In John Grisham’s legal thriller “Runaway Jury,” Nicholas Easter (portrayed by John Cusack in the movie version) connives his way onto a jury in a highly publicized trial. He gains the sympathy, respect and ultimately control of enough jurors to steer the verdict against the defendant. In both the book and the movie, Easter, his agenda driven by his tragic past, is the hero; the corporate defendants and the defense teams are the antagonists. The verdict is portrayed as just, and audiences leave satisfied, even overjoyed, with the result.

Even those who claim impartiality have backgrounds that point to potential unconscious biases or experiences that are likely to be incompatible with dispassion in a particular case.

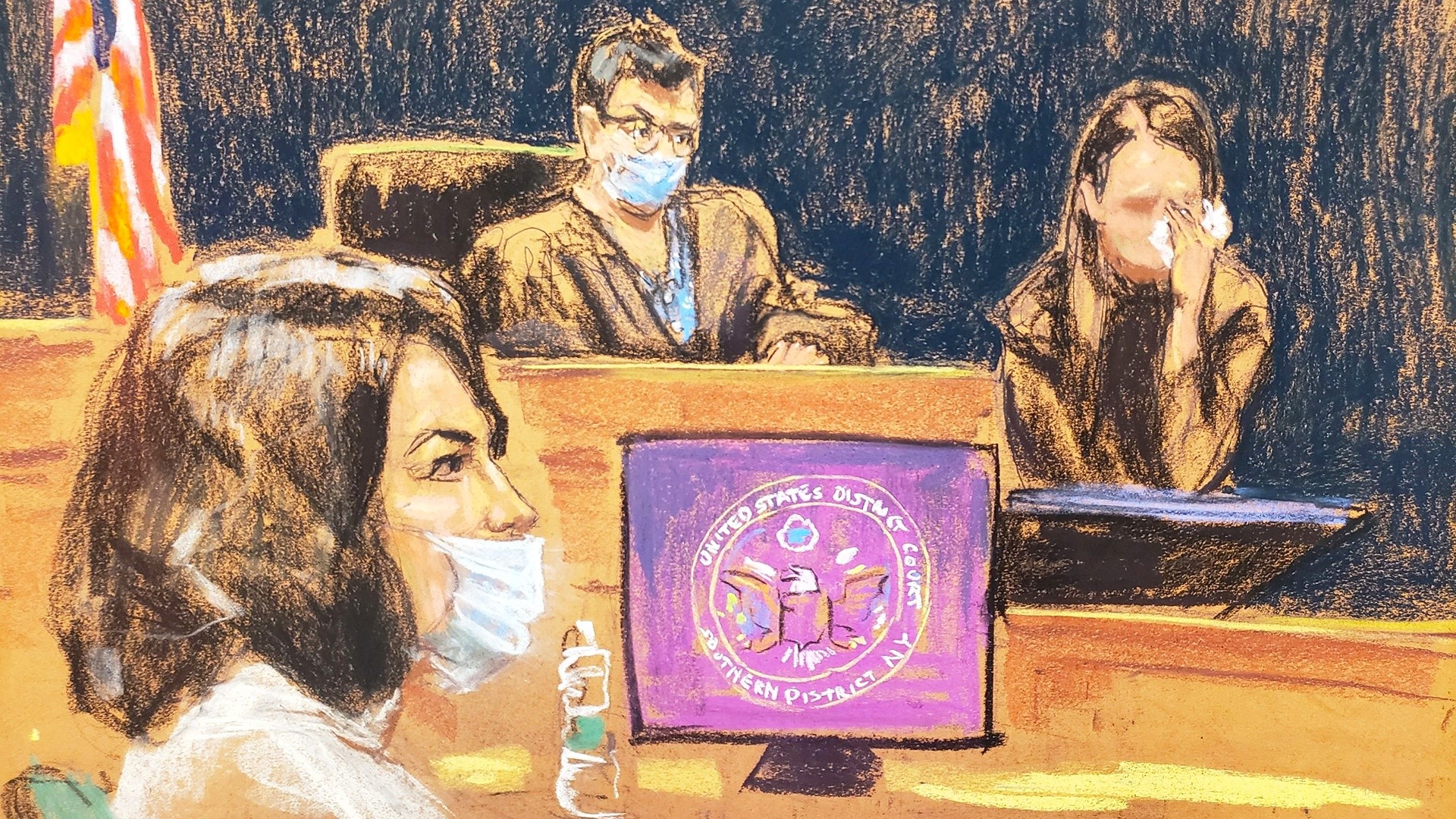

Grisham’s fictional narrative has startling parallels to the real-life trial of Ghislaine Maxwell. Maxwell was convicted by a federal jury in New York in late December of reprehensible sex-trafficking crimes and could spend her remaining life in federal prison. But after the trial, a juror made a stunning disclosure: He misled the court and the attorneys, under oath, about his own sexual abuse history as a child and drew on that history to influence other jurors, though it’s not yet clear whether he did so intentionally.

The verdict is now irrevocably tainted. The juror’s conduct has turned what should have been a victory for justice on its head. On Tuesday, the court will hold an unusual hearing — the presiding judge will question the juror to determine whether he lied to her and, if so, whether the lies reveal bias that should have disqualified him from serving. As former federal prosecutors, we have opposed dozens of motions for new trials for various purported irregularities. But this one is different. Whatever the court concludes about the juror’s credibility and bias, there is only one just outcome: There must be a new trial.

No competent criminal defense attorney would have agreed to seat a juror with a history of sexual abuse in a case that turned on the credibility of witnesses who would recount similar experiences. But it’s a history Maxwell’s attorneys didn’t know about — because, in jury selection, the juror “flew through” the court’s questions about the topic, he said.

Color us skeptical. The juror was sworn to tell the truth and was informed that he would be sitting for the Maxwell sex-trafficking trial as part of the high-profile case against Jeffrey Epstein. Maxwell had been charged, all jurors were told, with enticing underage girls to engage in criminal sexual activity. Prosecutors alleged that for several years, Maxwell and Epstein recruited and abused girls as young as 14.

In the court’s jury questionnaire, the juror was asked whether he’d ever been a victim of any crime, including whether he’d been a “victim of sexual harassment, sexual abuse, or sexual assault.” And he was asked to explain whether his past would affect his ability to serve fairly and impartially. He answered “no” to both of those questions, though he answered “yes” to inquiries elsewhere on the form. He also responded in narrative form to certain questions, noting, for instance, that he had learned about Maxwell’s connection to Epstein from CNN.

By his account, once he was on the panel he injected his abuse into the deliberations about ”predator” Maxwell, as he described her — sharing one story that apparentlysilenced the room — and helped return a guilty verdict on the most serious charges. Then, he turned to the media.He said he walked fellow jurors through his own experiences and purportedly helped them accept the recollections of the victims, who were testifying about abuse when they were minors.

At trial, these abuse victims had somegaps in their accounts — fertile ground for cross-examination and credibility challenges — but the juror said he argued in the deliberation room that the witnesses were still believable; he, too, claims to have told his fellow jurors that he could remember some details about his abuse but not others.

That’s a problem, regardless of whether the juror is another Nicholas Easter or whether he perjured himself on the juror questionnaire. Jurors should draw on their life experiences to assess evidence, though one could argue this juror’s advocacy crossed the line. No one could reasonably dispute, however, that he should have disclosed his past in jury selection.

There is a reason the defense and the prosecution get the chance to strike potential jurors in all criminal trials and that why the parties and the judge in the Maxwell case worked diligently to develop a jury questionnaire more than 20 pages long: Even those who claim impartiality have backgrounds that point to potential unconscious biases or experiences that are likely to be incompatible with dispassion in a particular case.

The Maxwell juror’s responses on the questionnaire and in subsequent interviews suggest that, like Grisham’s fictional character, he might have harbored a hidden agenda. But even if he didn’t, the appearance of a juror who is anything but disinterested, honest and faithful to his oath passing on the guilt of a person and rallying others to his side is so deeply antithetical to our criminal justice system that this verdict simply cannot stand. “Justice,” the famed jurist Felix Frankfurter once observed, “must satisfy the appearance of justice.”

In Maxwell’s case, prosecutors took the unusual and commendable step of alerting the court to the juror’s interviews and requesting an inquiry. In the vast majority of cases, the government vigorously opposes full-blown hearings, as it did recently in the trial against narco kingpin Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzmán. In that case, ajuror claimed the panel disregarded the judge’s instructions by “constantly” reviewing media coverage of the case. (The coverage summarized evidence that was ruled too inflammatory to be admissible at trial.)

And prosecutors usually succeed in their efforts not to have convictions vacated based on juror misconduct. The law is so firmly against revisiting jury selection and deliberations — El Chapo’s conviction wasaffirmed — that the Maxwell judge sought further briefing Tuesday before ordering a limited inquiry.

At Tuesday’s hearing, she will examine the juror herself, with input from the parties, focusing only on the responses the juror gave to two questions. Recent bindingprecedent allows a judge to deny a new trial even if a juror is found to have lied to the court in jury selection — and continues to do so at a hearing. The government, however, should go beyond its initial praiseworthy step and the minimum of what the law requires: It should agree to retry the case.

There’s no dispute about what the juror said to the media; he conducted a video interview. Even if he denies those statements or the court concludes after the hearing that the juror’s lies or misstatements in jury selection don’t sufficiently establish bias, would a reasonable observer feel satisfied with the process? Would you, if you were the defendant?

If we want to follow Frankfurter’s timeless admonition — deeply ingrained in our criminal justice system — then retrying Maxwell should be a no-brainer. Don’t let the image of a runaway juror trample our legal system.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com