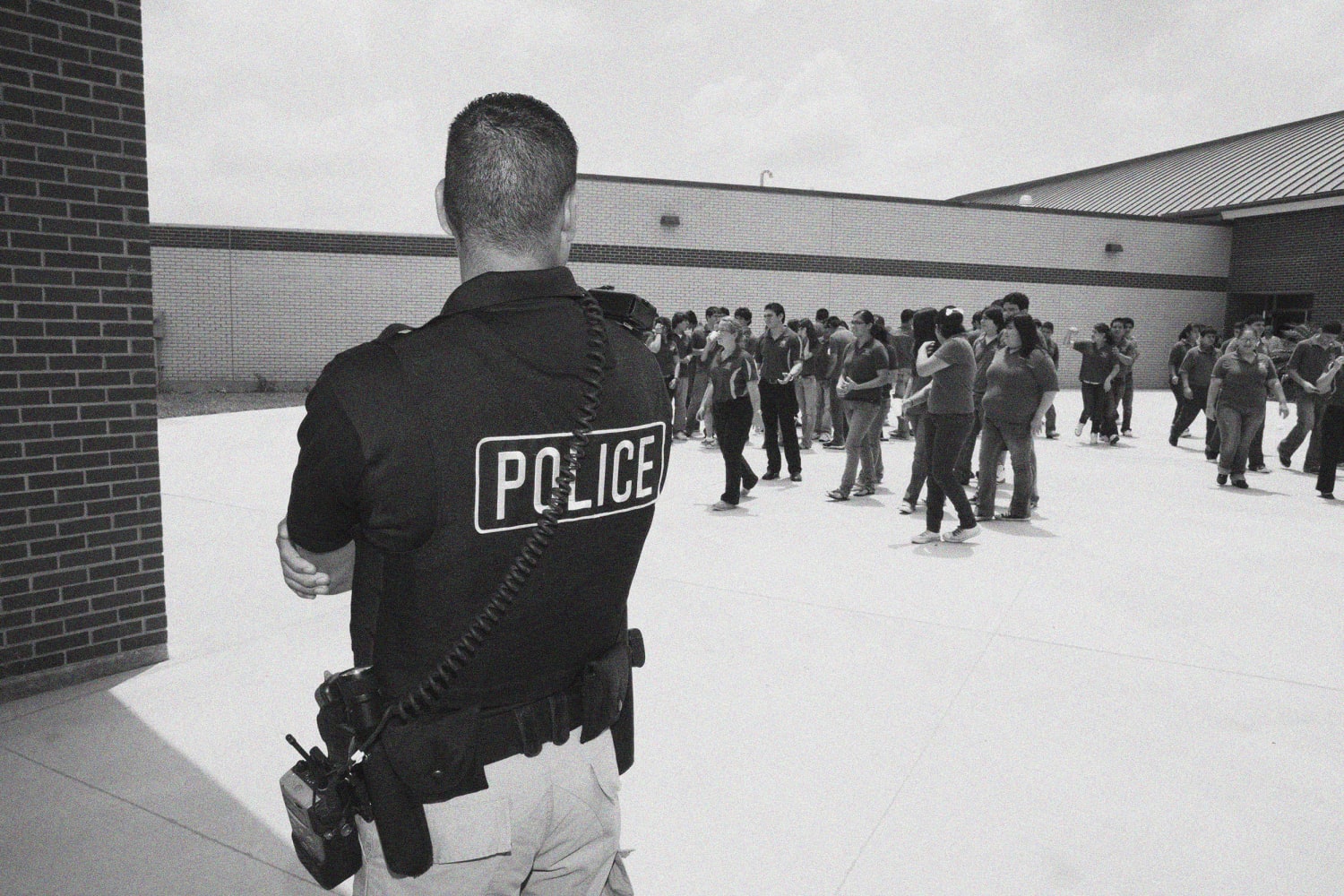

My councilman’s Facebook post read, “At the direction of County Prosecutors, the Attorney General, and the Governor of New Jersey, we will be increasing the presence of police at and patrols around our schools.”

I found no relief in this message.

I mourn for the lives lost and, inevitably, imagine a world where my children were among those slain.

The notice was a response to this week’s elementary school massacre in Uvalde, Texas, which took the lives of 19 children and two teachers. These moments — infuriatingly common in America — strike me, as the father of two, to the core. I mourn for the souls lost and, inevitably, imagine a world where my children were among those slain.

Not surprisingly, everyone is searching for answers to this unrelenting cycle of violence. But for many Black people, the idea of policing as a means of protection is a fallacy born of the privilege of whiteness. America has long existed within the binary of good guys versus bad guys. As James Baldwin put it: “It comes as a great shock around the age of 5, 6, or 7 to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you. It comes as a great shock to see Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, and although you are rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians are you.” In the American binary, Black people don’t get to be Gary Cooper, at least not without forfeiting a large part of their identity.

I am fortunate that my 15-year-old daughter and 9-year-old son have yet to have had any significant interaction with law enforcement. We live in a suburban town that strives to achieve all those liberal ideals, namely diversity, equity and inclusion. Of course, it fails as much as it succeeds — but there is comfort in the effort.

My daughter’s understanding of police brutality comes mainly from the media, particularly in the context of the protests that occurred throughout 2020. My son still believes himself to be Gary Cooper. Increased police presence in schools means more opportunities for police to come in contact with Black and brown students. And unfortunately, we already know what that means. According to the American Civil Liberties Union, Black and disabled children are the most likely to be referred to and arrested by law enforcement. The fact that our most vulnerable children are disproportionately subjected to police intervention is indicative of a tragically broken system.

Clearly, mass shootings and unjustified police shootings are two branches of the same rotting tree. They are the consequences of a white America still grappling with its own identity. And the myth of white exceptionalism has the country in a chokehold.

The 18-year-old man accused of taking the lives of 10 people in the recent mass shooting in Buffalo, New York, is alleged to have cited the so-called great replacement theory as a motive. The great replacement theory is a belief that has gone from the fringes of white extremism to center stage with certain pundits. Rooted in antisemitism, its tentacles target all races, sexualities and religions that don’t align with white supremacist ideals.

Mass shootings and unjustified police shootings are two branches of the same rotting tree.

Neither is the American legal system immune from this state of whiteness. Even if we set aside the active infiltration of white supremacists in our law enforcement and the military, there is still the issue of the disproportionate number of deaths of Black people at the hands of police. Black people are more than twice as likely to be killed by police than white people.

I say all of this with the understanding that Salvador Ramos, the young man responsible for the Uvalde tragedy, wasn’t white. Neither were most of his victims. But while it is understood that no race or gender is immune from birthing a mass shooter, white men are far and away the most likely to take part in mass shootings.

It’s not that other Black parents and I don’t want to be able to trust the police to defend our families, our way of life and our liberty. At the peak of the war on drugs, many Black people supported the 1994 crime bill hoping that more ardent policing and stiffer penalties would curb a drug epidemic that tore many Black neighborhoods apart. That hope was brutally crushed as, instead, Black families were torn apart.

Black people want to be safe. We want our children to be safe. More and more, however, identifying what is safe in the milieu of whiteness is not only difficult. It can be dangerous.

So what is the solution? I have spent the entirety of this essay saying why police aren’t the answer. The truth is I don’t know fully what is. I do know that this country keeps putting the same bandages on the same scars, and those scars never heal, all for the sake of donning a cowboy hat, strapping on a six-shooter and remaining the hero it never was.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com