Generally speaking, Fabisiak said, “It’s cheaper for industry to pay the penalty, pay the fine, to be allowed to continue to pollute.”

A Shell spokesperson said, “We’ve worked closely with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PaDEP) to fix the issues that led to prior violations, and Shell Polymers Monaca (SPM) is resuming production as a result. We’ve learned from previous issues and remain committed to protecting people and the environment, as well as being a responsible neighbor.”

“At first I was happy they’re being held accountable,” said Flint, who lives in Enon Valley, Pa. “But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that this is just putting a price on our lives.”

A burn pit

To date, Shell has submitted 43 malfunction reports to DEP. And since the plant became fully operational in November, state records show the agency has dealt 11 “notices of violation” to the company, nearly all due to excess emissions.

Local environmental activists and residents have been sounding the alarm for months, and for some, the civil penalty is a complicated victory. “I think it is really the bare minimum,” said Anais Peterson, 25, an organizer with Eyes on Shell, a local, citizen-led advocacy group that has been pushing for more transparency about, and regulation of, the plant’s emissions.

“How much wiggle room are we giving them?” Peterson said. “If Shell has said, ‘We can’t operate in compliance,’ the DEP should say, ‘Then you’re not operating.’”

In Beaver County, forested hills frame towns tightly packed along the banks of the Ohio River and its tributaries. At night, an eerie, sometimes orange glow from the Shell cracker beams through the sky, visible for miles.

In February and March, two separate, dramatic flaring events occurred as residents were already struggling to cope with a train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio — just a half-hour away — that ignited a toxic inferno. Plumes of black smoke and orange fire billowed from the cracker’s stacks for hours.

“I feel like we’re kind of next to a burn pit,” said Rachel Eshom, a 38-year-old registered nurse who lives roughly two miles from the Shell plant.

Residents of the Ohio River Valley, which includes swaths of Ohio and southwest Pennsylvania, are no strangers to pollutive industry and catastrophic environmental events. Before the train derailment, a chemical fire in 2019 forced residents to shelter in place, and a natural gas pipeline explosion in 2018 destroyed one home and prompted evacuation of 25 others.

Eshom said she and her husband have experienced headaches and a burning sensation in their eyes when driving past the plant. She wants to move farther away but doesn’t know where to go.

“It’s just pollution everywhere,” she said.

Communities that host petrochemical plants in Louisiana and on the Texas Gulf Coast have experienced hazardous levels of air pollution, accidents and industrial waste spills, including spills of the so-called “nurdles,” or tiny plastic pellets, that crackers produce.

In 2022, Shell and one of its contractors were forced to pay a $670,000 civil penalty for spilling industrial waste along Shell’s 97-mile stretch of pipeline, built to supply ethane to the cracker. A Shell spokesperson said the company “cooperated with all relevant local, state, and federal agencies and affected communities to ensure Falcon was constructed in a safe and environmentally responsible manner.”

Over the past decade, state leaders in Ohio, West Virginia and Pennsylvania have pursued the plastics industry as a way to breathe economic life into the region, offering multinational companies more than a billion dollars in tax breaks and other subsidies to draw in plastics manufacturing projects.

Shell said it planned to create just over 600 permanent jobs. Data obtained by the Global Reporting Centre through a public records request shows that 457 full-time employees worked at the plant as of early 2022. Shell said it could not provide updated employment numbers.

Beaver County Commissioner Daniel Camp expressed support for the cracker during its construction and believes it will ultimately benefit the region. But since it turned on, he said he’s heard regularly from residents who are concerned about air quality.

“The one thing that we need to do moving forward is making sure that our state and federal leaders hold them accountable,” Camp said.

“Do I believe $10 million is going to do any damage to Shell as a whole? Absolutely not. It’s a slap on the wrist. But it’s in the right direction.”

The Beaver County Chamber of Commerce declined a request for an interview but said, “We have always believed that the growth of industry through businesses like Shell is vital and important for our county.”

‘You shouldn’t be having all these problems’

Petrochemical plants often conduct controlled burning of flammable gas, called “flaring,” to get rid of unwanted waste or to release pressure in the event of a safety concern or an emergency. But flares can also spew large amounts of methane, benzene and other pollutants into the atmosphere.

Richard Corsi, an environmental engineer and dean of the Engineering College at the University of California Davis, said flaring is a “necessary evil.”

Corsi’s research focus is indoor air pollution, and he has previously done emissions-related research funded by both Shell and BP.

“Flares are kind of this emergency response to, ‘We’ve got a problem, we’ve got to start burning stuff,” he said. “The hope is that you’re not forming lots of bad pollutants, but you always form some pollutants when you combust.”

According to Wednesday’s consent order, the cracker plant had nine flaring violations between June 23, 2022 and April 5, 2023.

Corsi said that the biggest air quality concerns posed by flaring events are the release of particulate matter, VOCs and thermal nitrogen oxide, because nitrogen oxide and VOCs mix to form ozone when exposed to sunlight, which can create increased risk of respiratory issues. According to DEP, Shell simultaneously violated its rolling 12-month limits of both VOCs and nitrogen oxide from December 2022 through April 2023. It also violated its rolling limit for carbon monoxide in February, March and April.

“The engineering that goes into these plants is pretty sophisticated,” he said. “If you do it right, you shouldn’t be having all these problems.”

Jim Zhang, an air pollution and environmental health expert at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment, said that flaring poses a particular risk for valley communities, like those in Beaver County, where air temperature inversions are common. Inversions happen when air is trapped near the earth’s surface, preventing pollutants from dispersing as they normally would.

“It’s like a tent, and they come and put a lid on top of it,” Zhang said.

Burn or emit anything, Zhang added, and high levels of pollution can accumulate.

That’s of particular significance, given southwest Pennsylvania’s existing air pollution burden, said Fabisiak.

The Pittsburgh metropolitan area currently ranks among the worst in the nation for particle pollution, although air quality has improved significantly in the past two decades, according to the American Lung Association.

“In most cases, when those sites get permitted for their air quality plans, cumulative effects are not necessarily taken into account very well. In other words, it’s only that one specific source that gets looked at, and not really in the context of all of the other sources that might be available around it at the time,” said Fabisiak.

‘I had to make sure it was real’

The cracker plant had a series of malfunctions this spring, as residents and activists pressed DEP to step in.

By February, Shell had exceeded various emissions limits for five months in a row. When black smoke was seen spewing from the stacks for several hours later that month, environmental groups asked DEP to temporarily halt operations at the cracker. The agency denied the request, writing that it was not “giving Shell a ‘pass’ for these violations” but that because of “ongoing evaluations and inquiries,” it could not commit to specific enforcement measures at that time.

In March, a dramatic video taken by a resident showed hoses spraying down the side of a flaring smokestack as flames billowed out.

“I had to pull over and make sure it was real,” the resident said in the video. “How much more can they get away with?”

Shell later announced that it was shutting down portions of the plant to conduct repairs, and in a letter to DEP acknowledged that it had found a construction error partly responsible for the incident. The floors of the flaring structure had been built “2-4 inches lower in places” than designed.

After a malfunction released benzene at the cracker’s wastewater storage facility in April, causing a chemical odor to spread over part of Beaver County, Shell held a community meeting with residents to address the recent issues, its first since August 2022.

Bill Watson, the plant’s general manager, said there were “no reported injuries to workers or to the community because of these violations. But that being said, no violation is acceptable.”

In a statement to NBC News before the penalty was announced, a Shell spokesperson declined to comment on pending litigation with environmental groups but said the cracker plant “is a unique asset, as are the complications that have surfaced there as part of startup — all related to the complexities of commissioning brand new systems and equipment that make up one of the largest construction projects in the country. Throughout construction and now in operations, the safety of people and the environment remain our top priorities.”

At that time, DEP had fined Shell twice for emissions-related violations at the cracker plant, in the amounts of $10,000 and $4,313.

A DEP representative said, “While it is not unusual for any new facility to have some technical issues during its start-up phase, operators are required to comply with Pennsylvania’s environmental laws, regulations, and any environmental permits issued to the operator.”

‘That ship is sinking’

As part of an agreement with environmental groups that challenged Shell’s air permit when the plant was still being built, the company installed a network of air monitors around the perimeter of the site, which continuously sample the area for VOCs. Shell is also required by the state to report emissions as part of its air permit.

But Shell’s network of monitors doesn’t allow residents to get real-time information about the concentration of pollutants in the air at any given moment. Days pass before the data is made public.

A number of residents have installed their own monitors at home. “PurpleAir” monitors are low-cost air quality sensors that measure levels of particulate matter and VOCs in real time. The data is sent to a publicly accessible map, viewable by anyone.

So far, 25 monitors have been deployed in the area as part of a campaign led by Mark Dixon, a Pittsburgh-based filmmaker and environmentalist.

“Putting monitors where people are feels like a common-sense practice,” especially in the context of an “unequal relationship” between Shell and nearby residents, Dixon said.

“Our leaders have hitched our economic wagon to this highly polluting, accident-prone industry,” said Dixon. “And we are going to reap the consequences of that unless we push back, keep a close eye on what’s going on, and try to hold them to account as best we can.”

While the monitors are not regulatory grade, in combination with other information – like daily weather forecasts and observations of smells and visible emissions – they can help paint a more complete picture for residents who want to know what’s in the air before going outside.

“What people can do is say, ‘Hey, you know, I should really close the windows, close the doors,’” Zhang said.

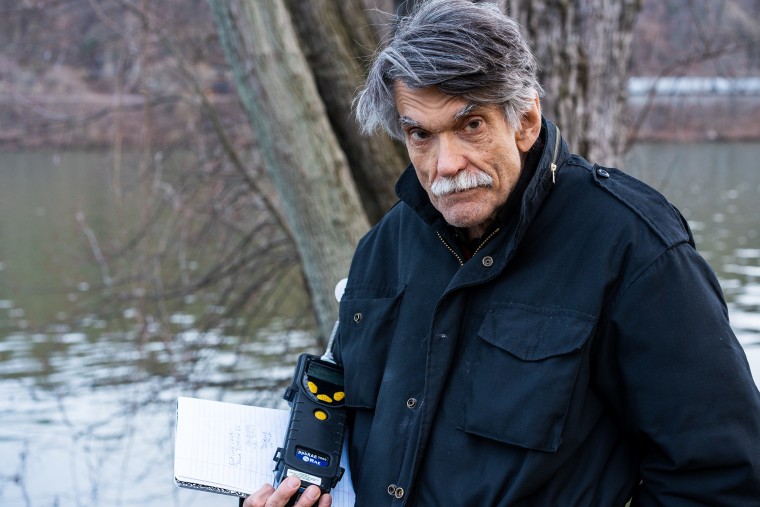

Clifford Lau, a 67-year old chemist and Eyes on Shell volunteer, periodically samples the air around the plant for VOCs. Lau’s monitoring is part of an Eyes on Shell effort — partially funded by the EPA — to independently track air quality.

Lau said that while exceeding permitted pollutant levels is problematic, he is more worried about the public health risks posed by the particular cocktail of chemicals released at a given time. The cracker emits various pollutants consistently as part of its regular operations, including carcinogens like benzene and 1-3 butadiene.

“What effect does that mixture have on the public?” Lau said. “They become guinea pigs, in essence, to find out.”

Lau said he’s concerned that the region risks turning into “Cancer Valley,” a reference to southern Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley,” an 85-mile corridor of petrochemical plants along the Mississippi River where the EPA has said residents suffer from high rates of cancer and other adverse health effects linked to pollution.

“What these people are being exposed to here is a low level, but 24/7, 365,” he said.

As Eyes on Shell watchdogs continue to test the air quality, hold community meetings and report potential permit violations, some residents contemplate if they can keep living in the plumes of the Shell cracker.

Sharon Kessler, 66, who lives on a hill roughly four miles from the plant, worries for her grandchildren’s future and what could happen if they stay in the area.

“Living next to that it’s like being on the Titanic, and you’re locked on the bottom deck,” Kessler said, as she pointed in the direction of the cracker. “That ship is sinking.”

The Global Reporting Centre is an independent and not-for-profit newsroom focused on collaborative approaches to global journalism. The GRC’s work on this article was supported with funding from the Park Foundation and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Andrea Crossan and Britney Dennison of the GRC provided editorial support.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com