On Tuesday, reigning Olympic champion Simone Biles surprised the world when she withdrew from the women’s team gymnastic final over mental health concerns. On Wednesday, she announced she wouldn’t be participating in the marquee women’s all-around final either. Her decision came just days after saying she felt as though she had “the weight of the world” on her shoulders. Following her team’s second-place finish, Biles broke down in tears as she addressed the media, explaining she was not in the right place mentally to perform. She also reminded everyone watching that those competing are not “just athletes, we’re people at the end of the day.”

Is mental wellness even feasible given the amount of intense public scrutiny and expectation to perform perfectly?

She’s right — and she’s not alone. Right now, we are witnessing a tremendous paradigm shift in how we view, diagnose and treat mental health concerns among athletes. An entire generation of elite athletes has begun to speak openly about the unique pressures they face: Tennis star Naomi Osaka, Olympic sprinter Noah Lyles, Olympic gold medal-winning swimmer Simone Manuel, shot-putter Raven Saunders and gymnast Sam Mikulak are just a few who have stepped forward to bring their mental health experiences into the spotlight.

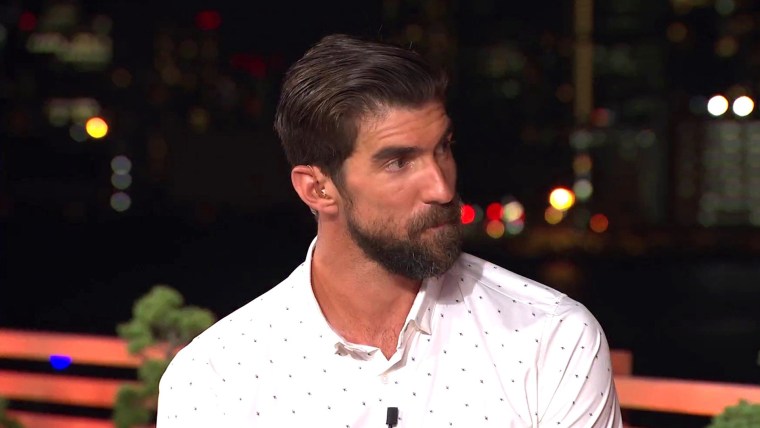

And they are following in the footsteps of Olympic giants like Michael Phelps, who has been candid about his struggles with depression and suicidal thoughts, including producing an HBO documentary in which he and other Olympians talked about mental health challenges, and Lindsey Vonn, who has continued to shed a light on her decadelong battle with mental illness.

This discussion is crucial, and overdue. But it also begs a more fundamental question: For Olympic athletes, whose entire careers are based on performing under immense pressure on a global stage, is mental wellness even feasible given the amount of intense public scrutiny and expectation to perform perfectly?

As a college president of student-athletes who play in the Division I Ivy League, and a former soccer and lacrosse player myself, I see firsthand the pressures young athletes face. And as a cognitive scientist who has spent decades focused on the psychology of sport, I’ve researched at length the stresses that athletes undergo, particularly in the moments that matter most in high-stakes competitions.

What my research shows is that athletes are not born “chokers” or “thrivers.” Instead, even the GOATs have to practice psychological strategies (ranging from positive self-talk to meditation to mental imagery) to perform at their best in pressure-filled situations. They also have to be constantly focused on their own mental wellness and take steps — such as turning down post-game interviews when they don’t feel like talking — to ensure that it is protected. Only then are athletes able to perform at their best and feel good doing it.

Athletes are forced by the nature of their discipline to lose — to fail — very publicly. But the challenge posed by that immutable reality is made considerably worse by their public treatment in our modern media environment. When we expect them to dwell on and dissect their shortcomings — through post-game press conferences, extended interviews and social media livestreams — in the name of continued entertainment, we are also inherently causing them added stress that can further impact their performance.

My research looked at golfers to better understand why individuals “choke under pressure,” and what I found is that well-practiced athletic performance becomes more of an exercise in physical memory and repetition as opposed to a conscious way of moving. Even the most skilled athletes were unable to accurately describe what they did in order to sink a tournament-winning putt. Indeed, athletes that are the most successful at performing at a high level actually stop paying attention to the step-by-step details of what they are doing and are not able to tell others how they do what they do.

So when high-level athletes are asked to focus on the details of their performance, they can screw up. They can also stress out. And this stress and anxiety is not always short-term. Worrying doesn’t just go away when a competition is over — we often ruminate after the fact. Left unchecked, athletes will carry these worries with them from one competition to the next, where they can pop up and disrupt their performance unexpectedly.

Another big source of anxiety, for everyone, is uncertainty and not knowing what is to come. After a year and half of unprecedented challenges and dealing with the unexpected due to Covid-19 — which pushed back the Olympics by a year and threatened to cancel it altogether — it’s no wonder some athletes are starting to say “enough.” Athletes control their environment as they can, and one way is not talking to reporters or even withdrawing from competition.

This information should be motivation to dial back the media circus that is often associated with high-level sporting events. As Naomi Osaka recently suggested in Time, we “should give athletes the right to take a mental break from media scrutiny on a rare occasion without being subject to strict sanctions” like the fines she faced after bowing out of recent interviews. Perhaps athletes, coaches and the press could agree ahead of time if and when interviews will occur, the format of these interviews and how many will take place. And when an athlete doesn’t feel like talking, press, fans and sporting bodies alike should work to respect that.

It’s also important that we as the consumers of media and audience for these athletic events appreciate progress alongside perfection. Psychologist Carol Dweck has found that individuals who carry a fixed mindset of success — such as an athlete focused on the strict binary of either winning or losing — tend to perceive single failures as being far worse than they actually are. Other studies have confirmed that when our failures are made public, we are more likely to view them as catastrophes as opposed to simple setbacks.

We can combat this phenomenon by spending more time celebrating athletic achievements that demonstrate growth and progress in addition to those that are the best of the best. Biles may have “only” won silver in these Games, but she’s also been attempting never-been-seen moves in her routines. Surely that is something worth deeming a success?

It’s time we dismantle the social stigma surrounding mental health, whether that’s at work, at home, on the field or in a gym. It’s time we stop expecting athletes to be media commentators on their own performance, whether good or bad. It’s time we prioritize mental health services such as therapy among athletes and ensure they have the tools and resources they need to properly manage their mental health, whether that is implementing effective stress management strategies, carving additional breaks into their training schedules or creating a better diet plan. Perhaps most importantly, it’s time we start viewing vulnerability as a strength rather than a weakness, even among our athletic superheroes.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com