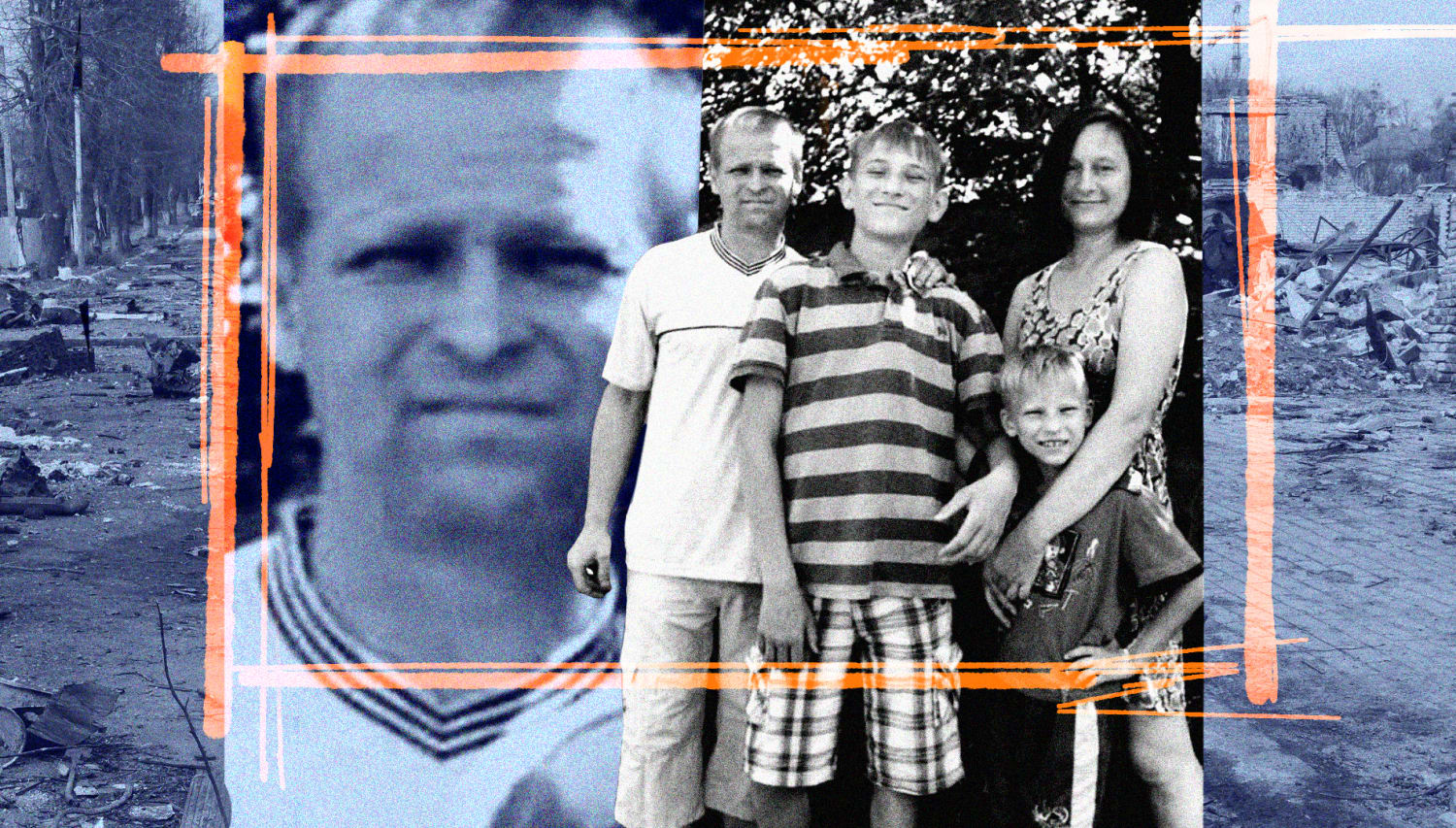

BUCHA, Ukraine — With machine guns trained on them, Natalia Kulakivska had just a few seconds to say goodbye to Yevhen Hurianov, her husband of 16 years.

She dropped down on the patio of the family house and they locked eyes as almost 20 Russian soldiers forced him to his knees.

“I hugged him, touched his cheek,” she told NBC News as she tried to hold back disobedient tears.

It was the last time she saw Hurianov, who went by the nickname “Zhenia,” she said around four weeks after he was taken away.

The soldiers had accused him of being in Ukraine’s territorial defense, a volunteer military unit of the country’s army. Kulakivska denies that. According to her, he is an ordinary civilian — a car mechanic who runs a family business with his brother and his stepfather from the garage in their backyard.

Watch “Unbreakable: Taken by Russia — Searching for Zhenia” on NBC News NOW Sept. 14 at 10:30 p.m. ET

While NBC News could not independently verify all the details of Kulakivska’s account, it squares with widespread stories of Russia’s so-called “filtration” operations.

The State Department said on Sept. 7, the U.S. it had evidence that “hundreds of thousands” of Ukrainian citizens have been forcibly deported to Russia in “a series of horrors” overseen by officials from Russia’s presidency — a charge Russia immediately dismissed.

Bucha, a leafy suburb of Kyiv where the couple shared a house made of brownstone, has become a byword for Russian atrocities. Moscow’s retreat from the area in early April after five weeks of occupation revealed a shocking scene of destruction and brutality: shattered buildings, burned-out cars and bodies strewn on streets. Investigators are examining the town’s mass graves for evidence of war crimes.

Moscow denies committing atrocities in Bucha, accusing Kyiv of orchestrating them to discredit the Russian army. In an email to NBC News, it called “accusations” of forced deportation “groundless” aimed at “discrediting Russia.”

‘I believe’

In the midst of the death that has surrounded her, Kulakivska is steadfast in her conviction that Hurianov is alive. Searching, and waiting, for him is an everyday quest.

But she isn’t just looking for her husband.

Around the time Hurianov was taken, she said, her sister’s husband, Serhii Liubych, 37, and 20-year-old son, Vlad Bondarenko, who lived in the nearby town of Hostomel, were also captured by Russian soldiers.

During the occupation, her sister, Snizhana Liubych, fled to Poland, taking her remaining children and Kulakivska’s children, Yevhen, 16, and Nazar, 10.

Kulakivska stayed behind to look for the three missing men, keeping a mental image of them coming home, walking through the front gate.

“I believe this is how it will be,” she said.

On April 21, a man did walk through her gate. But instead of her loved ones, it was a former police officer from the neighboring town of Hostomel, who had also been detained by the Russians.

The man, Oleh, later said in an interview that on March 20, he had been forced into a dark basement in an unknown location with other men. (NBC News is not publishing Oleh’s last name out of concerns for his safety.)

There, he met Hurianov, who offered him a place on the mattress lying on the floor.

“Zhenia turned out to be a great human,” Oleh said.

They spent what Oleh believes to be the next two nights in this pitch-black, cold space. He said they were given porridge twice a day that, in the absence of spoons, they were forced to eat with their hands. They were only allowed one toilet visit a day and “only if you couldn’t endure it anymore,” Oleh said.

The two men made a pact: The first to come back alive would find the other’s family and tell them what had happened.

After two days, Oleh said they were moved from the basement, blindfolded and handcuffed, and put on a truck along with other captives to be taken to Ukraine’s northern border with Belarus, Russia’s close ally. Eventually, they realized that Kulakivska’s nephew, Bondarenko, was also on the truck with them, Oleh said.

On March 23, in Belarus, Oleh and Hurianov were separated.

Oleh said he spent the next three weeks in a prison in Kursk, a western Russian city close to Ukraine’s eastern border, before being exchanged for Russian prisoners whom Ukraine was holding. The day after returning home, he found himself at Hurianov’s home.

Oleh told Kulakivska her husband was alive, at least as of March 23 when they were in Belarus together. He also believed that Bondarenko had managed to escape. He jumped off the truck they were transported in close to what Oleh thought was the Ukrainian town of Chernobyl, near the Belarusian border.

For days after learning this from Hordiychuk, Kulakivska was holding onto the hope that Bondarenko was alive. But then, on April 26 a post on the Telegram messaging app, spotted by her sister from Poland, once again turned the family’s life upside down.

Kulakivska said she later learned that her nephew’s bullet-ridden body was found by the locals. Then after the Russian forces retreated, his body was exhumed.

Kulakivska had to FaceTime her sister in Poland from the morgue to help identify Bondarenko’s body, an experience she said was painful “beyond words.”

‘Hardest thing is to wait’

There are many like Kulakivska in Ukraine — those whom the war has forced to wait for loved ones who may never return. The forcible transfer of civilians is a serious violation of the laws of war amounting to a war crime and could be a crime against humanity, according to the United Nations. In June, the country’s government said that 1.2 million Ukrainians had been deported to Russian territory in this way.

In July, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that Russian authorities have “interrogated, detained, and forcibly deported between 900,000 and 1.6 million Ukrainian citizens, including 260,000 children, from their homes to Russia.”

The Geneva Conventions, which spell out international rules intended to protect combatants and civilians in armed conflicts, state that “individual or mass forcible transfers, as well as deportations of protected persons from occupied territory to the territory of the occupying power or to that of any other country, occupied or not, are prohibited, regardless of their motive.”

Russia denies targeting or mistreating civilians.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com