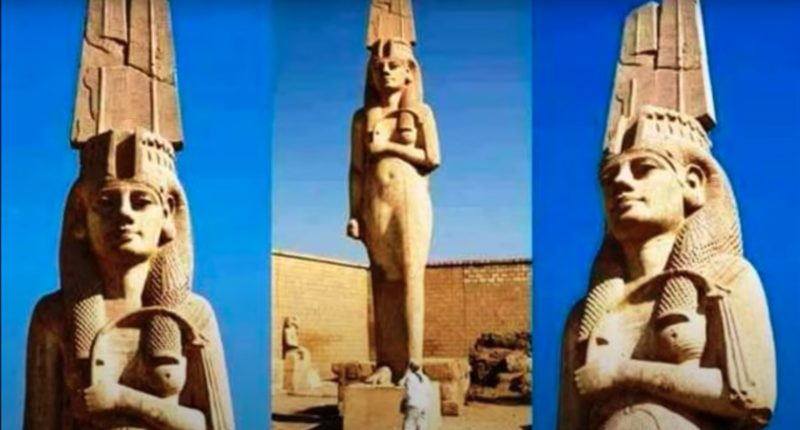

RESEARCHERS have unearthed the final resting place of a powerful queen who might’ve been ancient Egypt’s first female ruler.

A recent unearthing of ancient wine in Upper Egypt has offered archaeologists clues about a powerful ruler from 5,000 years ago.

The discovery of hundreds of wine jars was made about 10 km from the Nile River by archaeologists from the University of Vienna.

Specifically, the wine was found in the tomb of Meret-Neith, otherwise known as Egypt’s forgotten female “king.”

The fact the female ruler was buried with such a large amount of wine now tells researchers that she held great wealth and importance at the time.

In fact, some experts believe that Meret-Neith might have even been the first female ruler of ancient Egypt.

This theory is only furthered by the lavishness of Meret-Neith’s resting place, which includes the tombs of 41 courtiers and servants.

Some researchers believe she may have achieved her position of power by serving as Queen regent for her young son.

Archaeologists also found her name scribbled under a list of kings at her son’s tomb at Saqqara.

“The very fact of having added her name to the list of kings shows that something highly important had to have happened with Meret-Neith,” Ronald Leprohon, a professor emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Toronto, told Live Science.

Most read in News Tech

“No other queen in the early dynastic period possessed so many royal privileges,” Jean-Pierre Patznick, an Egyptologist at Sorbonne University in France, added.

Researchers unearthed inscriptions that stated Meret-Neith was responsible for important offices like the royal treasury.

“Queen Meret-Neith was probably the most powerful woman of her time,” University of Vienna archaeologist Christiana Köhler said.

“Today’s researchers speculate that she may have been the first female pharaoh in ancient Egypt and thus the predecessor of the later Queen Hatshepsut from the 18th dynasty,” she added.

“Her true identity remains a mystery.”

The queen’s tomb was first uncovered by British Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie in 1899-1900.

Analysis showed that her monument was not all built at the same time but in intervals.

Other research also suggests that the courtiers and servants were buried with the queen as an honor.