Drake Wuertz came to the school board meeting in Seminole County, Florida, in late June with a message familiar to those who had heard him speak at previous meetings: America’s children are at risk of systemic abuse.

And the way to stop it is to run for local office.

“They’re being carried away through our education system, through the woke ideology that’s infiltrated professional sports, through the sexual grooming and pedophilia that’s apparent in the entertainment industry,” Wuertz, 36, said in a video of the Seminole County School Board meeting posted by the district’s YouTube account. “We need to run for precinct committees, we need to run for City Council, run for school board and primary the RINOs in this room,” he said, using an acronym for Republicans in Name Only.

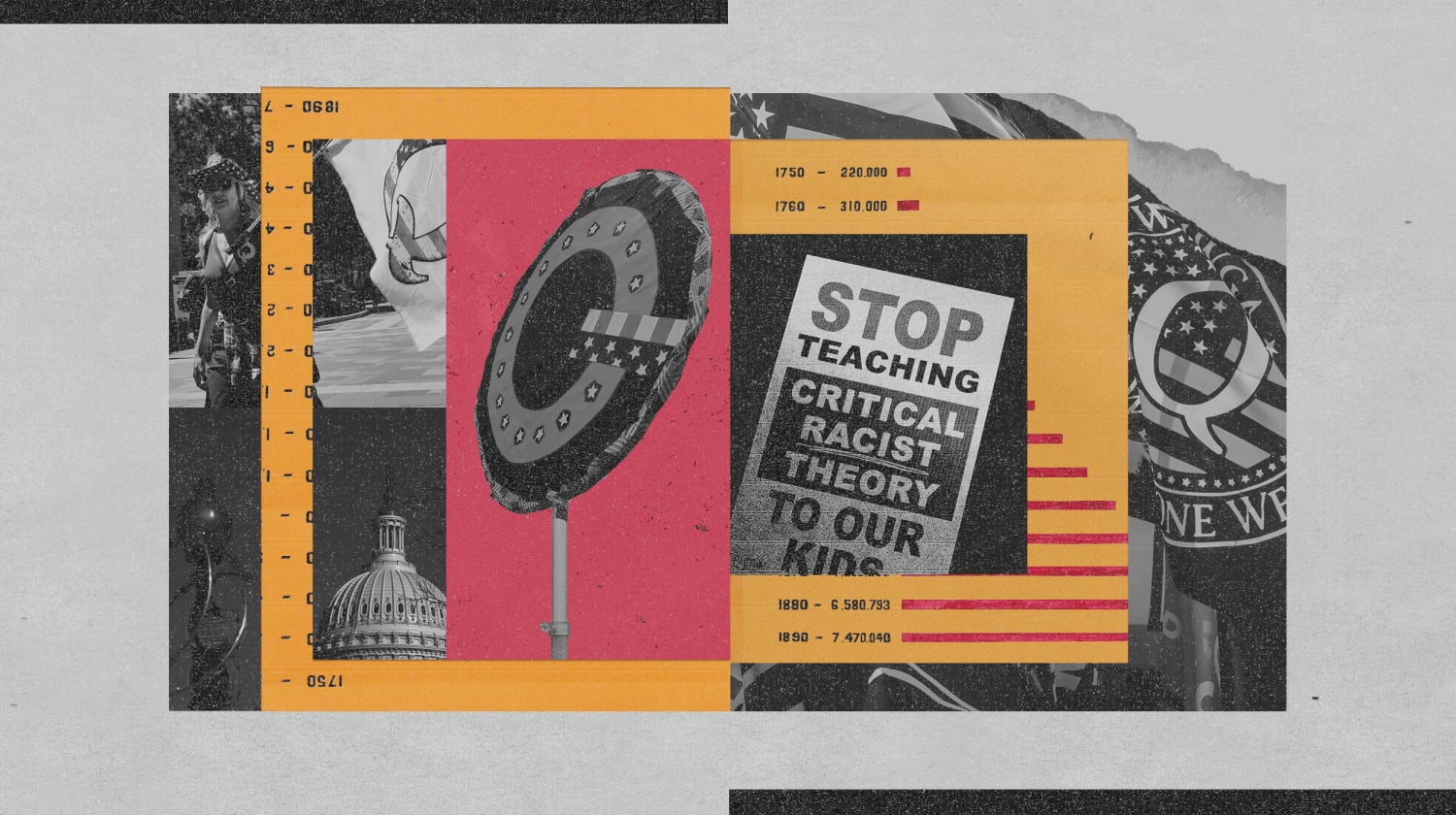

It was the kind of claim he’d made before, touching on a wide variety of fringe theories about sex trafficking, including the false conspiracy theory that mask mandates “make it easier for sex traffickers to target kids in our community.” On his social media profiles in the last month, Wuertz posted pictures of Michael Flynn, the former general and national security adviser, and the “great awakening” — all hallmarks of the fringe QAnon conspiracy theory.

But like many people who have trafficked in QAnon material, Wuertz has begun to distance himself from the movement.

“I can tell you that I 100 percent don’t subscribe to Q theories. Q theories hurt the mission of fighting sex trafficking and bring negative attention,” Wuertz said in an interview. Wuerz also denied making comments in the most recent school board meeting about masks being used by child traffickers and declined further comment.

In the wake of Donald Trump’s 2020 election defeat and the disappearance of the anonymous online account “Q” that once served as QAnon’s inspiration, many people who spout QAnon’s false claims have hatched a new plan: run for school board or local office, spread the gospel of Q, but don’t call it QAnon.

It’s a scene that has played out at other school boards and comes as many local meetings have emerged in recent months as cultural flashpoints in a broader battle over the perceived encroachment of race-conscious education — sometimes separately lumped together under the label critical race theory.

In California and Pennsylvania, people who previously espoused QAnon have run for school board positions, sometimes melding conspiracy theories with anti-CRT sentiment. In June, the National Education Association, a prominent teachers union, warned that “conspiracy theorists and proponents of fake news are winning local elections. And their new positions give them a powerful voice in everything from local law enforcement to libraries, trash pickup to textbook purchases.”

These moves signal an important evolution for the QAnon movement, which has fractured since Trump’s defeat, with many proponents rejecting the Q label but continuing to push ideas about societal conspiracies of child abuse. For the past month, the top of the Great Awakening, a leading online QAnon forum that calls itself the “public face of Q,” has featured an abridged quote attributed to Flynn, Trump’s first national security adviser and a hero to QAnon followers, who has sworn an oath to the community in the past.

“Local action = national impact. Take responsibility for your school committees or boards. Get involved in the education of our children. Run for local, state and/or federal office,” it reads. “No more excuses.”

QAnon followers have largely ditched the toxic QAnon branding, in part due to a post by Q last fall that read, “There is Q. There are Anons. There is no QAnon,” according to Mike Rothschild, author of “The Storm Is Upon Us: How QAnon Became a Movement, Cult, and Conspiracy.” Another post by Q in September implored followers to “camouflage” themselves online. At a recent event held by some of QAnon’s stalwarts, including Flynn, organizers sought to downplay the theory while still embracing its slogan.

And in recent months, some QAnon followers have shown signs of losing trust in “the plan,” which evolved in recent years into various strains but centers on the belief that Trump would secretly take down a fictitious group of Satanic, child-eating cannibals that ran the United States government. To QAnon followers, posts by a mysterious insider named “Q” left coded hints about the plan’s progress until “the great awakening,” the day when there would be a mass arrest of many prominent Democrats and A-list celebrities.

Posts on QAnon message boards that include the phrase QAnon are now frequently met with nudges that the community is no longer using the term for its movement.

Bans and crackdowns on QAnon by most major social media platforms including Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Amazon have further minimized the use of the term.

Rothschild said the Q posts were part of an effort to distance the conspiracy movement from real-life acts of violence and “Save the Children” rallies that were attributed to QAnon over the last year.

“If you identify as QAnon, people look at you like you’re crazy. But if you passionately talk about how we need to be saving children and protecting them from trafficking, then you come off as a compassionate person who really cares about the welfare of children,” Rothschild said. “You’re no longer one of those crazy cult people who thinks Hillary Clinton is trafficking kids in a tunnel under Central Park.”

Rochelle Keyhan, CEO of the anti-human trafficking organization Collective Liberty, told NBC News that the idea that masks are a boon for child sex traffickers portrays a misunderstanding of how human trafficking usually works.

“The narrative that children are kidnapped instead of lost and overlooked is appealing, because the reality is even scarier. Ultimately, because children can be more trusting and easily coerced, all children are susceptible to the manipulative tactics of traffickers,” Keyhan said.

Wuertz’s denial of QAnon mirrors those of other people who have become active in local politics. In June, students in Grand Blanc, Michigan, demanded the resignation of school board member Amy Facchinello after it was revealed she showed persistent support for the conspiracy theory on her social media account. One post, discovered by student Lucas Hartwell, read “Q ANON CONFIRMED BY TRUMP,” and numerous other tweets included the QAnon motto “WWG1WGA,” or “where we go one, we go all.”

When asked about the posts, Facchinello, who was recently elected to a six-year term and said she does not plan to resign, told The Michigan Advance, “There’s no such thing as QAnon.”

Rothschild said it’s part of a shift in how the QAnon community now views its mission: stop waiting for the prophecy to come true, and make it happen by winning off-year, low-turnout local elections.

“QAnon traditionally was top down. It was, at its heart, Donald Trump tweeting, ‘My fellow Americans, The Storm is upon us,’ followed by hundreds of thousands of arrests. They know now that’s not happening,” Rothschild said. “The prophecy around which QAnon was built is now done, but this movement now is bigger and stronger and more vocal than ever. So rather than just abandon it, they are changing it. They’re rewriting it on the fly. And now it’s really coming from the bottom up.”

It’s a strategy that has been embraced by some of QAnon’s most ardent and notable proponents.

In April, Tracy “Beanz” Diaz, one of the first and most prominent promoters of the QAnon conspiracy theory, won an election in Horry County, South Carolina, to join the state GOP’s executive committee, receiving 188 total votes.

Diaz was endorsed by Flynn, who had been telling his followers to take over school boards for months, including at a Reopen/Reawaken America tour event in June, headlined MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell, who emerged as one of the most vocal Trump supporters in claiming that the election had been rigged.

“We cannot allow school boards to dictate what is happening in our schools,” Flynn told the crowd. “We dictate that.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com