SAN ANTONIO — In five performances, a Latino theater company’s restaging of a play about historic but overlooked Mexican American student walkouts rekindled sorrow and pride among audiences, while triggering worries about the present.

The play “Crystal City 1969,” first staged in 2009 in Dallas, was performed for the first time in San Antonio last weekend at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center.

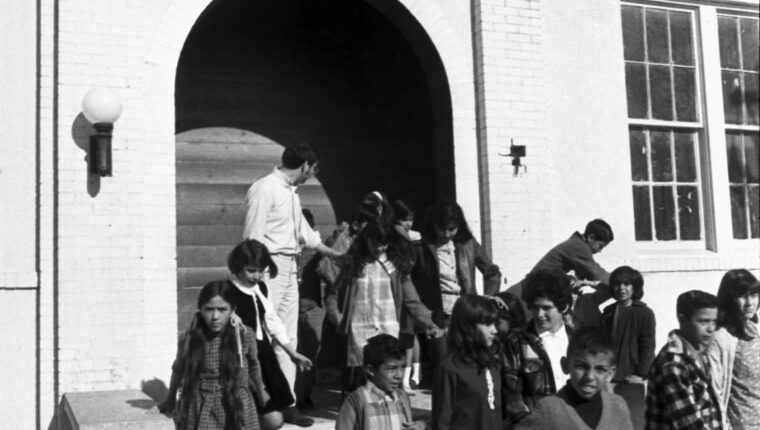

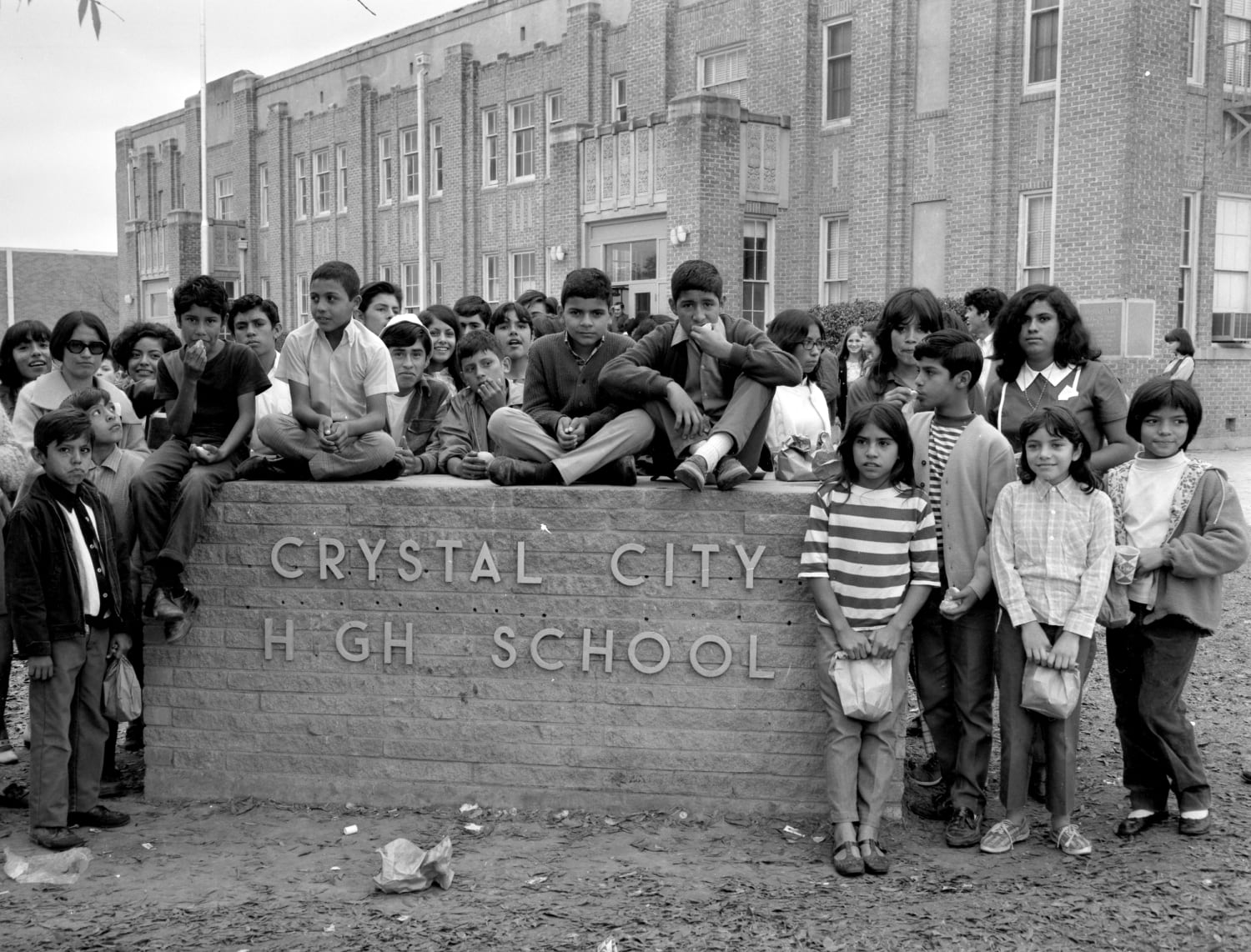

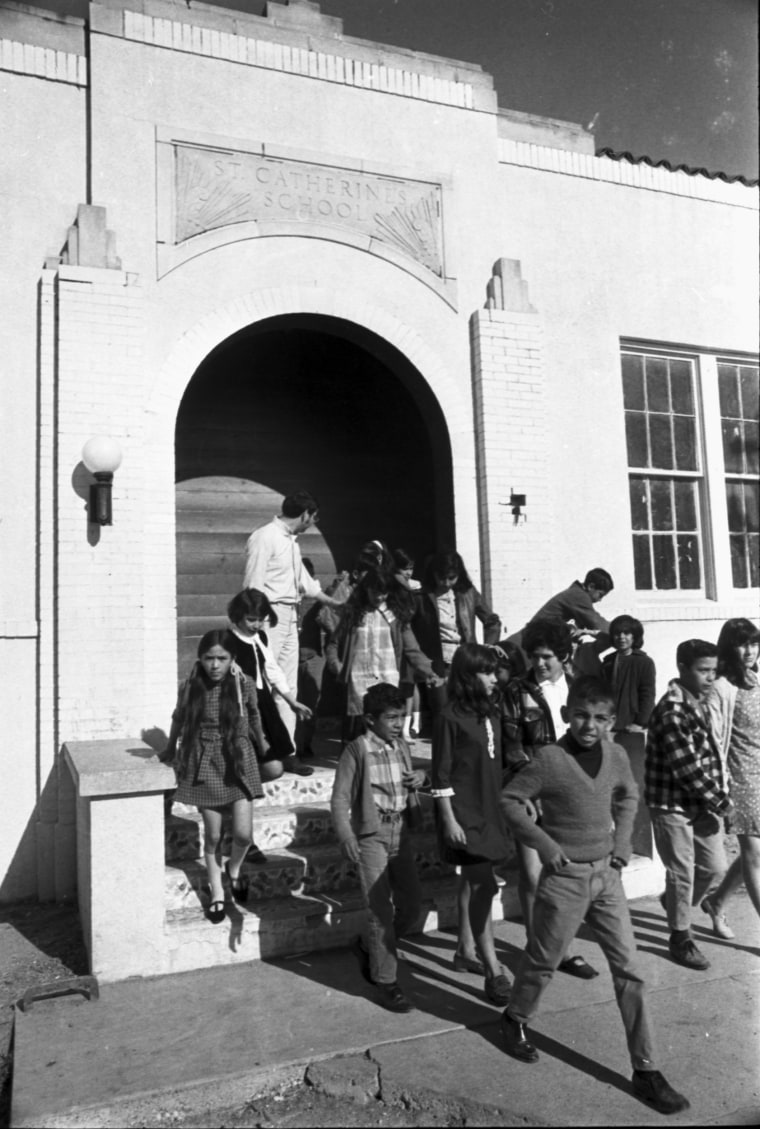

The play tells the story of the Crystal City, Texas, student school walkouts and boycotts, when thousands of students demanded changes from school and local leaders, who were white, and an end to racist and discriminatory treatment of Mexican American students.

“We’d get paddled if we spoke Spanish in class. Discipline was very unequal. We didn’t have Chicano counselors. They demeaned us. They were very racist with us,” Severita Lara told NBC News in 2019.

The students went to the school board with 13 demands, including more Mexican American faculty, the inclusion of Mexican American history in the curriculum, a fair discipline system and more cheerleading slots for Mexican Americans — since the faculty had put limits on how many Mexican Americans could be on the team.

They also demanded educational equity. Lara said she wasn’t allowed to take a chemistry class because she was told that was only for students who were going on to college. She did go — and earned a degree in biology with a minor in chemistry.

The play captures some of that, how women and mothers became the catalyst for parents to organize and how their actions were part of the formation of the Raza Unida Party by one of the walkout organizers, José Angel Gutiérrez.

“When we were active, there were no books. There were no mentors. There was nobody to tell us how to do what we had to do. There was just rage,” said Gutiérrez, who went on to become an attorney and is a professor at the University of Texas at Arlington.

Students in San Antonio and other communities in South Texas had also staged walkouts in the late 1960s and early ‘70s.

Some members of the audience had experienced what took place in the play, having their own memories of being hit in school by teachers and principals for speaking Spanish and having been denied educational opportunities.

But the events depicted in the play, new to some, serve as a reminder of what is at stake now, as conservative elected leaders and school boards ban ethnic studies books and those with LGBTQ characters and themes and put limits on the teaching of Black, Latino and other history, according to David Lozano, who co-wrote the play with Raul Treviño.

“This is our story and it’s also a history that we’ve been denied growing up in schools and even in college. You can have a master’s degree and still not know the story of Crystal City,” said Lozano, who is the executive artistic director of Cara Mía Theatre in Dallas.

“As long as this story is being denied in our schools, this story is still relevant, and this is 53 years after the first day of the (Crystal City) walkout,” Lozano said.

The showings in San Antonio were the first opportunity for some of the former students who had participated in the walkouts to see the play and gave current Crystal City students and residents the chance to see it. Crystal City is about two hours from San Antonio, but the play has never been staged there.

The attendance for the play in Austin and San Antonio “tells me that Latinos love our history. We are hungry. We are starved for our history and we are still not getting it,” said Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez, director of the University of Texas at Austin’s Center for Mexican American Studies, or CMAS.

“The other thing is, I think there is some unfinished business. I think you can see it when you look at political representation … trying to get people to understand that this community belongs to them and they need to make that claim,” she said, “to make sure our elected officials are really protecting their best interests.”

Rivas-Rodriguez said that at every performance, someone raised the issue of the current movements against teaching about race, racism and identity, such as the recent block by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ administration of a new Advance Placement course on African American studies.

“The people see … that if we want to have our history taught in school and our history woven into the larger American stories and Texas stories, we need to stand up and be counted and then make sure they are included, and if there are attempts to not include them, we need to let our elected officials know,” she said.

It’s a history that is painful for those who lived it. Rivas-Rodriguez said she heard her sister, who sat next to her in a performance Saturday, sniffling through the play “because we recognized these are some of the things that happened to us in our childhoods.”

Rivas-Rodriguez grew up in Devine, Texas. When her mother, who she said spoke “perfect unaccented English and perfect unaccented Spanish,” took her to enroll in first grade, the superintendent attempted to enroll Rivas-Rodriguez in a class for children with learning disabilities.

“My mother asked why and he said, ‘Well she doesn’t speak English, does she?'” Rivas-Rodriguez said. He then asked Rivas-Rodriguez if she spoke English.

“That was one of the many ways they managed to segregate kids, to make them feel different,” Rivas-Rodriguez said.

James Garcia, a Phoenix playwright and journalist who hosts a Latino-focused radio show, “Vanguardia America,” experienced similar discrimination while growing up on Chicago’s South Side. Growing up in a Mexican American household, he spoke no English. On his first day of school, he couldn’t tell the teacher he needed to go to the bathroom.

“The next thing I knew, I was on the front steps of the school and was told, ‘Wait here until your mother comes and gets you,'” he said. “I learned later they told her don’t bring him back until he learns English.”

“People forget there was a kind of cultural trauma that affected Mexicans and Mexican Americans,” Garcia said. The effect of that sort of discrimination was to tell Mexican American and Mexican students that their language, their culture, was worthless, valueless and something to be ashamed of, Garcia said.

Plays like “Crystal City 1969” and “Voices of Valor,” a play Garcia has staged about Latinos who fought for the country, help dismantle the Hollywood depictions of Mexicans as bad guys, thieves and ignorant, Garcia said.

Staging of the play in San Antonio was part of the 50th anniversary celebration of UT CMAS, which occurred during the pandemic and therefore had delayed some of its events. It was also staged last year in Dallas and outdoors in Austin to an enthusiastic crowd of about 600, according to Lozano, along with some who watched it online.

Olga Muñoz Rodriquez was a 26-year-old mother who helped students in Uvalde, Texas, organize walkouts in 1970, after the school board decided not to renew a contract for a teacher, George Garza, the only Spanish-speaking teacher in the school, Robb Elementary.

This is the same school where 19 students and two teachers were killed by a gunman last year.

Rodriquez attended one of the performances of “Crystal City 1969” over the weekend. “I kept wanting to say, ‘That happened in Uvalde!'” said Rodriquez, 78, who went on to write and publish her own newspaper and a book on the heroes of Uvalde. “They inspired the kids in Uvalde. They inspired us all.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com