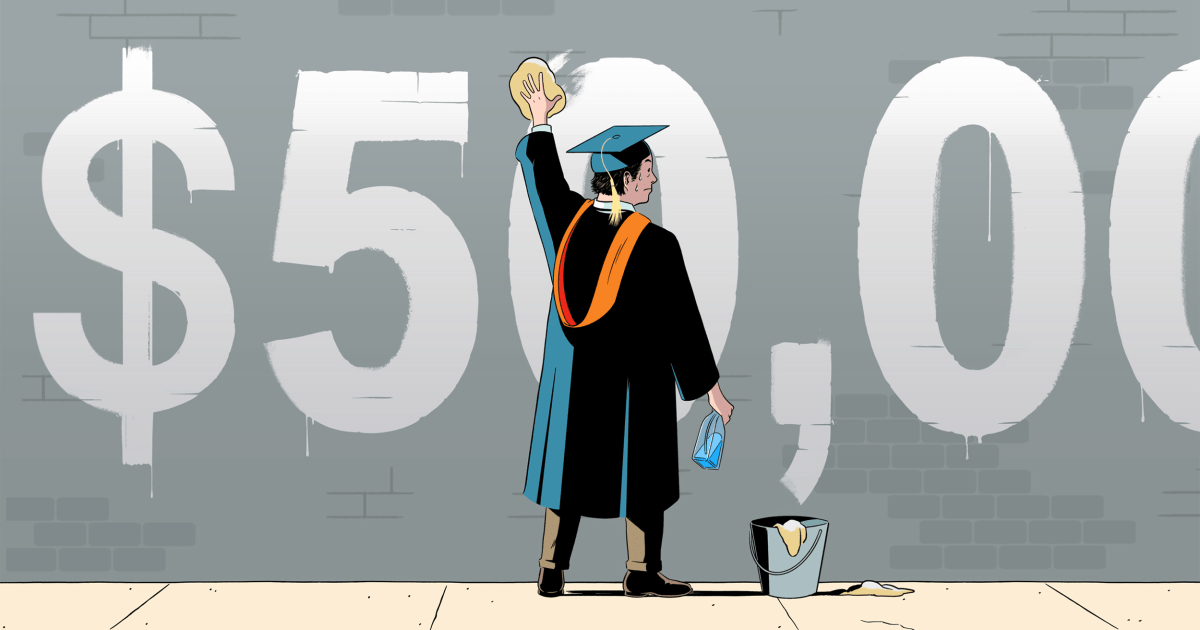

Around 43 million Americans owe $1.5 trillion in federal student loan debt, an enormous number with broad economic implications.

Student debt has been shown to hamper small-business growth, prevent young families from buying homes, delay marriages and inhibit people from saving for retirement.

Emotionally, too, the effects are wide-ranging. A 2017 study showed students with debt are less likely to enter their desired profession, instead prioritizing loan payments. Adults report feeling depressed over their student loan debt at high rates. According to one survey, 1 in 15 student loan borrowers reported that they had considered suicide because of their debt.

But what would happen if it were all to disappear or some of it at least?

President Joe Biden pledged to cancel $10,000 in federal student debt on the campaign trail. Many of his party’s members want him to be more ambitious. In February, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y and dozens of members of the Senate and the House called on Biden to wipe out $50,000 in federal student debt for all borrowers.

Biden has said he doesn’t believe he has the authority to cancel that much debt. In April, his administration asked the Department of Education to draft a memo on legal issues surrounding debt cancellation. While student debt relief will likely be left out of his annual budget, experts say that’s probably because he is waiting for the report, not because cancellation is totally off the table. In the meantime, student debt is still affecting the lives of many people around the country.

NBC News spoke to people around the country about what student debt cancellation would mean for them. Below is a selection of their stories:

Steven Mewha

Steven Mewha, 36, grew up in a working-class Irish Scottish family in Philadelphia and is now a lawyer in Hawaii. His is a classic American success story, but it wasn’t without challenges — or debt.

He graduated from Temple University into a recession with around $40,000 worth of debt.

“I wanted to better my life, I wanted to rise up out of the working class.” Mewha said. “Sure, I could’ve stayed at home and not gone to college, work a $40,000-a-year job. But I wanted more.”

“I was laid off from my first real job,” he said. Then, he got a job managing a movie theater, and the interest from his loans just kept accruing. In addition to the student loans, he was also in sizable amount of credit card debt, which he described as the “unsung villain of college education.” He eventually decided to further his education and enrolled in law school.

To do that, though, he had to go into more debt. Despite working through law school and going to a state school, he now has around $190,000 in debt.

He is now working as a lawyer, but has to pay more than $1,200 monthly on his loans. That combined with the high cost of living in Hawaii, buying a house and having children don’t feel like a possibility before the age of 40.

“Forgiving $50,000 of student loan debt would absolutely boost the economy in ways that are very difficult to calculate,” he said. “I could live, really live — it would be a stimulus.”

Jess Gawrych and Arielle Atherley

Jess Gawrych and Arielle Atherley, both 28, met at Boston University and have been together ever since. After college, they both pursued master’s degrees at George Washington University, in Washington, D.C., where they now reside and work.

Combined, they have about $278,000 in student debt, and together their payments total around $900 a month.

Both Gawrych and Atherley are first-generation college students from immigrant families. It was so important to go to college that when they were 18, they weren’t necessarily thinking about what it was costing them. Gawrych says she now looks at graduate school as a mistake.

“10,000 dollars doesn’t feel like much to be honest,” Gawrych said. “Especially because of some of the interest on loans, that would barely scratch the surface.”

To get $100,000 wiped out would “help with a lot of the typical life things that people want,” Atherley said, such as marriage, a house, kids. With their loans in forbearance because of the pandemic, the couple was able to buy a car — something they couldn’t have done with the hefty monthly loan payments.

“I am trying to manage my expectations, but being able to save, even $100, $200, $300 a month, that would make a huge difference in the long term.”

Gladys Villegas-Ocampo

“I wouldn’t even begin to describe how grateful I would be if my debt was forgiven,” Gladys Villegas-Ocampo, of Florida, said.

Villegas-Ocampo, 39, who was born in Ecuador and came to the U.S. as a young child, says when the bills come every month — cars, rent, loans, insurance — she has to choose which to pay.

She originally enrolled in college sometime after high school but wasn’t able to complete her degree because she needed to work.

“I have lupus. I have to be seen by a doctor almost every week, those payments do add up,” Vilegas-Ocampo said.

This year, the now-married mother of one will graduate after returning to finish her degree, hoping that she’ll be able to get a higher paying job to help her family. She will graduate with more than $50,000 in federal student loan debt and a monthly payment of $336.

“Sometimes I feel really guilty,” she said of the decision to go back to school. “I feel a lot of pressure to make sure I find a high paying job just to justify making the decision.”

Getting a job, she said, “is not about looking forward to being able to buy things I want.”

“I need to get a job so I can earn enough to make my loan payments.”

Alicia Corby

Alicia Corby, 38, took out more than $225,000 in federal student loans to attend law school. Her current balance now is somewhere around $350,000.

“I owe about $40,000 a year in interest,” Corby, of California, said. The interest rates on her original loans were between 7 and 13 percent. She consolidated them, and now they hover between 6 and 8 percent. Still, “it’s almost impossible to pay the principal balance unless you’re making a ridiculous amount of money.”

Corby, a mom of three, left the workforce to take care of her kids. She put her loans in forbearance, but after running out of extensions, she had to return to work.

To her, “$10,000 would be like nothing,” but $50,000 in forgiveness would put her in a better position, even if it was still largely going to interest, she said.

If the government really wants to help alleviate the crisis, it needs to do something about interest rates and allow tax deductions for payments to the principal amount and the interest, she said.

“These are not private lenders. This is the federal government — and the interest rates are predatory,” she said.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com