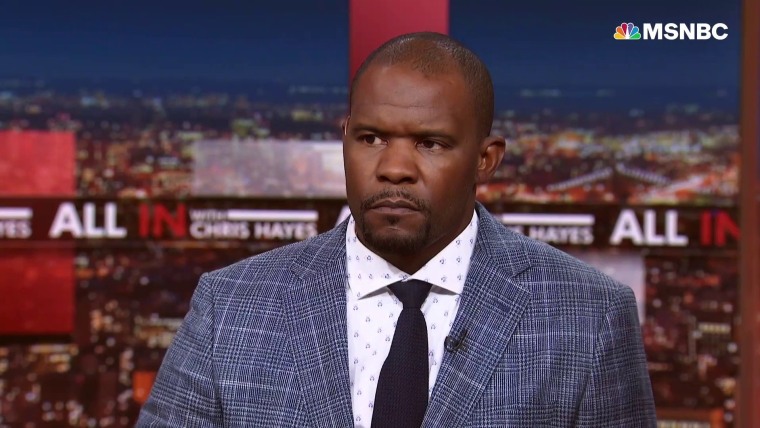

Former Miami Dolphins head coach Brian Flores said he didn’t need to file a federal lawsuit against the NFL alleging racist hiring practices “to see that there’s a problem” with the so-called Rooney Rule.

“I think the numbers speak for themselves,” he told NBC News on Wednesday as his complaint rocketed across the sports world and reignited discussions about the league’s lack of diversity among its coaching staff and the upper rungs of management.

The Rooney Rule, named after Dan Rooney, the former Pittsburgh Steelers owner and chairman of the NFL’s diversity committee, was adopted in 2003 and requires teams to interview diverse candidates for coaching jobs. In addition, at least “one minority and/or female candidate” must be interviewed for senior-level positions.

But that almost two decades later there is just a single head coach who is Black — Mike Tomlin of the Steelers — among the NFL’s 32 teams is one of many glaring examples of how the Rooney Rule, which had been making strides to showcase diversity hiring, has returned the league to a pitiful place, sports industry and legal experts say.

When the Rooney Rule was first implemented, “we had a great run,” Cyrus Mehri, a civil rights lawyer who helped author its language, said. “Not only was it leveling the playing field just by getting people who may otherwise be overlooked in the door, but they were getting hired.”

“How is it that we’ve plummeted to almost being back to square one?” he asked.

Before the rule went into effect, coaches of color were hired about 2 percent of the time, said Mehri, who co-founded the Fritz Pollard Alliance, an NFL watchdog group that supports equity and inclusion in professional football.

After the rule, he said, the rate of coaches of color hired rose to 20 percent.

There were celebrated examples: During the Super Bowl in 2007, when the Indianapolis Colts played the Chicago Bears, both head coaches were Black, the first time in a championship game. Tony Dungy of the Colts became the first Black head coach to win a Super Bowl, beating out Lovie Smith of the Bears.

On the executive side, Jerry Reese, who is Black, was general manager of the New York Giants when the team won the Super Bowl in 2008 and 2012.

But in 2018, the hiring of Jon Gruden, who is white, as head coach of the then-Oakland Raiders drew scrutiny when it was revealed that Raiders owner Mark Davis admitted that the team had already agreed to a deal to hire Gruden even before interviews with any candidates of color were conducted.

The NFL cleared the team of violating the Rooney Rule because it did end up interviewing two diverse candidates, although neither were ultimately chosen.

Gruden resigned as head coach last year after emails containing racist, homophobic and misogynistic language were uncovered from a time before he was hired.

Still, the appearance that the Raiders could evade any type of enforcement was a signal to other teams, Mehri said.

“The NFL declined to put the hammer on the Raiders,” he said. “It’s a loud and clear message that it doesn’t matter. We don’t care anymore. The time is gone.”

But Flores’ lawsuit and the roadblocks he said he experienced in trying to land a job as a head coach after leaving the Dolphins last month has turned up the heat on the issue yet again.

Throughout his lawsuit, Flores, the son of Honduran immigrants from Brooklyn, New York, stressed that of the NFL’s entire player roster, 70 percent are Black, according to The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport, a part of the University of Central Florida College of Business Administration.

Meanwhile, his lawsuit said, only one of the league’s 32 teams employs a Black head coach; three employ a Black quarterback coach; four employ a Black offensive coordinator; eight employ a Black special teams coordinator and 11 employ a Black defensive coordinator. As for the top position of general manager, only six teams have a Black person in that role.

“This is not by chance,” the complaint said, and the numbers “are the result of race discrimination.”

The NFL has denied Flores’ allegations and said in a statement it would fight the suit.

“The NFL and our clubs are deeply committed to ensuring equitable employment practices and continue to make progress in providing equitable opportunities throughout our organizations,” the league said.

Since the Rooney Rule was instituted, 27 of 127 head coaching jobs, or about 21 percent, have gone to minorities. Last year, of the seven openings for a head coach, just one went to a Black candidate: David Culley, who ended up getting fired from the Texans after one mostly losing season.

Besides Tomlin, other current nonwhite head coaches include the Washington Commanders’ Ron Rivera, who is Latino, and the New York Jets’ Robert Saleh, who is of Lebanese heritage.

In 2021, the league saw 13 Black coordinators and three Black general managers hired.

But this year, of the nine vacant head coaching positions, white candidates have been hired for four openings so far.

“Except for the head coaching positions, overall there was significant and historic progress for minority hiring in 2021,” Troy Vincent, the NFL’s executive vice president of football operations and a former player, told The Associated Press in December. “Statistically, 47 percent of interview requests for coaches, coordinators and GMs were for minority candidates, and 35 percent of open hires went to minorities, nearly doubling 2020 in both interviews and hires.”

While it appears to be an improvement, the league is playing catch-up, N. Jeremi Duru, a professor of sports law at American University who writes about race and the NFL, said.

Progress can be achieved not by doing away with the Rooney Rule, but by strengthening it further, he added.

It’s happened before.

In the wake of Gruden’s hiring in 2018, the NFL toughened up the rule, mandating that a team with an open head coaching job has to interview at least one outside diverse candidate or someone from a list approved by the NFL’s advisory board. Teams also have to keep records of the interview process and make them available.

But Duru said teams that fail to play by the rules should also be penalized. The league, independent of Flores’ lawsuit, can also create programs with goals to diversify team ownership and the corps of top-ranking officials.

“Whatever the outcome of this lawsuit, it has to do more,” Duru added. “The status quo is unacceptable.”

Melissa S. Woods, who specializes in labor and employment law as a partner at the firm Cohen, Weiss and Simon LLP, said the responsibility cannot be placed solely on Black players to ensure they are good enough to eventually apply for a coaching position and get hired.

The NFL, too, must be thoughtful about mentoring those players, Woods said, as well as reporting its progress and ensuring whether leaders are truly committed to hiring diverse candidates.

Giving financial incentives to teams that are doing the work, she said, such as affording them a higher draft pick or a larger bonus, could also be options.

The Rooney Rule “can absolutely work when it’s done right and taken very seriously,” Woods said. “But we’re not there yet.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com