The city official tasked with overseeing the production of the list expressed concern that publishing it could prematurely cause uneasiness among tenants, investors and others before building owners have a chance to do thorough evaluations.

The existence of the list was previously reported by KPIX-TV and the San Francisco Chronicle, but its actual contents have never been published before. A city website said the city had “created an inventory of concrete buildings,” although someone removed that mention after an NBC News reporter requested a copy.

The list is preliminary, so buildings could be taken off or added as city workers learn more about specific locations, and the San Francisco Office of Resilience and Capital Planning said that the dataset “will contain inaccuracies.” The list excludes single-family homes, public schools and buildings constructed after 2000. It’s not clear when the list will be finalized, but structures on the current list have one thing in common: They were built with concrete at a time before engineers fully understood how much steel or other reinforcement was needed to keep the concrete from crumbling while shaking. The concrete, referred to as nonductile concrete, breaks rather than bends in response to stress.

David Friedman, a retired structural engineer who’s a volunteer member of a city working group on the subject, said: “These buildings, when they get damaged, they can get damaged to such a degree that they lose their vertical load-bearing capacity and they collapse.

“These buildings will kill people if we’re not careful,” he said, referring specifically to the risk of buildings collapsing in a major earthquake before they’ve been retrofitted.

The only way to know a building’s safety level for certain is to have a qualified structural engineer evaluate it, the Resilience and Capital Planning office said. Engineers said the cost of that evaluation alone could be tens of thousands of dollars per building.

Brian Strong, San Francisco’s chief resilience officer who oversees city policy and programs for earthquake safety, said in an interview that the city is determined to make the buildings safe but also believes it will take time because of the enormous cost involved. The process involves a lot of uncertainty about which buildings are truly vulnerable, he said.

“There are no easy answers. It’s a complex problem with a lot of complex answers, but it’s something we know we have to do,” Strong said.

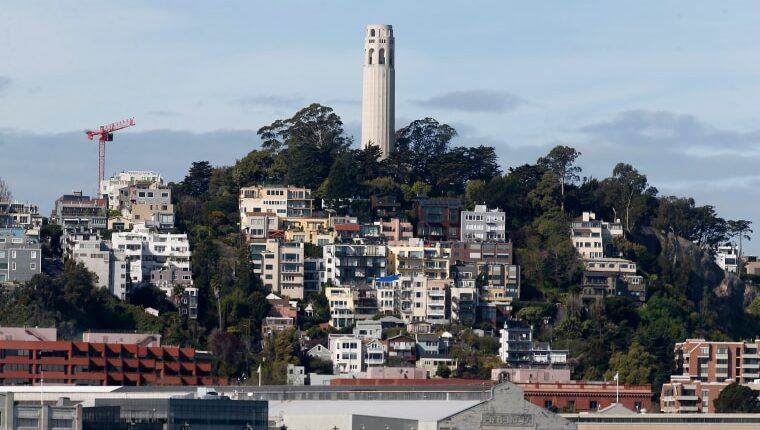

The building inventory touches rich and poor alike and the diverse communities within San Francisco: from low-income senior housing in Chinatown to the landmark Coit Tower that overlooks the North Beach neighborhood, from the city’s former stock exchange where there’s a 1931 fresco by Diego Rivera to the massive art deco building where Twitter has its headquarters (listed under an alternate address that is not currently in functional use).

Other addresses on the list are historic properties, including the Castro Theatre movie palace from 1922 that’s a center of LGBTQ life, and the hilltop Fairmont hotel that’s appeared in films and television. A six-story apartment building directly adjacent to the city’s famed “painted ladies” Victorian and Edwardian homes is on the list, and so is the corporate headquarters of retailer Williams-Sonoma.

The Chinatown Community Development Center, which operates at least three affordable housing buildings on the list, said that it had recently strengthened them to comply with existing city requirements and wasn’t sure how a possible concrete retrofit program would affect them.

“We would, of course, be disappointed if the City adopts a new standard that requires significant and expensive changes unless that standard significantly improves safety,” Whitney Jones, deputy director of the center, said in an email.

Shorenstein Properties, owner of the Twitter headquarters building, declined to comment. The Fairmont declined to comment. NBC News contacted the owners or operators of the other buildings named above for comment and did not immediately hear back.

Strong said he and other authorities have been hesitant to publicize a list of possibly risky buildings until they have more time to verify that the buildings on it are truly at risk.

“This is a list that has not been verified,” Strong said. “It’s a draft list of buildings that we think may be in the program, and we’re trying to cast a broad net to ensure we’re not missing anything.”

Strong said that releasing the inventory too early would risk unfairly reducing the value of some buildings, or causing unwarranted anxiety for tenants. His office, though, provided a copy of the inventory in response to a public records request.

“I know there’s a fear out there that we’re going to ask people to retrofit their buildings in the next four or five years,” he said. “We expect it’s going to take many years for the building owners to comply.”

Engineers have known about the concrete vulnerability since 1971, when a newly built concrete hospital in Southern California partially collapsed in an earthquake. But San Francisco is only now responding, following a 2011 work plan that gave priority to work on other types of vulnerable buildings. The 2011 plan anticipated that mandatory evaluations of older concrete buildings would begin in 2015, but that hasn’t happened yet.

Engineers who specialize in earthquake risks are increasingly nervous, following recent building collapses in the U.S. and Turkey.

Concrete buildings constructed before 1980 would account for half of the deaths in San Francisco if a magnitude 7.2 earthquake were to hit the nearby San Andreas fault, according to a 2010 study done for the city. The percentage would be even higher if the earthquake happened during the day while people were at work, the study found.

The study said 200 to 300 people could be killed in such an earthquake and 7,000 seriously injured, though it added: “Casualties could be much higher if even one large, densely occupied building collapses.”

Replacing all those buildings would cost around $19 billion, the study said, using 2009 dollar values. That’s about $27 billion in 2023 dollars.

In February, San Francisco and other cities got a reminder of the danger from a series of earthquakes in Turkey and Syria. More than 50,000 people died in those earthquakes, many of them in collapsed or damaged buildings with insufficiently reinforced concrete.

“People in Turkey were saying, ‘How come I wasn’t told that these were vulnerable buildings?’” Friedman said. “We’re on borrowed time and we need to get these buildings fixed.”

The most severe earthquake in Turkey was magnitude 7.8, and the 1906 earthquake that devastated San Francisco was magnitude 7.9. There’s a 20% chance that an earthquake measuring magnitude 7.5 or worse occurs in the San Francisco Bay Area in the next 30 years, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Concrete buildings in the U.S. received attention in 2021 after the collapse of a condo tower in Surfside, Florida, but the problem in San Francisco and other earthquake-prone areas is different. Rather than delayed maintenance, it’s about the design of the structures and how they’d fare under intense shaking.

The cost of addressing the risk comes at a bad time for San Francisco. While many of the city’s neighborhoods are as vibrant as ever, the pandemic has hollowed out the downtown core as corporate tenants, including Meta and Salesforce, vacate office space, and retailers, including Nordstrom and Whole Foods, eliminate locations.

The result has been a steep drop in the value of commercial real estate in the city. Wide recognition of the earthquake risks of older concrete buildings could be another blow.

The cost of fixing a structure could be $150 to $200 per square foot per floor, which could easily run into the millions of dollars for some individual buildings, engineers said. The price tag for a 71-unit concrete apartment building that’s already had structural retrofitting completed was $15.5 million, or $130 per square foot, said Leo Panian, the structural engineer who worked on the job. With nonstructural costs like interior finishes, the total cost was $20.6 million, or $173 per square foot.

The reason the fix can be so costly is because it’s invasive. It requires adding new layers of concrete, steel, carbon fiber or other material spanning the building’s height and footprint, as well as repairing interior finishes destroyed in the process.

It could be so expensive that some owners will choose a wrecking ball, said Robert Kraus, a structural engineer in San Francisco who helped create the inventory of the buildings.

“This will lead to some buildings deciding it’s easier to just redevelop,” Kraus said.

Some people doubt whether the local economy will be able to shoulder the cost of making the buildings safe at a time when the city is already in a dire financial situation.

“I don’t know how this is going to get done, frankly,” said Janan New, executive director of the San Francisco Apartment Association, a trade group for the city’s landlords.

The city isn’t promising to help pay for the work, and the cost of private loans is going up, she said.

“I think there’s an overall acknowledgment that we need to do it,” she said, but added: “We’re in a very serious economic climate right now where there is not a lot of funding available for this work.”

In 2017, condo owners in West Hollywood, a city in Los Angeles County, were so aghast by the cost that they lobbied their city council to make concrete retrofits voluntary — a decision that relieved them of the cost but not the danger.

In San Francisco, it’ll be up to the city’s mayor and board of supervisors to decide whether to make retrofits mandatory, and if so, what the deadline should be. Engineers expect property owners to have decades to comply.

The list of vulnerable buildings includes many addresses associated with vulnerable populations. The highest concentration of buildings is in one of San Francisco’s poorest neighborhoods, the Tenderloin, and at least four buildings on the list are large, multi-story apartment houses for low-income tenants who may not have anywhere else to go.

Megan Stringer, president of the Structural Engineers Association of Northern California, said updating the buildings could be so disruptive that tenants often won’t be able to stay in their homes or offices while it happens.

“You’re talking about people potentially needing to be displaced while the retrofits are happening, and that’s not something people want to hear,” Stringer said.

“It’s invasive and it’s expensive, so you can imagine it would be a sensitive topic for building owners and occupants of the buildings,” she said.

Maria Zamudio, organizing director of the Housing Rights Committee of San Francisco, which counsels tenants on their rights and advocates at city hall, said: “The San Francisco housing stock is an older housing stock, and the older a building is, the more likely it is that it has low-income tenants.”

Zamudio said most renters have no idea of the concrete-related risk or of the chance that they might need to relocate during a retrofit.

“Everyday tenants are still trying to recover from the impact Covid had on their lives and financial situations,” she said. “Folks are really just still worried about their rent.”

Behind the scenes, advocates are pushing the city to improve its notification to tenants about their right to return after a retrofit. They also want to prevent landlords from passing on the cost of retrofits to tenants in rent-controlled units, while landlords are lobbying for the right to do so.

There’s no uniform rule for when and how government agencies should share earthquake risks with building owners and tenants. San Francisco has a searchable online map of 4,900 wood-frame buildings that are or were vulnerable because of a “soft” or poorly supported first story, and it could do the same for concrete buildings in the future. More than 90% of the soft-story buildings are in compliance with a 2013 city ordinance requiring retrofits.

In 2013, Los Angeles residents frustrated by a lack of transparency began speculating about a “killer buildings” list as city officials there debated what to do about vulnerable concrete buildings. Los Angeles passed a city ordinance in 2015 mandating that certain concrete buildings be retrofitted and has a website for people to search addresses. Property owners have 25 years to complete the work or demolish their building.

Friedman said he expects property owners to have a range of responses once they find out, from head-in-the-sand denial to eagerness for a fix. Either way, he said, finding out is inevitable.

“I really want the public to be able to have some confidence and have some disclosure of which buildings are hazardous,” he said.

“At some point we need to alert people and require people to abate the risk of these very dangerous building types,” he added.

Even creating the list for San Francisco has been a complicated process. City staff and volunteers began in 2018 by poring over 1,200 paper maps from the 19th and 20th centuries that people created originally for fire insurance underwriting purposes and later annotated by hand over several years. They then checked the data against information from other sources, such as the city assessor’s office or observations from the sidewalk.

And even still, there’s a limit to what the inventory can reveal. Engineers said the only way to accurately gauge a concrete building’s risk is for an engineer to do an on-site study, which may involve opening walls to see how they were constructed.

“You can’t walk up to a building and know how it’s going to perform or what its vulnerabilities are,” Kraus said.

That uncertainty has caused some people to overlook the urgency, he added.

“This is a vulnerable building type,” he said. “We’ve known it going on 50 years, and that knowledge has not translated into action because of the cost and the effort that goes into a retrofit.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com