WASHINGTON — Is the Senate engraving an invitation to future presidents to trample on Congress?

The second impeachment trial of President Donald Trump will soon come to a close, and, no matter what the Senate does, it won’t compare in force — literal or metaphorical — to the whirlwind the former president unleashed on Congress on Jan. 6.

But it is both expected and remarkable that the Senate will do nothing to punish Trump or protect its own power. Republican senators are on the verge of simply wiping away Trump’s trespasses, as if they never happened.

Congress and the courts have given the president wide latitude to expand executive power for years, and some lawmakers say they should at least be able to draw a line at physical violence.

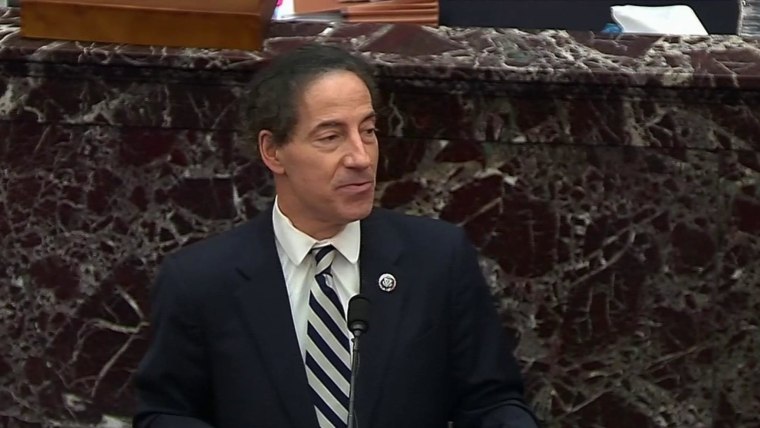

“Exactly what he did is the new standard for what’s allowable for him or any other president who gets into office,” Rep. Jamie Raskin, D-Md., the lead House manager, said Friday. “We’ve got the opportunity now to declare that presidential incitement to violent insurrection against the Capitol and Congress is completely forbidden to the president of the United States under the impeachment clauses.”

Don’t hold your breath. Trump has acted with impunity since he took office.

He bullied and threatened lawmakers for four years. He defied their oversight powers. He unilaterally withheld and redirected funds. On a mostly party-line vote, the Senate said last year that he should not be removed from office for using federal money to pursue a foreign investigation of his political rival.

Voters, many Republicans said at the time, should decide Trump’s fate.

When the voters cast Trump aside, he rallied a mob in Washington and sent them to the Capitol to stop the certification of his defeat. He egged on the rioters as police were overrun, his vice president was evacuated, and House and Senate members cowered in fear. He scoffed at House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s pleas for help.

You got what you deserved, Trump implicitly told Congress that day in his tweets and phone calls to members. He refused to appear as a witness in his own defense against impeachment. His lawyers mounted a case that amounted to suggesting an alternate reality to lawmakers who had personally endured the attack. The Trump team told senators that Congress is powerless to hold the former president accountable because he was impeached both too quickly and too slowly. Despite its relative brevity, the defense presentation found ways to undermine the logic, law and the legislative branch of government.

Trump knows the Senate doesn’t have the power to respond to him in kind.

Congress may raise armies, but none of its members have Trump’s ability to rouse his base. They can’t send rioters to his doorstep. They aren’t equipped to sanction him like they do foreign dictators, or expel him from the country or even put him in prison.

Their power is limited to convicting Trump of high crimes and misdemeanors against the republic, prohibiting the 74-year-old from holding future office, or perhaps issuing a sternly worded — and meaningless to Trump — censure of some sort.

And even those rebukes may be out of reach for a Senate that seems intent on proving that it is unwilling to take on a powerful president. House Democratic impeachment managers have warned that the Senate will encourage future assaults by a president on the legislative branch if it fails to take any action against Trump.

Trump wasn’t even at the apex of his power when his supporters crashed into the Capitol. He was in the weakest stretch of his presidency, the lame-duck period between his successor’s election and inauguration.

What would a future president like Trump — Republican or Democrat — do to Congress at the start of a term or in the midst of one? The Senate, evenly divided between the parties, may be incapable of convicting Trump. Doing so would require one-third of the Republican senators to subordinate partisan concerns or personal loyalty to Trump.

Beyond the message sent to future presidents, inaction by the Senate may also send a message to future rioters, though that’s not something lawmakers really want to talk about. They don’t want to put a fine point on their own vulnerability. They don’t want to exclaim the obvious conclusion that any citizen could draw: the leader of an insurrection won’t be held responsible. In other words, you can risk life, limb and imprisonment safe in the knowledge that he won’t suffer for your actions.

Over time, Congress has ceded much of its institutional power to the presidency, including all or some of its authority over war, treaties and budgets. There is room for spirited debate about which branch of government should have the most influence in those areas and others.

Until last month, there was no debate about whether the president had the right to launch an assault on the Capitol. Now, the Senate is on course to step aside whenever it happens.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com