Californians this week are honoring the influential Filipino American labor rights leader Larry Itliong, whose legacy as a father of West Coast labor organizing continues amid recent strikes in the auto, entertainment, hotel and health care industries.

Several celebrations across California — from a solidarity march in Poplar on Saturday to a new exhibit at the Filipino American National History Society Museum in Stockton — are paying tribute to Itliong, who played a major role in founding the United Farm Workers union and orchestrated one of the most influential strikes in the state’s history.

The events coincide with California’s Larry Itliong Day on Oct. 25 — the late activist’s birthday — which was first designated by then-Gov. Jerry Brown in 2015. But as the Filipino American community and others look back on the organizer’s achievements, many say that Itliong’s work remains relevant as ever given a nationwide labor reckoning that has been felt particularly in California.

“He employed strategies and deployed strategies that a lot of people still use today,” said James Zarsadiaz, an associate professor of history at the University of San Francisco and director of its Yuchengco Philippine Studies Program.

Itliong, who was born in the Philippines in 1913 and immigrated to the West Coast when he was 15, rose to prominence among “manongs,” or the early generation of Filipino immigrant men who were often relegated to agricultural labor. While Itliong began his organizing efforts shortly after he arrived in America, participating in walkouts and fighting for fair labor contracts, he was best known for the Delano grape strike of 1965. Itliong, along with fellow labor organizers Philip Vera Cruz, Pete Velasco and Andy Imutan, led thousands of Filipino farmworkers in a strike against Coachella Valley grape growers, demanding a salary of $1.40 an hour and 25 cents per box, up from an average of 90 cents an hour and 10 cents per basket that they had been making.

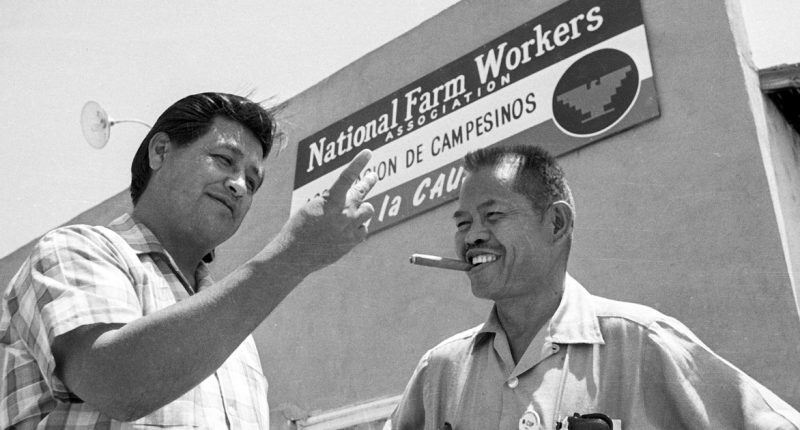

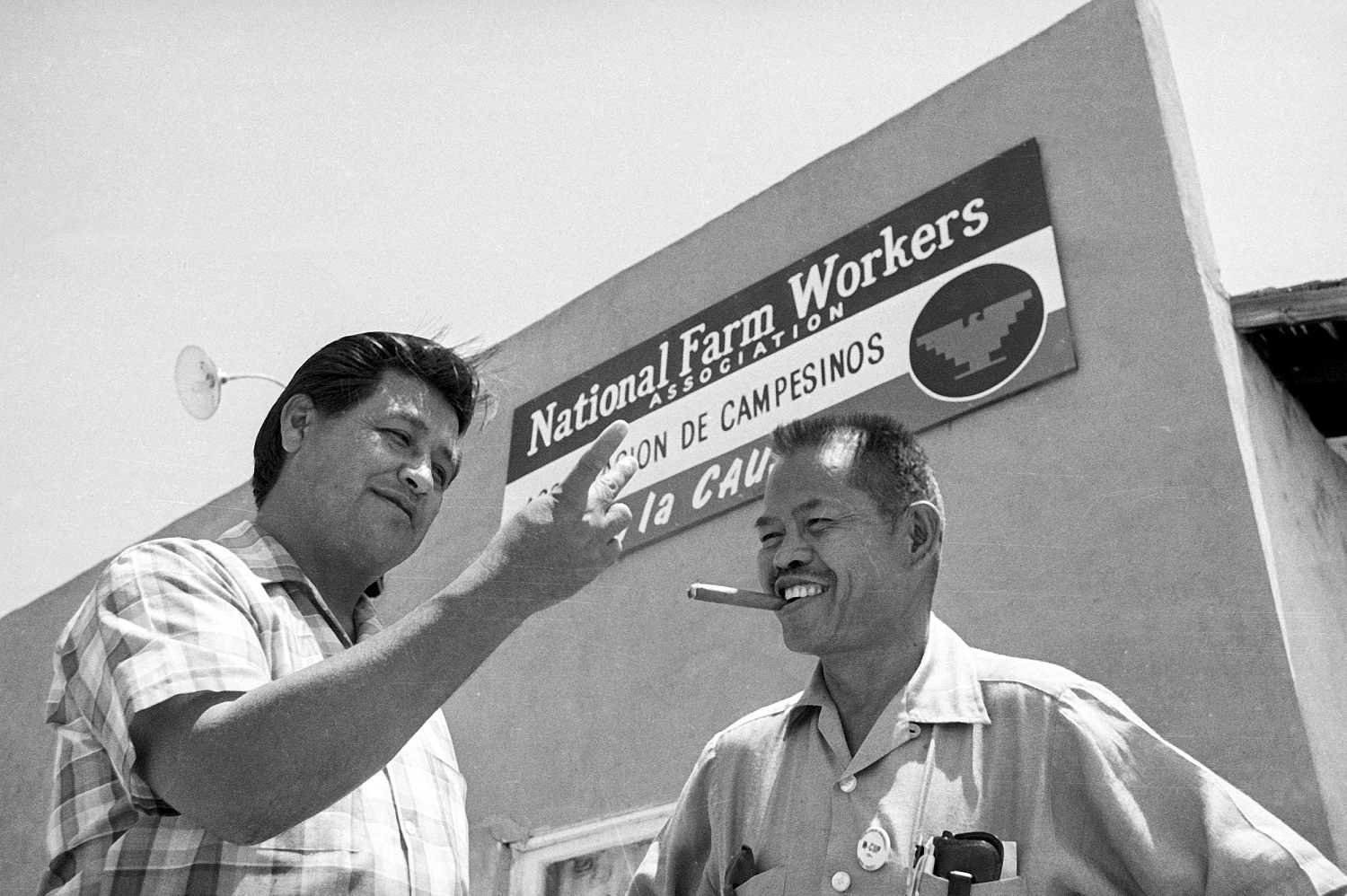

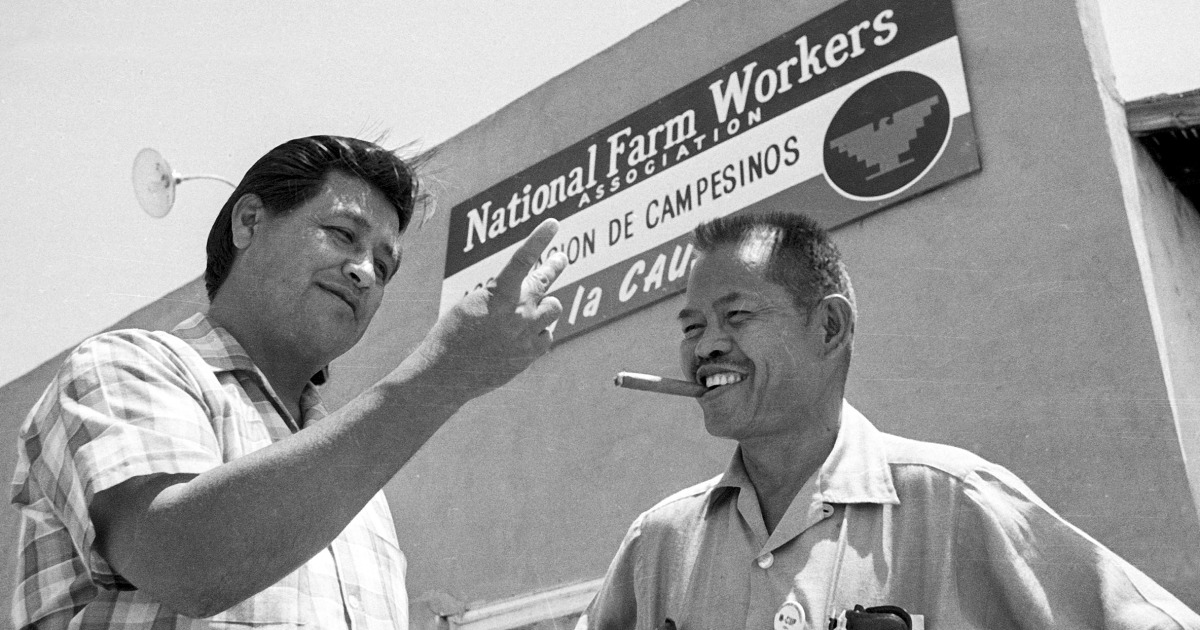

The strike wasn’t initially successful, Zarsadiaz said. The Filipino farmworkers needed the support of Mexican workers, who made up a significant portion of the agricultural labor force, but farm bosses intentionally kept the groups segregated, Zarsadiaz explained. Growers often tried to pit the groups against each other, and differences in language and culture further made organizing across community lines more difficult. But Itliong excelled at coalition building, Zarsadiaz said. He was able to establish a relationship with César Chávez, the Latino civil and labor rights champion, in part because they both spoke English and were seen as charismatic figures in their communities.

With the help of Chávez and fellow labor leader Dolores Huerta, Mexican farmworkers joined the strike, forming a united front and leading to a massive boycott that did not officially end until 1970. The organizing between the two communities also led to the formation of the United Farm Workers union in 1967, with Chávez as director and Itliong as assistant director.

“That legacy endures and is important today, because they really were at the forefront of trying to build multiracial coalitions and to build relationships with fellow workers regardless of race,” Zarsadiaz said. “A lot of it is made possible because people fostered relationships and alliances across lines that were especially rigid back then.”

While Chávez has largely been seen as the face of the farmworker labor movement, the legacy of Itliong, who spent his later years organizing in global labor movements, has not reached similar heights of recognition, Zarsadiaz said.

“Even despite these last few years of greater visibility and representation, Asian Americans are still arguably very invisible or made to be invisible in the public sphere,” Zarsadiaz said. “Larry Itliong is unfortunately one of those people who despite having done a tremendous amount of work in labor rights and the recognition of unions, is given a back seat in the American narrative.”

However, Zarsadiaz added, Itliong made an indelible mark in the labor sphere, and his work challenged stereotypes that continue to plague immigrant groups.

“For a lot of immigrants and refugees, there’s a feeling that one should express gratitude and be grateful and appreciative of the opportunities that are ‘given’ to them in the United States,” he said. “Ultimately, Itliong really felt that he had no choice, and I think a lot of workers then and workers now feel that they have no choice. … For a lot of immigrants, they just felt that there is no other option but to fight for it.”

For more from NBC Asian America, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com