Astrophysicist Natasha Hurley-Walker was scanning radio signals across huge swaths of the cosmos in late 2020 when she and her colleagues stumbled on something they had never seen before.

In a patch of sky that was monitored continuously over 24 hours, the scientists detected the appearance of a mysterious object that unleashed a giant burst of energy every 20 minutes or so and then disappeared several hours later.

“It was kind of spooky for an astronomer because there’s nothing known in the sky that does that,” Hurley-Walker, an astronomer at Curtin University and the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research in Australia, said in a statement. The researchers detailed the finding in a study published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

The observation is what’s known as a radio transient, which refers to an object that periodically releases brief flashes of radio signals, as if it’s switching on and off in space.

The occurrences have been seen before — usually as very quick events that flash on and off within seconds or milliseconds or as longer pulses that last days — but radio transients hadn’t previously been detected appearing and disappearing over a few hours, Hurley-Walker said.

More research is needed to figure out what’s causing the bursts of energy, but the astronomers think it could be a so-called magnetar, which is a special type of “dead” star with an ultrastrong magnetic field.

Hurley-Walker said the prospect of a repeating radio signal in space may cause some to think it’s a dispatch from aliens, but she said the observations spanned a wide range of frequencies, which indicates that they have a natural origin and aren’t some artificial signal.

The search began in 2020, when Hurley-Walker assembled a team to map radio waves in the universe using data collected in 2018 by the Murchison Widefield Array, a radio telescope in the Western Australian Outback.

Tyrone O’Doherty, an undergraduate student at Curtin University at the time, found the object by looking at Milky Way observations from March 2018 and May 2018 and searching for any differences. O’Doherty said he hadn’t expected to make such a fascinating discovery.

“It really feels quite surreal to have found something like this,” he said Monday in a news briefing.

To confirm the discovery, Hurley-Walker sifted through the Murchison Widefield Array’s extensive archives, which stretch back to 2013, to see whether the telescope had picked up any other activity from the object. She found that it had switched on in the first part of 2018, emitting 71 flashes of radio signals from January to March of that year, before it switched off again. As she and her colleagues saw in their own observations, the pulses came at regular intervals.

“It’s just every 18.18 minutes, like clockwork,” she said.

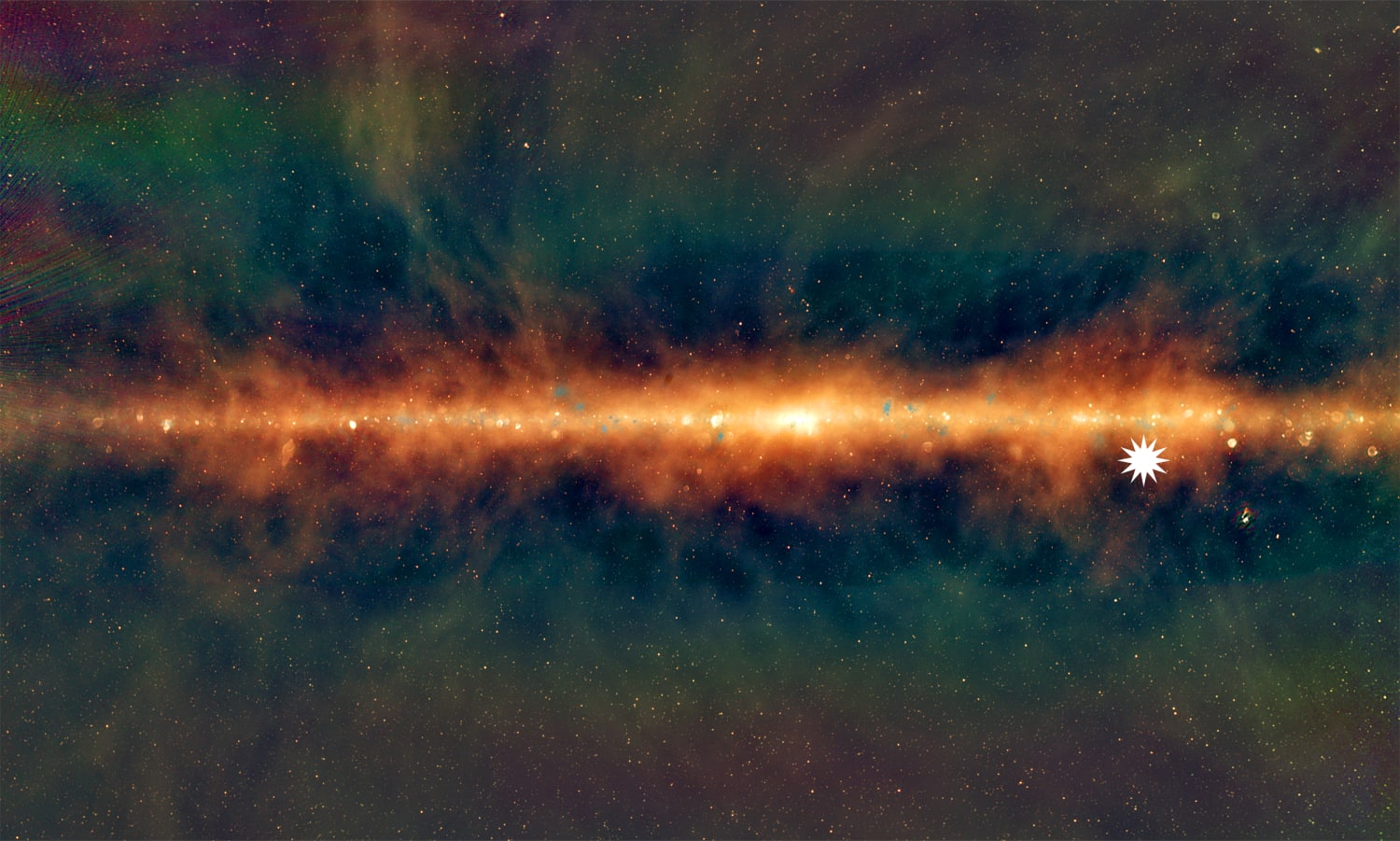

The astronomers determined that the object is about 4,000 light-years away and that it is likely to be a slowly spinning magnetar that is somehow converting energy from its magnetic field into light that can be detected by radio telescopes. Pinning the details down, however, will require observing the object when it’s active again or finding similar objects elsewhere in the Milky Way, Hurley-Walker said.

Kiyoshi Masui, an assistant professor of physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who wasn’t involved with the research, called it an “exciting” discovery that demonstrates how much remains to be understood about radio transients.

“There’s all this stuff that’s just waiting to be found,” he said.

Masui’s own research focuses on what’s known as fast radio bursts, which are mysterious single pulses of radio waves from other galaxies that have long mystified astronomers. Fast radio bursts seemingly occur at random, unleashing intense bursts of energy before disappearing.

It’s possible, Masui said, that the two phenomena are related. Magnetars are thought to be a possible source of fast radio bursts, but the links haven’t always been clear.

Magnetars are a type of dead star, or neutron star, that has burned up all its fuel and collapsed into a very dense spinning object with a powerful magnetic field. Magnetars are typically found only in areas where new stars are being born, but fast radio bursts have been detected away from stellar nurseries, sometimes in areas where there are only old stars, Masui said.

In their study, Hurley-Walker and her colleagues found that the newly detected object appears to be spinning much more slowly than other magnetars, which could indicate that it has outlived other magnetars that typically last only a few thousand years.

“If this object is, in fact, a magnetar, that could mean that at least some types of magnetars can survive much longer than we thought they could,” Masui said. “That could solve the thorn in the side of the magnetar hypothesis for fast radio bursts.”

Yet, Hurley-Walker said it could also be an entirely new type of cosmic object that caused the flashes of energy. Though the object appears to be inactive at the moment, she plans to continue to monitor the Milky Way with other radio telescopes and X-ray observatories in hopes of finding others like it. Building a catalog of similar occurrences could help researchers understand how they came to be.

“Because we didn’t expect this kind of radio emission to be possible, the fact that it exists tells us that some kind of extreme physical processes must be happening,” she said.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com