This spring, the Grammy-winning and Oscar-nominated composer and jazz musician Terence Blanchard is bringing his opera, “Champion,” to the Metropolitan Opera in New York. The “opera in jazz,” as Blanchard describes it, is based on the extraordinary life of the late bisexual, Hall of Fame boxer Emile Griffith, who tragically beat Benny “Kid” Paret so badly in the ring in 1962 that Paret died days later. In “Champion,” which premiered in 2013, Blanchard recounts how an environment of hyper-masculinity and homophobia led to that fatal night at Madison Square Garden and how Griffith was haunted by it for the rest of his life.

“It just kind of clicked when I heard a quote that he said, which is in the opera: ‘I killed a man and the world forgave me, but I loved a man and the world wanted to kill me.’ That blew me away,” Blanchard told NBC News, paraphrasing a quote from Ron Ross’ 2008 biography “Nine … Ten … and Out!: The Two Worlds of Emile Griffith.”

“I started thinking about the first time I won a Grammy. I turned to my wife and gave her a hug, and wasn’t thinking about it. I’m just sharing the moment with somebody I care about. And he couldn’t do that,” Blanchard said, referring to his win in 2008 for the album “A Tale of God’s Will (A Requiem for Katrina),” his first of six. “He became welterweight champion, and he still had to hide in the shadows. Why? Because somebody else feels uncomfortable about it?”

The New Orleans native wrote “Champion” as a commission for the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, where it debuted in 2013 in partnership with James Robinson, who returns to direct the Met production; the libretto is by the Pulitzer- and Tony-winning playwright Michael Cristofer (“The Shadow Box”).

But Griffith’s story was on Blanchard’s mind long before everything clicked into place for his first opera. Beginning in the early 2000s, Blanchard started hearing about Griffith’s life from Michael Bentt, a former heavyweight champion who had met the storied boxer.

In both Blanchard and Bentt’s retellings of their conversations, the focus was on Griffith’s relative openness about his sexuality — including his struggle with it — despite being a Black Caribbean man who competed in a punishing sport at a time when people, much less athletes, hid their queerness from the world.

“We talked about Emile a lot, and that was the thing that always stuck with me in the story. He was a bisexual man from the islands, and most bisexual men in the islands never really talked about their sexuality. It’s something that they kept to themselves,” Blanchard said, noting that Griffith’s sexuality was common knowledge among his peers long before he came out publicly as bisexual in 2005 to a New York Times opinion columnist.

Bentt added, “For him to express that level of openness, for me, was quite profound.”

Griffith, who died at 75 in 2013, the year “Champion” premiered, was born on the island of St. Thomas, where he had a difficult childhood before moving by himself to New York as a teenager in the mid-1950s. In New York, he reconnected with his mother, who had been absent throughout his youth, and was hired in the millinery where she worked. That led to him being discovered by the factory owner, Howie Albert, who encouraged the teenage Griffith to go into boxing. Despite having much more interest in hat-making than boxing, as detailed in the 2005 documentary “Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story,” Griffith agreed to pursue fighting with Albert, whom he saw as a father figure, acting as his manager.

Under the tutelage of trainer Gil Clancy, Griffith soon proved to be a worthwhile investment for his handlers — and a major source of income for his family — going largely unchallenged in amateur fights, winning a Golden Gloves championship, and eventually proving to be a contender for the welterweight title. That landed him in the ring in 1961 with the defending welterweight champion, Paret, who lost his title when Griffith knocked him out in the 13th round. Paret won the title back in a split decision later that year.

As the boxers’ rivalry deepened, so, too, did their mutual animosity, which boiled over at the weigh-in for their second fight, when Paret referred to the closeted Griffith as a “maricón,” a Spanish slur akin to faggot. The Cuban Paret then repeated the taunt at the pair’s weigh-in before their final contest on March 24, 1962, at Madison Square Garden. The televised fight ended in the 12th round with Paret pinned in the corner, receiving a steady stream of blows to the head, until Griffith was eventually pulled away from his opponent’s unconscious body. After 10 days in a coma, Paret died from fight-related injuries.

“He shouldn’t have been in the ring. He had just had a fight two months prior with a very hard-hitting guy, Jean Fullmer, who, like, beat him to death, so he was probably still injured when he got in the ring with Emile,” Blanchard said of Paret. “It wasn’t Emile’s fault. He was doing what he was trained to do; he was competing. And in the process, because of the lack of regulations, a man lost his life. And he carried that burden around for years.”

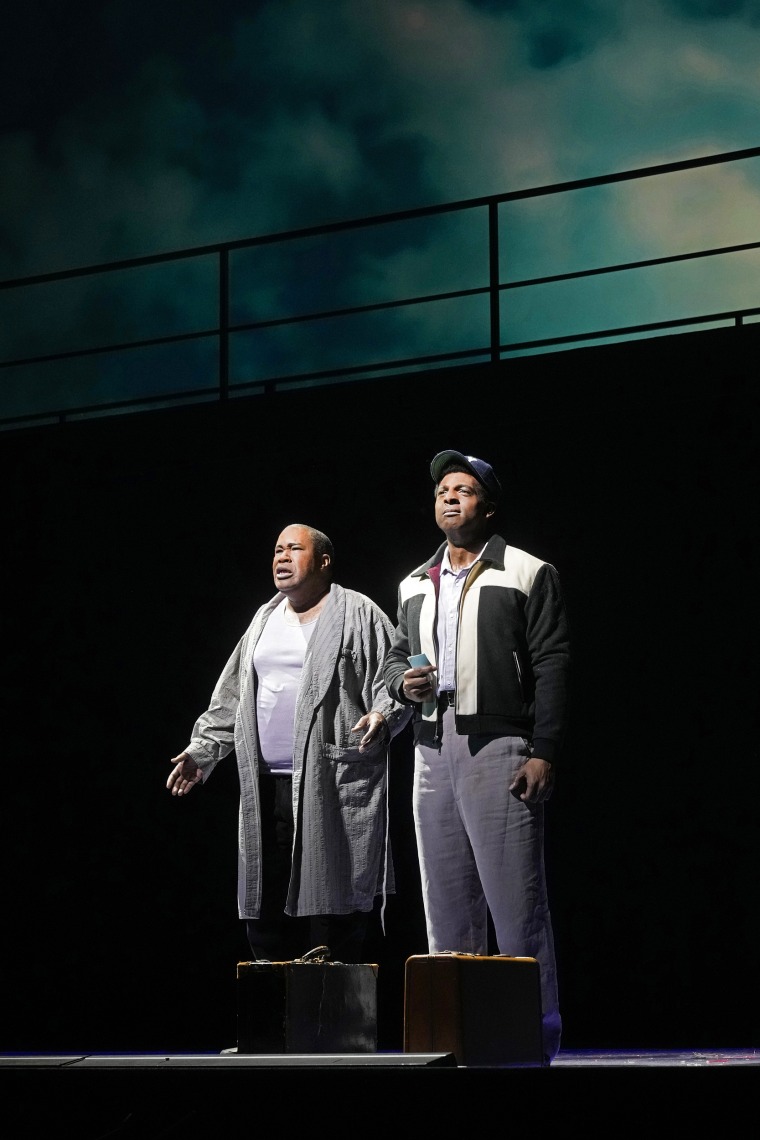

In “Champion,” those fateful events of the 1960s, which would come to define Griffith’s life, are portrayed in flashbacks featuring bass-baritone Ryan Speedo Green as an imposing, young Emile Griffith and baritone Eric Greene as Benny Paret. Bass-baritone Eric Owens plays the present-day Griffith living in relative obscurity, haunted by the ghost of Paret.

In two acts, the opera charts Griffith’s rise to the heights of welterweight boxing and his eventual descent into a life colored by guilt and illness, whose defining moments were the death of Paret in his youth and a meeting with Benny Paret Jr. in his final years.

While Act II focuses on Griffith’s twilight years and his struggles with dementia and injuries from a brutal attack outside of a gay bar in the 1990s, the opening act focuses on the boxer’s early life and his rivalry with Paret. And it culminates in a dramatic retelling of the 1962 fight, preceded by the opera’s centerpiece, an aria titled “What Makes a Man a Man,” which is sung by Green. In the climactic scene, which features a staggering number of singers, dancers and actors, Griffith and Paret go head to head in a ring that spins around to show the choreographed fight from every angle. And, as archival footage appears on the massive screens that dominate designer Allen Moyer’s set, Griffith delivers more than 17 blows in less than seven seconds, sealing Paret’s fate.

“Benny and Emile had a very personal history, so I tried to get [the singers] to deep dive into their own personal history — as Black men, as outcasts — and tap into that,” Bentt, who was brought on as a fight coordinator for the Metropolitan Opera staging, said of preparing Green and Greene for the climactic moment. “You’re not tapping into that as a way of camaraderie; you’re tapping into that as a way of ultimately trying to destroy each other.”

“Society is fascinated by boxing, but I don’t think that the public really understands where the boxers’ drive to succeed comes from,” Bentt added “For the vast majority of boxers, that drive to succeed comes from deprivation — abusive mothers, abusive fathers, abusive societies. If a boxer gets in the fold of the right manager and trainer, and he has a chance to express that, he’s lucky.”

Painful personal histories aren’t unexplored territory for Blanchard. His wildly popular second opera, “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,” which won the composer his most recent Grammy and also starred Green, is based on Charles Blow’s memoir of the same name, which describes how the journalist and commentator was sexually abused during his childhood and went on to struggle with his sexuality as an adult.

The success of “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,” which became the first work from a Black composer to be staged at the Metropolitan Opera in 2021, led the opera house to commission a new opera from Blanchard and to propose staging “Champion,” which the composer adapted for Green’s voice, the cavernous venue and its large company.

Using what he’s learned over a decade-long pivot into composing operas, after making a name for himself with studio albums and 30 years’ worth of film scores for Spike Lee, Blanchard added sections for the production’s more-than-40-person chorus and two new arias, which are played by a full orchestra and jazz ensemble conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin, the Metropolitan Opera’s first openly gay music director. Together with the opera’s original compositions, the additions and revisions blend a variety of musical styles — from swing to samba, brass band and blues — through which the composer crafts a thoroughly modern, operatic world all his own.

“Like anything else in the composition world, you utilize everything that’s at your disposal,” Blanchard said, describing how different styles of music can combine, even in one scene, to evoke multiple moods. “A lot of it is trying to find the appropriate moments for it.”

Blanchard — who has built ongoing, yearslong collaborative relationships with Robinson, Moyer, Nézet-Séguin, choreographer Camille A. Brown and many of the opera’s other key creative voices — joked that the trade-off of using everything that’s at your disposal is that it creates havoc during rehearsals. But when it comes together, he said, the feeling is addicting.

“When we’re on stage [during rehearsals], there’s just so much you get involved in. There’s so much going on — with the lighting, the imagery, set design and the wardrobes. It’s hard to keep track of it all. It’s almost like a photograph being out of focus,” Blanchard said. “But as the rehearsals go on, it starts to become more focused, and then when you get to that final one, and it’s like a sharp image, that’s when it all clicks. Prior to that, it’s a collection of different things — lighting, imagery, and all of that stuff — but when it clicks, it’s an opera; it’s one thing. That’s the drug for all of us.”

“Champion” will run at The Metropolitan Opera in New York City from April 10 to May 13. It will also show live in movie theaters around the world on Saturday, April 29, at 1 p.m. ET as part of the “The Met: Live in HD” series.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com