But importantly, Tamagotchi was also one of the very first video games to be marketed primarily to girls. When consoles like the Nintendo were first released, according to Crowley, they were placed on the shelves exclusively in the boy’s section of Toys “R” Us. With the Tamagotchi, the opposite happened. It challenged the hyper-masculinity that was associated with video games back then, he says.

“The Tamagotchi provided access to people who had been ignored over the last decade in the video game industry,” Crowley says.

Ironically, it did so by playing into the gender stereotypes that were dominant at the time, and to an extent still are. It was a toy that appealed to girls through what were seen as stereotypical female traits—like the mother instinct or the concept of nurturing. For girls to be allowed to play video games, they would have to assume the role of a caretaker.

“The Tamagotchi very much reflects the social conditions of its moment of emergence,” says Crowley. “So on the one hand, we’re finally offering it to girls, while on the other hand, it was saying like ‘this is what girls do, this is what’s appropriate.’”

The Past and Future of Virtual Reality

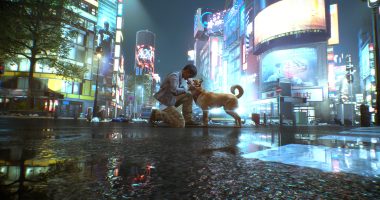

If not the first, the Tamagotchi was an early example of a video game that blurred the lines between the digital world and the real world, or virtual reality.

In 1997, the Finnish addiction specialist and sociologist Teuvo Peltoniemi issued a gloomy warning about the Tamagotchi in the South China Morning Post: “Virtual reality is a new drug, and Tamagotchis are the first wave. It’s not just some fad that will go away. [Tamagotchis] are an ideal example of the possible threat of a virtual world becoming, in the future, a real dependence problem needing treatment.”

As an addiction specialist, Peltoniemi became increasingly worried when he saw kids glued to their Tamagotchis in schools and at the dinner table. In his work, he used the Tamagotchi to show how children and adults could develop over-the-top emotional responses to virtual characters.

“The Tamagotchi, I think, was the first little tool that was accessible to the average consumer where you could find virtual reality, and its most important feature was that it appealed to people’s feelings and sentimentality through care,” Peltoniemi tells WIRED.

“People developed really strong emotional attachments to their Tamagotchis because they, in a way, had a relation with the digital pet, to the extent that people felt they had enough human features to hold funerals when they died,” he continues.

For some, the Tamagotchi has kept its appeal even into adulthood. Kim Matthews, 32, from Australia is one of those people. In childhood, her “tama” was one of her favorite toys. In adulthood, it still is—though now more for nostalgic purposes. She was given her first Tamagotchi for her eighth birthday and immediately fell in love—competing with her friends to see who could keep theirs alive the longest.

“Tragically, my first Tamagotchi unknowingly went for a swim with me in the pool one day,” says Matthews. “I was devastated.”

With a collection of 71 Tamagotchis amassed over her lifetime, Matthews still struggles to explain what makes her care for them so much, even after 25 years.

“I just think they’re neat,” she jokes, a reference to a Marge Simpson meme. “Maybe it’s a ’90s kids’ thing.”

More Great WIRED Stories