When Monica Covington-Cradle, a speech language pathologist for more than 20 years, saw how the children she was tutoring had fallen behind on their reading skills during the pandemic, it was “mind-blowing,” she said.

“So many different kids in so many different types of schools, in every neighborhood” were struggling, said Covington-Cradle, who until recently worked with the tutoring service Brooklyn Letters in New York City. Many of the children, she said, faced difficulties with reading and phonics.

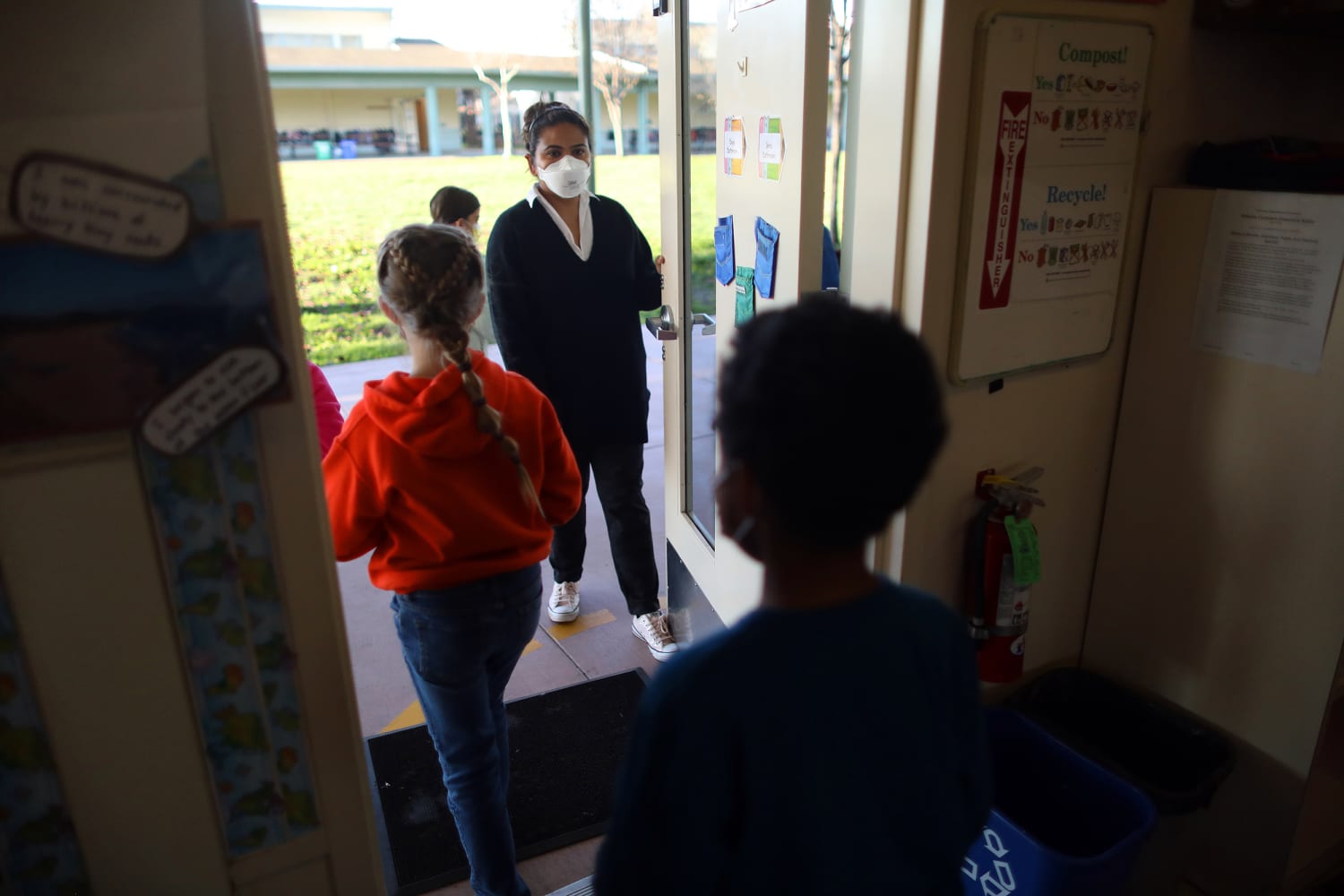

As schools across the nation face an acute shortage of teachers and other staff and as the remaining educators find themselves strained, demand for and interest in tutoring have increased with school districts and parents alike grappling with how best to serve the many students believed to have fallen behind academically because of the pandemic.

Demand for tutoring has skyrocketed at Brooklyn Letters, particularly in the last few weeks, said CEO Craig Selinger, who also is a speech language therapist.

“It’s probably been the highest volume of requests we’ve received since we started in 2010,” he said.

But as tutors go about assessing children, they’re finding that they’ve fallen behind in not only academic subjects — most notably literacy — but also skills like time management that are often picked up in school.

“Those are the building blocks for what comes later and if you don’t catch it early enough and intervene, it creates a pathway that gets harder and harder to correct as you get deeper into a student’s life,” said Megan Stubbendeck, CEO of the tutoring company ArborBridge.

One-on-one tutoring has often been financially inaccessible for many families, a tool not often tapped by communities most in need. But some states and school districts — encouraged, in part, by the U.S. Department of Education — are looking at ways to use the $122.7 billion allocated for education under the American Rescue Plan to make such individualized assistance more broadly available. Some are contracting private companies, while others are building their own programs.

Education Secretary Miguel Cardona, in a January speech outlining his priorities for the year, called on schools to use some of the billions they’ve received in Covid relief funding to invest in “targeted intensive tutoring.”

“I’d like to challenge all of our district leaders to set a goal of giving every child that fell behind during the pandemic at least 30 minutes per day, three times a week with a well-trained tutor who is providing that child with consistent intensive support,” he said. “We cannot expect classroom teachers to do it all.”

Resignations and retirements have mounted in schools across the nation due, at least in part, to the ongoing Covid pandemic. As of January, 44 percent of schools reported having at least one teaching vacancy, and nearly half had at least one staff vacancy, according to data released last week by the Education Department’s National Center for Education Statistics. More than half of those vacancies were because of resignations, the data found.

Meanwhile, several recent studies have found that more children, especially the younger ones, are behind than had been the case before the pandemic.

One study,by the curriculum and assessment company Amplify, found that “pandemic-related learning losses in early literacy are now disproportionately concentrated in the early elementary grades (K–2)” and that “persistent learning losses have widened the national gaps in early reading skills between Black and Hispanic students and their white counterparts.”

Those developments have brought more tutors to the front line.

In Arkansas, officials have created the Arkansas Tutoring Corps, which will recruit and train tutors and connect them with schools and other organizations.

Similarly, Tennessee is spending $200 million in federal funding to build the Tennessee Accelerating Literacy and Learning Corps, to provide tutoring to nearly 150,000 students over the next three years.

“The reality is that teachers, in general, way before the pandemic were not well-trained to teach literacy. That always existed and like many other things, the pandemic exacerbated an Achilles heel,” Selinger said. “Young children, they’re the ones that have been hit the hardest. When children are not being taught these critical skills in critical windows, it becomes a disaster.”

Teaching reading, in particular, can put a strain on already tapped out teachers because the specialized skills needed aren’t taught in many university education programs, Selinger, Covington-Cradle and others said.

“You’re now dealing with, how well can professionals in public and private schools manage that, Selinger said. “And before the pandemic, they were not equipped to manage that. They still aren’t, nothing has changed.”

Stubbendeck said tutors are encountering students who have fallen behind in the “executive functioning skills” typically learned in school environments. Those skills, such as time management, goal setting and breaking down problems into manageable pieces, are the kind “you need in your toolbox to be a good student and eventually a good person in a career.”

“It’s a fundamental thing that we all forget that we actually have to learn how to do that,” she said.

Steve Feldman, founder and managing partner of the Private Prep tutoring company, said that through no fault of teachers, social emotional learning and executive functioning skills were not as meaningfully addressed during the pandemic, with resources stretched thin and a focus on learning content during the major disruption of nationwide education.

But research has shown, Stubbendeck said, that educational gaps can be turned around especially if caught early.

“It’s something that we plan to be watching out for, those warning signs, not just this year or next year, but it’s probably going to be something that we’ll be looking at for the next five to 10 years,” she said.

Stubbendeck said intensive tutoring, as well as extended school days, summer programs and smaller class sizes, can help students improve learning loss.

Cardona also encouraged those strategies.

But for families that cannot afford such one-on-one interventions, more support of educators in schools is needed, Selinger said.

“Teachers are for the most part having a more difficult time because not only are these children more delayed, you have less resources, the shortages in schools, and almost all the teachers I know are dealing with burnout,” he said.

Feldman said tutoring services, when available, can offer a more “holistic approach to supporting our students” in need of extra assistance during the pandemic.

“We are sensitive to the demands on our students right now and to the mental health issues that so many students are facing,” he said. “And so we’re fortunate that we get to work with students one-on-one.”

Feldman said by building those relationships with students and communication with their parents, tutors are able to understand the individualized needs of the student “to be successful not just at getting the best grade possible or the best test score possible, but they’re also developing the skills they need to be successful as students.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com