When Resmaa Menakem heard a Minnesota judge sentence Derek Chauvin to 22 and a half years in prison for the murder of George Floyd, he was angry.

“My first thought was, ‘Here we go again, this is the same old bull—- couched as objectivism, couched as law,'” said Menakem, an author and a clinical social worker who specializes in racialized trauma.

Although the sentence is one of the longest prison terms ever imposed on a U.S. police officer in the killing of a Black person, it fell short of the 30 years prosecutors had requested.

Menakem took particular exception to Hennepin County Judge Peter Cahill’s finding that evidence at the trial did not indicate that four children who witnessed Floyd’s death were traumatized, as prosecutors asserted.

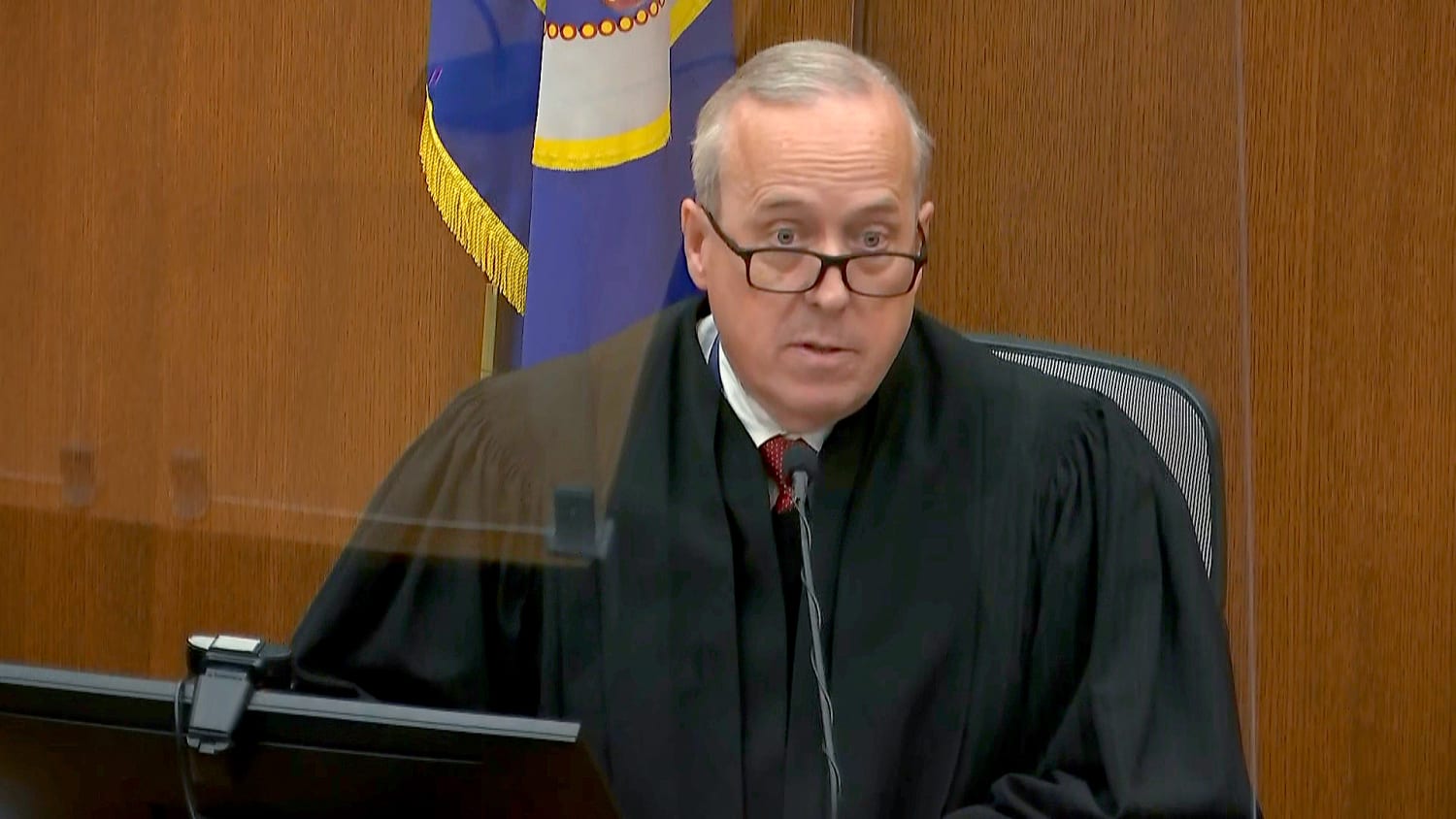

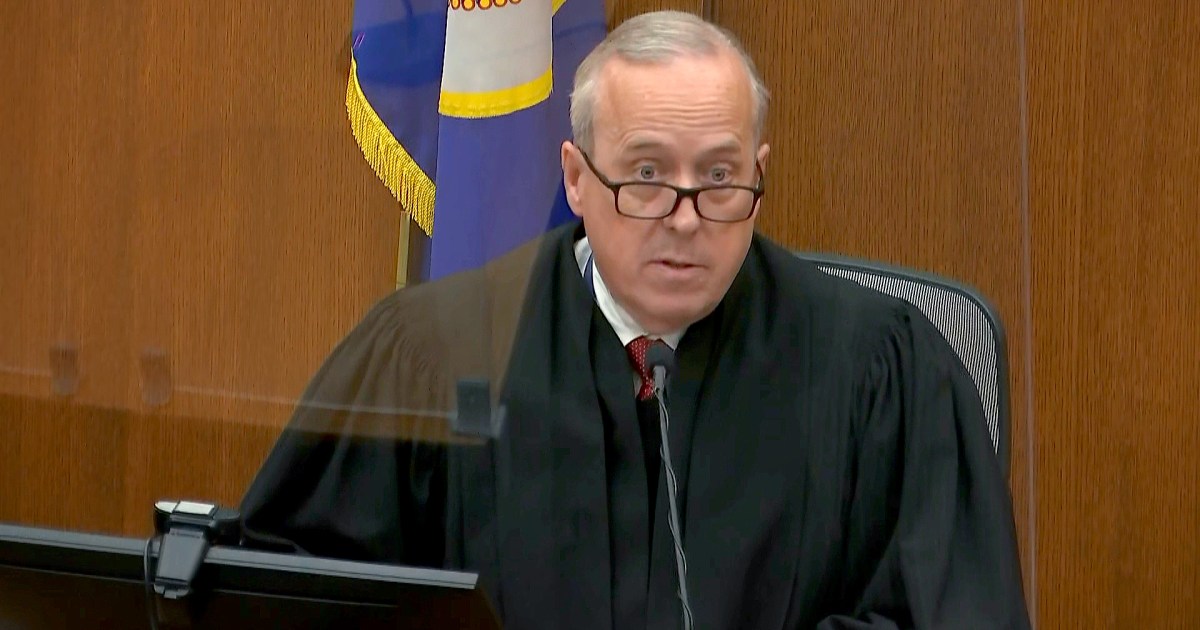

When Cahill announced a week ago that he would go above the 12½ year presumptive sentence, the judge noted that his decision was driven by two aggravating factors: the former officer’s abuse of his position of trust and authority, and the “particular cruelty” with which he treated Floyd.

In a sentencing memo, Cahill said the presence of children on the scene did not factor into his decision because the affect on them was not “so substantial and compelling” as to warrant it.

Some legal and childhood trauma experts question that call and whether the judge was equipped to make such a determination.

Mary Moriarty, a former chief public defender in Hennepin County, said the conclusions Cahill drew in the sentencing memo demonstrate a “fundamental misunderstanding of trauma.”

“Human beings react in incongruous ways when faced with trauma,” she said.

The presence of children on the scene when Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck until he stopped breathing was one of four aggravating factors prosecutors had hoped would cause Cahill to sentence Chauvin to three decades in prison.

But the judge found that the children’s presence alone was not enough to warrant a departure from the sentencing guidelines. As part of his explanation, Cahill wrote that the children were not victims “in the sense of being physically injured or threatened with injury” and that they “were free to leave the scene whenever they wished.”

Cahill also wrote that he observed three children, including Darnella Frazier, who was 17 when she recorded the widely seen video of Floyd and uploaded it to Facebook, and her 9-year-old cousin, “smiling and occasionally even laughing” in a video from the body camera of one of the officers at the scene on May 25, 2020.

“Although the state contends that all four of these young women were traumatized by witnessing this incident, the evidence at trial did not present an objective indicia of trauma,” Cahill wrote.

David Schultz, a political science professor at Hamline University and a visiting law professor at the University of Minnesota, said that Cahill, on his own, probably can’t reach a conclusion about whether the children were traumatized.

Basing a decision on an observation of children recorded laughing or smiling during a potentially traumatic event may have been a misstep, he said, because people react to stress in a variety of ways, including nervous laughter.

Lawyers are trained in the law, Schultz said.

“We’re not trained in human psychology,” he said. “We’re not trained in medicine.”

He added: “That to me is my underlying criticism: He reached a conclusion, one way or the other, in an area where he is not an expert, and he should have consulted some experts in the area.”

Cahill declined a request for an interview. A spokesman for the Hennepin County District Court said that “judges cannot comment on their decisions outside of the official court record.”

“As such, Judge Cahill will not be providing any additional comments about his sentencing memo in the Chauvin case,” the spokesman said in a statement.

While Cahill’s sentencing memo refers to bodycam video of the children on the scene as part of his consideration, it leaves out the trial testimony of those same witnesses.

For instance, Alyssa Funari, who was 17 at the time, testified that she felt compelled to stay at the scene outside Cup Foods, where she was going to buy a cord for her cellphone. She recorded several minutes of the deadly encounter and testified, at times through tears, that she felt helpless watching Floyd being held face down on the pavement.

“I knew that it was wrong, and I couldn’t just walk away, even though I couldn’t do anything about it,” she said in court.

Frazier, now 18, testified through tears that Floyd’s death has haunted her, causing her to lose sleep.

“It’s been nights I stayed up apologizing and apologizing to George Floyd for not doing more and not physically interacting and not saving his life,” she said in court. “But it’s like, it’s not what I should have done, it’s what he should have done,” she added, in an apparent reference to Chauvin.

Menakem, Moriarty and Schultz expressed disbelief in separate interviews that her testimony did not factor into the sentencing.

“It didn’t move him enough to where he thought it should be a factor in his judgment,” Menakem said.

A person who helplessly witnesses another person be brutalized as Floyd was can be “vicariously traumatized,” Menakem said.

“You want to give aid, you want to mobilize yourself to do something, but yet the physical threat and the emotional threat, all of this stuff stops you from rendering aid,” he said. “That’s secondary trauma.”

It is possible that the longer the bystanders stayed at the scene, the more they were traumatized, Schultz said. He wonders how the judge arrived at his conclusion.

“If it was simply based upon even just the testimony and on the video, that’s probably still not enough to reach that conclusion,” he said.

Schultz said it is possible that trauma experts were consulted as part of the pre-sentencing investigation.

A pre-sentencing investigation report, which is usually nonpublic, is typically prepared by a probation officer who will interview the prosecutor, members of law enforcement, victims, mental health and substance abuse treatment providers and the defendant’s family members, associates and employer. The report includes such personal information about a defendant as family history, as well as physical, mental and emotional health.

Nothing would have precluded agents from the Department of Corrections from interviewing Frazier or from consulting with a psychologist or a psychiatrist if they were unsure as to what impact, if any, Chauvin’s actions had on the children who witnessed Floyd’s death. It’s not clear if that happened in this case.

Menakem, who wrote “My Grandmother’s Hands,” a 2017 book that examines the damage caused by racism in America, believes that unconscious racial bias could have played a part in Cahill’s decision-making.

As examples, he pointed to studies that show physicians and other health care professionals don’t always recognize Black patients’ pain — in some cases because they believe they have a higher threshold for it — and that Black children are more likely to be viewed as adults.

“Black pain, Black horror, Black discomfort has never been a central issue in America,” Menakem said. “Black pain has always been something that is cursory.”

Menakem said that he believes Cahill, who was a judge for a number of years in juvenile court, is experienced in childhood trauma.

“To assume he just doesn’t understand trauma would be an error,” Menakem said. “He understands it.”

Instead, Menaken said, Cahill “just decided that it didn’t have any merit.”

What’s more, Moriarty said prosectors didn’t need to prove the children were traumatized to begin with, only that they were present.

The prosecution, she said, did both.

“I thought their testimony, particularly that of Darnella Frazier, certainly proved that they were traumatized,” she said, adding, “I think he came to that conclusion based on his personal beliefs and understanding of trauma.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com