On the first day of school, my first grade teacher instructed us that if we heard our parents playing music at home, if they had certain books of poetry on their shelves, if they drank wine, if they danced, if they invited friends over, if our mothers dressed immodestly, if our fathers listened to unsanctioned radio stations, if we saw our school friends at the park without hijabs, we should report these things to her immediately. A good student followed the rules of Islam.

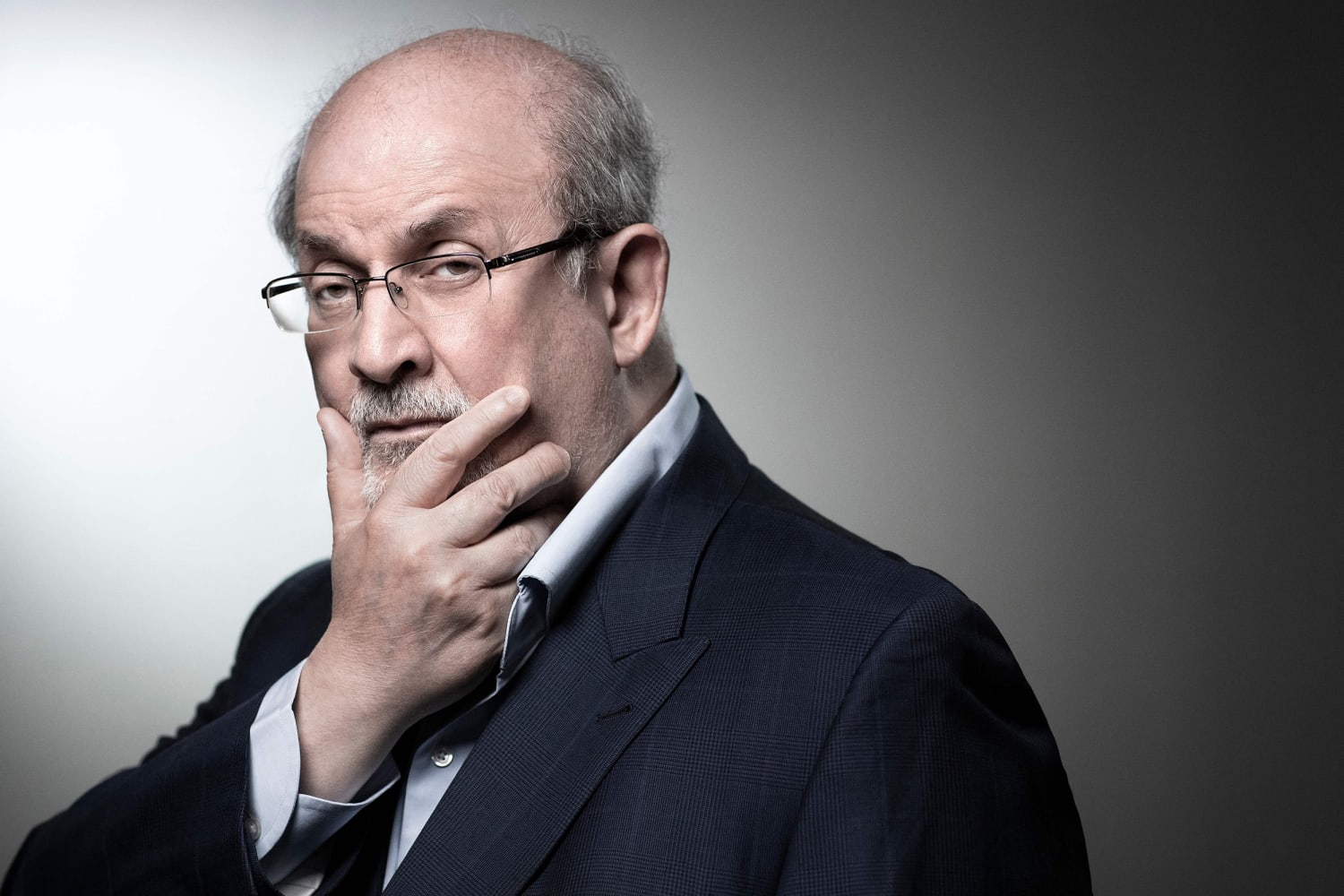

What happens in a society where freedom of expression and the open exchange of ideas are silenced? “It becomes impossible to think,” Rushdie explained.

I wanted to be a good student. I wrote my alphabet with meticulous handwriting in my state-issued notebook so that she might give me a star. I stood in the school line on cold autumn mornings and swore my allegiance to Islam and the supreme leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. I recited the names of the 12 imams of Shia Islam in front of the class. I walked straight home from school passing young men with guns who volunteered their time to police morals and arrest dissidents.

In the evenings, my parents spoke in whispers while I did my homework, until one afternoon they told me I wouldn’t return to school the following day, that we were leaving Iran. I worried about missing class and not learning how to read. My father assured me that I still would as he packed my notebook in the single suitcase we were taking. In the lining, he also hid two volumes of poetry, a book by Sohrab Sepehri, another by Forough Farrokhzad.

In America, I practiced my cursive on worksheets. My father listened to the radio each evening. My parents invited friends over. Sometimes they danced. Sometimes they read poetry. There was always music. By and by, I learned to write words, and then, in one moment, I learned to read. I sounded out the same paragraph, over and over, until suddenly the words opened themselves for me and there I was, in an attic with a girl named Anne, hiding.

One evening, my father asked me if I knew of a writer named Salman Rushdie. “I would like to buy his book,” he said. I asked him why, since he couldn’t read well in English. “Perhaps you can read it and tell me what he has to say,” he told me. My father was raised Muslim. I have a picture of him as a little boy on a pilgrimage to Mashhad to pray at the shrine of Imam Reza. He wanted to read what Rushdie had written, to come to his own conclusions, to understand why Iran demanded the silencing of this author after his book “Satanic Verses” came out.

Shortly after its publication, and soon before Khomeini’s death in 1989, someone had told him that the book made the Prophet Muhammad seem irreverent and insulted the prophet’s wives by naming prostitutes after them. The supreme leader issued a fatwa calling for Rushdie to be killed. Twenty countries banned the book. A Japanese translator of “Satanic Verses” was murdered and three others were attacked. Riots over the book left 45 people dead, 12 of whom perished in Rushdie’s hometown of Mumbai. Copies were burned in the streets and bookstores were firebombed.

Rushdie went into hiding under the protection of the British government for nearly a decade. More recently, he has managed to lead a relatively normal life in New York. During all that time, he has spoken extensively about the freedom of expression. Indeed, the conversation scheduled to take place on the stage in Chautauqua, New York, where he was stabbed Friday, was meant to be about the United States as a refuge for the freedom of creative expression.

After the attack, when I told my mother I wanted to write something about Rushdie, about silencing, about the sanctity of the written word, she pleaded with me not to. “It’s too dangerous,” she said. “You don’t know what they can do.” She carries this fear from the country we fled. There, journalists are imprisoned. Writers are killed.

But the silencing of writers by the state is slowly becoming a reality in America, too. This fall, school districts across the country are pulling books with “sensitive material” out of their curriculums. Librarians are asked to remove volumes from their shelves or risk losing funding. Teachers are forbidden from teaching certain topics in their classrooms or risk being fired and are, in at least one state, facing criminal prosecution.

The same week of the attack on Rushdie, the board of a Utah school district decided to “temporarily restrict” access to 52 books, many of which address gender, sexuality and identity. Last year in a school district in California, officials disallowed any text that uses the N-word, leading to a handful of books being removed from the curriculum, including Martin Luther King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” in which he uses the word to define its abusive nature.

And the government isn’t the only entity suppressing free speech in America. Rushdie and some 150 other writers, addressing the current climate of “cancel culture,” stated in an open letter published in Harper’s Magazine in 2020 that “an intolerance of opposing views, a vogue for public shaming and ostracism, and the tendency to dissolve complex policy issues in a blinding moral certainty” is equally detrimental to the freedom of expression. On one hand, books about being gay are banned from American schools and libraries; on the other, author J.K. Rowling’s statements on gender, which many LGBTQ advocates find offensive, culminate in death threats on Twitter.

What happens in a society where freedom of expression and the open exchange of ideas are silenced? “It becomes impossible to think,” Rushdie explained in a 2006 interview, “it becomes impossible to have any kind of interchange of thought in a society if you are told there are ideas which are off limits.”

Much will be made of the young man who stabbed Rushdie. Was he radicalized on his monthlong trip to Lebanon to visit his father? Was his act inspired by Khomeini’s fatwa? This New Jersey man, raised in America, how was he corrupted? Fingers will undoubtedly point East.

To bridge this defensive, separated world that America has become, we need the freedom to express our ideas without the fear of being silenced, shunned, persecuted, fired, shamed, banned.

But there are so many young men in America like him, committing atrocities in schools, in supermarkets, in movie theaters, at parades, all in the name of their convictions. The argument shouldn’t be about the nature or the origin of the ideology. Instead, we should ask ourselves what absence of varying, diverse views left them feeling alienated. What echo chamber of dogma bred such rigidity of thought? In response to the London bombings of 2005, Rushdie wrote, “from such defensive, separated worlds some youngsters have indefensibly stepped across a moral line and taken up their lethal rucksacks.”

The miracle of the moment when I learned to read was not a matter of fluency, it was the shattering of a wall. When I entered that attic through a book and looked out of the window beside that hidden girl, I learned something I would never have otherwise known. Books should be triggering, they must shake us to our core, beat at the edifices of our ideas and send them crumbling down so that we can build better, stronger, more complex ones. Dialogues need to cause dissonance, moments that force us to hold conflicting beliefs because it is precisely in these moments of discomfort that learning happens.

To bridge this defensive, separated world that America has become, we need the freedom to express our ideas without the fear of being silenced, shunned, persecuted, fired, shamed, banned. Rushdie explains that we construct our identities through grand narratives, how the idea of nation and family and community are all stories — and the “definition of any living, vibrant society is that you constantly question those stories, you constantly argue about it. In fact, the argument never stops, the argument itself is freedom.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com