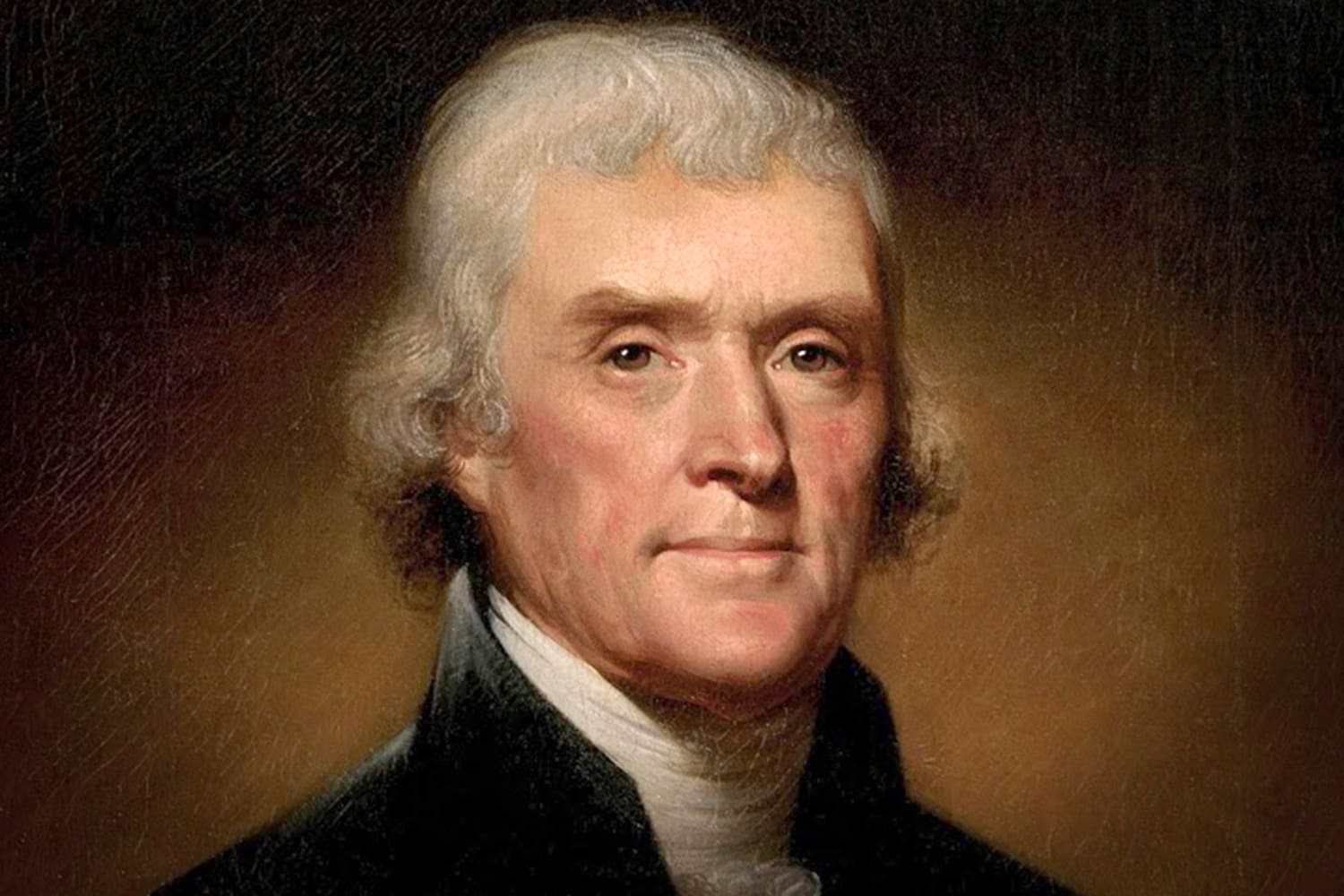

American political leaders are compelled by the Constitution to provide for the “general welfare” of the people. Following this logic, vaccination has traditionally been viewed as a godsend. When Thomas Jefferson first learned of the promise of vaccination, just before taking office as the third president of the United States, he wrote that “every friend of humanity must look with pleasure on this discovery, by which one evil … is withdrawn from the condition of man.”

While the political currents can be fickle, encouraging vaccination has long been a bipartisan goal.

But vaccines have never undergone a more-sustained partisan assault from political leaders than what we’re now witnessing. To the contrary, the Founders, who disagreed on many issues, supported vaccinations enthusiastically, especially Jefferson. And while the political currents can be fickle, encouraging vaccination has long been a bipartisan goal.

In contrast today, as the delta variant surges among the unvaccinated, Republican legislatures and governors are restricting vaccination efforts and, most alarmingly, even the promotion of vaccines to the public. Perhaps the most jarring example is in Tennessee, where the state’s top vaccination official was harassed and fired last week after she said Republican state legislators had objected to her efforts to encourage teenagers to get vaccinated.

Some of the earliest laws in Colonial America were restrictions intended to keep the public safe from epidemic diseases, which was viewed as one of the foremost duties of government. Outbreaks of disease in the 18th century required an immediate response from officials who enacted restrictive quarantines, isolated and provided care for the infected, and, in extreme cases, oversaw the shutdown of entire communities to control the spread of disease.

These early epidemic orders were not without critics. Merchants often complained about how quarantines and shutdowns hampered their businesses. Enslavers worried about the damage an outbreak might do to the people enslaved on their plantations. The solution? Vaccines. When vaccination for smallpox was introduced to the United States, after the English doctor Edward Jenner published his experiments with cowpox in 1798, it offered a cheap way to prevent epidemics without harming businesses.

No matter how bitter the political climate, vaccines remained bipartisan. Despite a harshly contested partisan election in 1800 that eventually saw Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans defeat Federalist incumbent John Adams, both Adams and Jefferson cheered the discovery of vaccination.

So enthusiastic was Jefferson that he devised a method for transporting vaccine matter over long distances — a feat that was notoriously difficult before refrigeration. After having several of his slaves vaccinated, Jefferson called for the vaccination of some 200 people, performing dozens of vaccinations himself on his white family members and enslaved persons at Monticello.

So enthusiastic was Jefferson that he devised a method for transporting vaccine matter over long distances.

Jefferson marveled that vaccinated people missed so little work, commenting to a Delaware physician in 1801 that “a smiter at the anvil continued in his place without a moment’s intermission.” Jefferson naïvely hoped that the “liberal diffusion” of the evidence supporting vaccination would lead to its broad adoption without much government intervention, but vaccinations in the United States began to lag behind more coordinated efforts in other nations.

To correct this, newspapers supporting both political parties supported Massachusetts’ 1810 law known as “The Cow Pox Act,” which stated that it was “the duty of every Town, District, or Plantation” to establish a board of health “to superintend the inoculation of the inhabitants,” therein. Other states were slower to take such measures, especially when smallpox was not present.

Calls for a national vaccination program coalesced under President James Madison. Congress eventually passed and Madison signed “An Act to Encourage Vaccination,” popularly known as the Vaccine Act in 1813.

While some wanted the act to compel communities to require vaccinations like in Massachusetts, the Vaccine Act was more modest. Its goal was to ensure that anyone who wanted the smallpox vaccine could receive it from a reliable source for a low cost. The program was underfunded and ultimately canceled nine years later. And by the 1820s, some in Congress began calling the program an unconstitutional intrusion on states’ rights to provide for the health of their own citizens.

The demise of the national vaccine agency left immunization efforts to the states. And while their leaders did not undermine the concept of vaccination itself, or the health officials within their states who promoted it, efforts to combat epidemics in the later 19th-century were often haphazard affairs that failed to protect the truly vulnerable like newly freed Black Americans or recent immigrants. In the early 20th century more state and local governments mandated the vaccination of school children, business owners often required their workers to be vaccinated, and the United States did not see another outbreak of smallpox after the 1940s. These sometimes aggressive actions did trigger a vocal but largely disorganized anti-vaccination movement, which contested state health laws in court, but it was not central to any major political party.

Even as providing health care to all Americans became a partisan ideal in the 20th century, vaccination programs have long stood as obvious, apolitical duties of government. While such programs have not always been popular with everyone in the history of the United States, the nonpartisan promotion of vaccination is nearly as old as the country itself. That the ongoing Covid-19 epidemic is breaking this long American tradition is another troubling sign for the future of the United States and its people.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com