Emergency driving is an often dangerous part of modern policing. Even though police departments in recent decades have sought to restrict the deadliest kind — pursuits — hundreds of fatal chases involving police officers are recorded every year across the U.S., and many victims are innocent bystanders, experts said.

According to Chicago Police Department data NBC News obtained through public records requests and first reported, the city has seen a significant amount of wreckage from police pursuits and emergency response crashes.

From August 2017 to the end of last year, the department recorded two dozen fatal chases and 617 crashes during pursuits, the data show.

Fatal pursuits in Chicago far outnumbered those reported during the same period in the country’s two largest cities — six in Los Angeles and two in New York City — according to Fatal Encounters, the independently run database that tracks every deadly interaction with police in the country. (The New York Police Department didn’t respond to a request for confirmation. A Los Angeles Police Department spokesperson referred to the department’s public records unit, which hasn’t yet provided data.)

During the same period, data show, Chicago police recorded 729 emergency response calls that resulted in crashes. Twenty-one civilians and 225 officers were injured.

It’s harder to determine how often officers responding to emergency calls are involved in fatal crashes. No agency tracks nationwide data, said Geoffrey Alpert, a professor of criminal justice at the University of South Carolina. But there are examples of officers’ fatally striking people while responding to these calls.

In New York City in 2020, a patrol car rushing to a call for assistance from another officer drove through a red light, killing a woman crossing the street. And in April, a South Carolina sheriff’s deputy driving to a report of an armed robbery struck a car, killing its 80-year-old driver. (State authorities are investigating the cases, and no officer has been accused of a crime.)

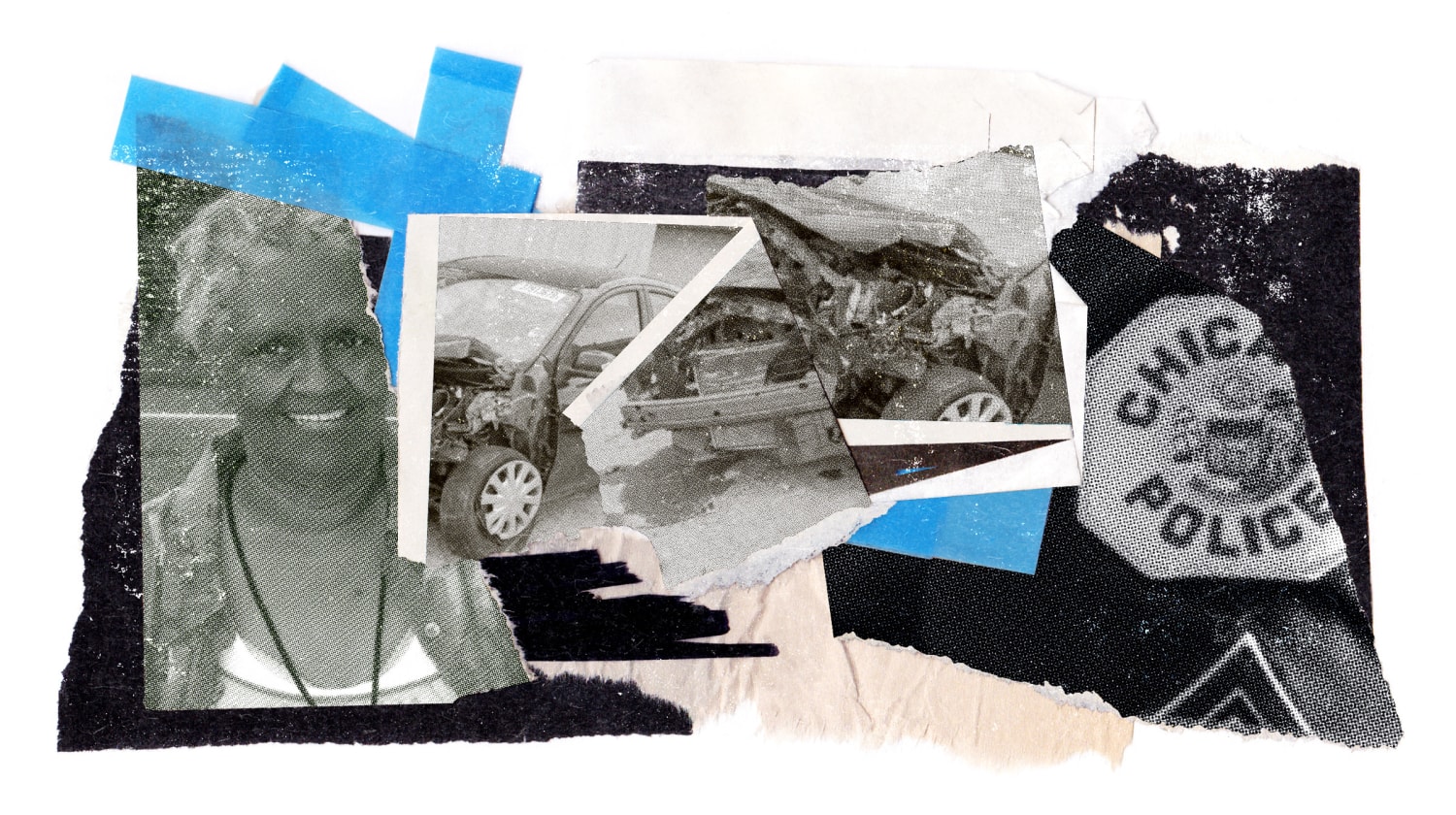

For Dwight Gunn, whose mother was killed in a police collision three years ago in Chicago, the problems underlying these speed-fueled crashes run deep.

“When we hear sirens and lights flashing, we all tend to lean toward the right of that officer to do whatever’s necessary for the sake of whatever issue they’re addressing,” he said. “However, when we put that trust in public servants, there needs to be accountability behind that. And if you don’t have the proper training and the proper oversight, then you find yourself in very dire straits. And that’s where we are. But not until there’s enough tragedy do people begin to pay attention.”

‘Reckless abandon’

A blue Toyota sedan approached an intersection on Chicago’s West Side on May 25, 2019. It was Memorial Day weekend, and the people in the car had left a family cookout to celebrate a college graduation.

They were on their way to drop off the family matriarch, Verona Gunn, when her daughter, who was driving, paused. Three police cruisers — their lights flashing — slowed at the intersection, then drove through it.

Seconds later, two fast-moving police vehicles responding to a report of a man with a gun barreled into each other at the intersection — a violent crash that vaulted one of them into the blue sedan, according to security camera video provided to NBC News by a lawyer for Gunn’s family.

Gunn’s daughter and her boyfriend were injured. Gunn, 84, a retired schoolteacher described by her son as honest and true, died a few hours later. She’d suffered internal trauma, Dwight Gunn said.

Ten officers were also injured, according to a crash report.

Three years later, the Gunn family is still searching for justice in an incident her son said “never should have happened.” Dwight Gunn, the senior pastor of a West Side church, pointed to emergency services audio obtained by his lawyer and shared with NBC News that recorded officers moments before the crash saying the gun had been recovered and dispatchers repeatedly telling responding officers to “slow down.”

“They’re moving through a highly populated community with reckless abandon, totally ignoring the directives given by dispatch,” said Dwight Gunn, 51.

A police department spokesman declined to discuss the allegations or provide details about the crash, citing a pending wrongful death lawsuit the Gunn family filed in 2019. The city’s law department didn’t respond to requests for comment. There was no response to messages left at phone numbers listed for the two officers who crashed into each other.

The police department’s civilian review board completed an investigation into the incident last year. The findings, which aren’t binding and haven’t been made public, are with the law department, a review board spokeswoman said.

It’s difficult to tell how many emergency calls involving Chicago police have been deadly.

Crash data obtained by NBC News appear incomplete: The column for fatalities didn’t list any, including Gunn’s death, and the data indicate only two officers were injured in the crash. The department didn’t respond to a request for comment about the apparent discrepancy.

‘Not enough time, not enough money’

In 2015, a team of academic researchers studying crash data from eight California police departments found that among the 425 officers surveyed, about one-third reported having been in on-duty collisions in the past three years, and 53 had been in two or more.

Experts attribute the high rate of crashes to factors including speed, fatigue, poor training and extended lengths of time behind the wheel.

Hope Tiesman, a research epidemiologist at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, also pointed to distractions in police cruisers.

“Patrol cars are becoming similar to cockpits in fighter jets in regard to the number of technologies and in-car electronics,” she said. “Humans do not multitask well, though we think we do.”

Car crashes were a leading cause of death for officers over the last decade, with an average of 31 killed every year, according to the National Law Enforcement Memorial Fund. Only gun killings and job-related health problems accounted for more.

Researchers are still trying to understand what measures effectively blunt the dangers of emergency driving.

A combination of tactics used by police in Las Vegas after a string of fatal collisions more than a decade ago helped patrol crashes fall by one-fifth and injuries dip by almost half from 2011 to 2013, according to a 2019 evaluation published in the American Journal of Industrial Medicine.

Among the new practices were limits on speed — officers couldn’t go 20 mph over the limit with lights and sirens on — and a marketing campaign featuring sobering videos with relatives of people killed in crashes, said one of the study’s co-authors, Jeffrey Rojek, an associate professor of criminal justice at Michigan State University.

The problem, Rojek said, is it isn’t clear which tactic worked best. And it may be harder to persuade less ambitious or well-funded departments to focus more on safe driving, especially in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, when many remain under pressure to sharpen their de-escalation and use-of-force policies.

“In the ideal world, they should be having more driver training,” he said. “There’s not enough time, not enough money.”

‘Chase until the wheels fall off’

Pursuits are the most dangerous kind of emergency driving an officer can do, Alpert said.

For decades in the 1900s, departments largely embraced pursuits and officers operated under a philosophy of “chase until the wheels fall off,” Alpert said. “It was more important to catch the bad guy than it was for officer and/or public safety.”

By the ’80s and the ’90s, departments were adopting stricter rules, such as “the balancing test” — a risk analysis that weighs the need to apprehend against the danger to public safety. Alpert advocated for an even stricter policy, which some departments implemented, that limited chases to violent crimes.

But even as more departments began adopting such policies, the number of fatal pursuits remained relatively stable. From 2006 to 2019, there was an average of 326 deadly chases annually, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. In 2020, the most recent year for which data are available, there were 455.

Roughly a third of the crashes involve innocent bystanders, Alpert said.

Experts aren’t sure why the additional restrictions haven’t led to fewer fatal pursuits.

Nichole Morris, a mechanical engineer at the University of Minnesota who’s leading a research effort examining pursuits across the state, described many of the new restrictions as “legalese written by lawyers” that are likely difficult for officers to follow. She isn’t optimistic that restrictive policies will result in fewer pursuits.

A dangerous practice

In Chicago, even when a chase wasn’t fatal it often ended badly, according to the police department public records data. During the nearly 3½ years included in the data, just over half of the department’s 1,197 pursuits resulted in collisions. Civilian injuries were reported in just over one-third of those crashes.

The police spokesman didn’t respond to questions about the figures. He provided a copy of the department’s vehicle pursuit policy, which noted the high number of crashes locally and described chases as “inherently very dangerous.”

The agency’s goal, the document said, is to have officers “consider the need for immediate apprehension of a fleeing suspect and the requirement to protect the public from the danger created by eluding offenders.”

The top official in Chicago’s police union didn’t respond to requests for comment.

It isn’t clear what alleged crimes have prompted so many pursuits in Chicago. In Minnesota, a survey of 29 public defenders and people who fled from police found that drug and alcohol use, probation violations and canceled driver’s licenses were factors in decisions to flee.

Nine officers cited traffic violations that revealed cars with stolen plates as a top reason for initiating pursuits, said Samuel Jacobs, a researcher working with Morris who conducted the survey.

Revised chase policy

In June 2020, a Chicago officer chasing a suspect driving a vehicle possibly linked to a string of suburban crimes crashed into an oncoming SUV, killing the driver, Guadalupe Francisco-Martinez, 37.

In a letter to Mayor Lori Lightfoot and other officials, Dwight Gunn called on the police department to adopt the “Verona E. Gunn Safe Driving Protocols.”

He asked the city to require enhanced mandatory training, annual driving certification and other measures to help avoid “this unimaginable pain of a loved one taken because of an officer’s disregard of vehicle operation safety.”

Gunn’s lawyer said he hadn’t heard back from Lightfoot’s office or the police department. The police spokesman and the mayor’s office didn’t respond to requests for comment about the letter.

After Francisco-Martinez’s death, Lightfoot said she had been “very concerned” about pursuits. The department revised its chase policy shortly afterward.

The revisions, which went into effect Aug. 15, 2020, limited the role of unmarked cars in chases and banned pursuits for traffic offenses and property crimes. It also clarified that officers need to check for approaching traffic at intersections.

Alpert, the pursuit expert, reviewed the updated policy for NBC News and said it appeared to have holes: It doesn’t define how officers should approach cars suspected of being stolen, for instance, and it allows police to chase people believed to be driving under the influence.

“The only thing worse than a drunk driver is a drunk driver being chased by the police,” he said.

Still, Alpert said, the new restrictions could, in time, reduce the number of chases.

According to the public records request data, the number of pursuits in Chicago in 2021 — 317 — outpaced the number of chases from each of the previous three years.

During the same period, the number of crashes from pursuits rose slightly over the year before, to 127, as did the number that included civilian injuries, with 38.

Four people were killed in pursuits last year, the same as 2018.

Alpert said he didn’t make much of the jump, noting the number of pursuits and crashes has changed only “marginally” and saying more time is needed to properly assess the new policy.

The police spokesman didn’t respond to requests for comment on the data or Alpert’s analysis.

From Dwight Gunn’s vantage at Heritage International Christian Church on West North Avenue, little seems to have changed with what he sees as the police department’s “cowboy mentality.”

“At any given time, police are flying up and down the street,” he said. “I cringe daily because of all the activity I see. I’m always wondering who’s the next Verona Gunn.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com