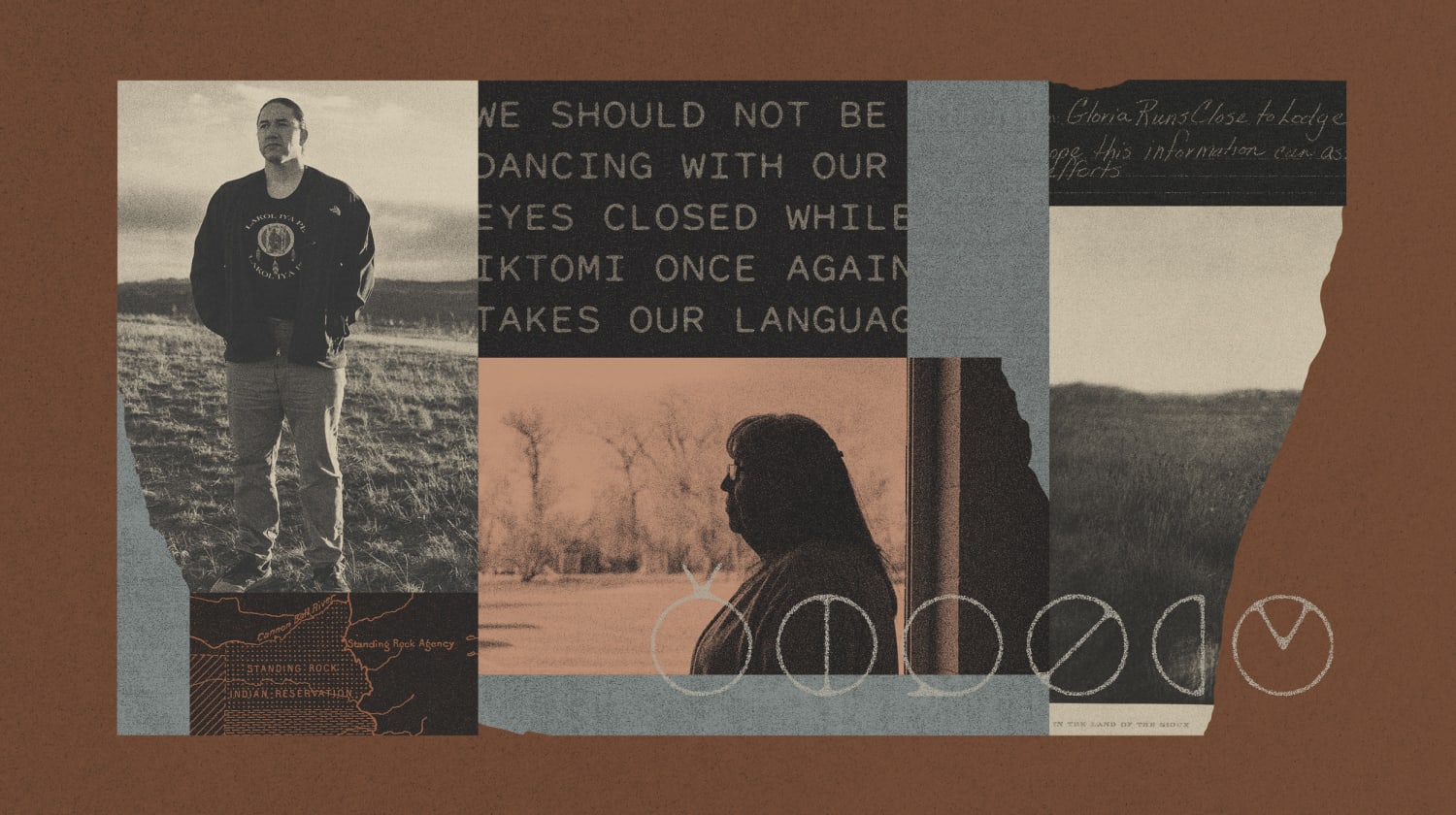

On May 3, the tribal council voted nearly unanimously to banish the Lakota Language Consortium — along with its co-founder Wilhelm Meya and its head linguist, Jan Ullrich — from setting foot on the reservation. What the council took into consideration wasn’t just the organization’s dealings with the Standing Rock Sioux; it turned out at least three other tribes had also raised concerns about Meya, saying he broke agreements over how to use recordings, language materials and historical records, or used them without permission.

Meya denies this. A spokesman shared letters of support for Meya’s work from five tribes and tribal schools, though in recent interviews and statements to NBC News, officials with four of those tribes said they had concerns about Meya’s methods.

Native Americans have been mined for financial benefit and academic accolades for centuries. Information collected on Native Americans has rarely been taken with their consent or been used to serve their communities, whether through research done on Indigenous remains robbed from gravesites or on blood samples used without permission. Still, there are Lakota people who support what the consortium is doing: They say preserving the endangered language is paramount.

This work has been lucrative for Meya, who started the Lakota Language Consortium in Indiana in the early 2000s. He’s also the CEO of The Language Conservancy, a nonprofit organization he founded soon afterward that works to revitalize other Indigenous languages.

In tax filings for 2020, Meya reported an annual salary of about $210,000 from his two nonprofit groups, according to tax disclosure documents. That kind of money bothers some in the Native American communities he’s worked in; on the Standing Rock reservation, the median income is just over $40,000.

Meya’s organizations have received more than $3.5 million in federal grants over the past 15 years for language revitalization projects with tribes across the country, records show. The Department of Health and Human Services alone has paid the Lakota Language Consortium nearly $1 million to create some of the textbooks the organization sells for $40 to $50 apiece.

Meya says his work is a vital tool in preserving the Lakota language, which did not previously have a standardized written form. He estimated that there are fewer than 1,500 fluent Lakota speakers left and that over the last decade and a half, the organization has helped add 50 to 100 more.

“Just because money is involved in it does not inherently make it an evil thing,” Meya said in a recent interview with NBC News. Most of the products his organizations make are free, he said, but the cost of printing textbooks has to come from somewhere. “That tends to be sometimes part of the rhetoric, ‘Oh, there’s money involved. It must be, you know, part of the overall colonization effort.’ Well, you know, that’s just not realistic.”

But several Indigenous academics, legal experts and tribal leaders say the consortium is asserting control over more than the teaching materials it makes; it’s the community-specific information and tribal history that’s contained within the books. Some of the words and phrases in the consortium’s materials have never been recorded or transcribed before, and charging a marginalized community any fee for them is unethical, the experts said.

Taken Alive and a growing number of tribal citizens believe all the dictionaries, textbooks and recordings should be free and accessible to the Indigenous communities that created the languages the products teach.

The conflict is part of a bigger dispute over how to preserve Native American languages and oral histories and whether outsiders should be allowed to make money off of this work.

Estimates vary, but there are slightly more than 100 Native American languages still spoken today, less than half of what existed before European colonization began. Whether through the destructive violence of Manifest Destiny or the assimilation efforts of the Indian boarding school era, the U.S. campaign to eliminate Native American languages has been highly effective. Most of those that remain are in danger of extinction. Many tribes, especially smaller ones with fewer resources, rely on non-Native organizations to preserve their languages.

A common trait of Native American cultures is to hold things like land, resources and knowledge communally. That runs into conflict with U.S. copyright laws, which allow companies and nonprofit organizations to commoditize their work product — including pieces of a shared language.

The Lakota Language Consortium notes on its website that “no one can copyright a language,” and the consortium says it shares its materials with those who ask to make copies for educational purposes. But the copyright on the materials still gives the organization control over how the information is used, which is what some tribal leaders find objectionable.

Even if a tribal nation has intellectual property laws protecting its cultural information, if it lacks the legal staff to assert control over that data, legal experts say it can still be vulnerable.

The debate over how information collected from tribes is handled has caught the attention of tribal citizens across the about half-dozen reservations where Lakota is a first language. The controversy has spilled into tribal politics and social media, igniting a fierce debate over identity, decolonization and tribal sovereignty.

Tribes in this situation are typically at a disadvantage, said Jane Anderson, an associate professor of anthropology and a legal scholar at New York University. Not only do tribes rarely share in the profits of language preservation efforts, they often have to pay part of the costs to implement them and have to purchase the end product, she said.

“There is something deeply unethical and inequitable in relation to that, and I hear it all the time across Indian Country,” she said.

Makalika Naholowa’a, a Native Hawaiian attorney and the executive director at the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, said when organizations that trade in Indigenous data don’t freely share that information with the communities they gather it from, they are akin to miners or loggers, taking a valuable resource and selling it to whoever wants it.

“Data is the new oil,” she said.

Words passed down for generations

Ray Taken Alive started learning Lakota as a kid by listening to his grandmother Delores Taken Alive, who was a first-language speaker. She grew up in South Dakota, where her family had lived since long before their land was part of the United States. Delores was proud to have been given her Lakota name, Hiŋháŋ Sná Wiŋ, or Rattling Owl Woman, by her great-grandmother, who survived the massacre at Wounded Knee.

As a child, when Delores was drifting off to sleep, she listened to her parents and grandparents tell stories in Lakota, and that’s how she learned the history of her people.

With the number of Lakota first-language speakers dwindling, Delores was eager to help preserve and transmit the language. Beginning in 2005, she recorded words and stories for Jan Ullrich, the linguist, and reviewed new entries in the Lakota Language Consortium’s dictionary. She signed an agreement with the consortium that paid elders up to $50 per hour, in exchange for exclusive rights to publish what they shared.

Meya said he considered Delores a friend and that she contributed important work to the dictionary. “She’s always wanted her stuff out there so much,” he said. “That’s been her kind of cause.”

Ray Taken Alive began formally learning Lakota in elementary school. He continued with classes in college and eventually used the curriculum his grandmother helped create, gradually piecing together his people’s words. Over time, those words did what they’ve been doing since the beginning: They pieced him together, too, he said. They gave him a way of seeing his place in the world that only his ancestors could provide.

After his grandmother died from Covid in 2020 at age 86, Taken Alive said he asked the consortium for her recordings. That’s when he learned the organization retained the “unrestricted permission to copyright” and publish them, according to the agreement she signed.

While the consortium eventually gave Taken Alive copies of his grandmother’s tapes, he said that was the moment he was awoken to something bigger: the extent of the consortium’s control over decades of information collected from the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. His tribe had helped fund the consortium’s effort and supported grants for it, according to tribal leaders, so he believed the Lakota people should have access to what came from it.

Taken Alive decided to start testing the limits of the copyrights. Last year he posted some of the consortium’s lessons in an online language-learning app. The data belongs to the tribe, he figured, and if the organization’s stated purpose is to teach the language, then it should be readily available to Lakota people. But he said soon after posting, he received a copyright infringement notice from the consortium, and the app removed the lessons.

“So I’m supposed to ask the Lakota Language Consortium if I can use my own Lakota language,” Taken Alive asked in one of many TikTok posts that would come to define his social media presence.

A representative for the Lakota Language Consortium said in a statement that the group “has always encouraged teachers to copy and share our Lakota language learning materials with their students. This is clearly different than someone copying the entirety of an author’s work and distributing it as their own.”

Meya told the tribal council in April that the consortium had been working since 2018 to return all the language data it had collected. “That’s been our No. 1 interest for many years, as well as making sure that young people have as much access as possible to these materials,” he said.

But the tribal council grew tired of waiting. This spring it hired an attorney to ensure recordings and writings from hundreds of Lakota speakers are returned.

The entrepreneur and the linguist

Meya was born in Vienna, grew up in Connecticut and moved to South Dakota to attend the Oglala Lakota College in the mid-1990s. That’s when he became interested in Lakota language and history and began learning from tribal elders. But “it was difficult for anyone to learn the language,” he said, “just because there were no materials and nothing very consistent there.”

Meya continued studying Lakota history in graduate school, and eventually he decided to start creating textbooks and lesson plans. He co-founded the Lakota Language Consortium while studying for his doctorate at Indiana University. Today, the consortium and Meya’s other nonprofit organization, The Language Conservancy, work with dozens of tribal nations, including in Australia.

Meya began working with Ullrich, who is now the head linguist at the Lakota Language Consortium, in 2002.

Ullrich grew up in the Czech Republic, and in the 1980s he joined a group of white hobbyists who appropriated Indigenous culture by dressing up as Native Americans, living in tipis and smoking peace pipes, which was captured in a 1995 documentary. After spending several years studying Lakota, Ullrich first visited the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in 1992. He has spent his summers in the Dakotas working on a new Lakota dictionary and teaching since.

“In my capacity as a linguist, I’ve been doing my best to support the efforts,” he said via email.

Most people who have worked with Ullrich, both Native and non-Native, describe him as a capable teacher who is genuinely interested in revitalizing the language. But others have raised concerns about his past hobbyism and disagree with the way the consortium has standardized Lakota, making it easier to translate into languages like Czech and sell in translated texts, which he has done.

Meya and Ullrich, as well as their supporters in tribal communities, describe Taken Alive’s efforts to stop them as an orchestrated disinformation campaign.

“Our track record speaks for itself,” Meya said. “And it’s beautiful, and amazing, and fantastic, and miraculous in every way. And, you know, if there’s people that want to tear it down for their own personal, you know, agendas or whatever, that’s unfortunate.”

Most of the Lakota Language Consortium’s board members are Lakota, and a few of them came to April’s tribal council meeting to defend the consortium’s work as a vital tool for language preservation.

“I speak traditional Lakota, and I gave everything I had to this effort,” said Ben Black Bear, the consortium’s vice chairman and a citizen of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe. “I don’t care if they give me any copyrights or make money on me. I don’t care. The objective is to get the language out there.”

Long battle for sovereignty

Over the past two years, as Taken Alive began speaking out about Meya and Ullrich on social media, he connected with citizens and leaders of other tribes who raised similar concerns about the pair’s practices.

Last year, after Taken Alive confronted Meya at a conference run by the National Indian Education Association, the association asked The Language Conservancy to stop attending its conferences. Diana Cournoyer, the association’s executive director and a citizen of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, said she heard from several members of the association who voiced concerns about the conservancy either not sharing revenues with the communities that created the languages or not fully explaining the extent of its control over the material it collects.

Meya said the tribal citizens who worked with his nonprofits were glad to help with language preservation and understood how their words would be used. “They would seek out to be recorded,” he said.

The situation should start a larger conversation about Indigenous data sovereignty, the ability of tribal nations to control their own information, Cournoyer said. “It’s time to have an open dialogue that results in a solution,” she said.

Naholowa’a, the Native Hawaiian attorney, said Indigenous people’s demands to own their language and culture “are rooted in their human rights.”

She said federal law doesn’t account for the way tribal nations communally preserve cultural and intellectual property or the often inequitable circumstances in which that information is taken.

Most intellectual property attorneys have no understanding of the cultural implications at play, Naholowa’a said, putting tribes at the disadvantage of having to remain vigilant in protecting their citizens’ data. Of the tens of thousands of intellectual property attorneys in the country, she’s found only 14 who identify as Indigenous.

Anderson, the New York University legal expert, said that just because the conservancy is operating legally does not mean its work is ethical.

“You make it free for the communities whose language it is — I mean, that’s just basic ethics and responsibility,” she said.

While some tribal governments have been proactive by creating their own intellectual property laws or hiring attorneys to protect their information, many more have learned the limitations of property law the hard way.

The Pueblo of Acoma have been living on a mesa of golden stucco homes in central New Mexico for over 2,000 years, one of the longest continually inhabited villages on the continent.

While the Pueblo’s language, Keres, has been in use for thousands of years, like Lakota it was never put into a standardized written form. The Language Conservancy began working with the Pueblo to develop a dictionary and curriculum for teaching Keres in 2017.

But the Pueblo terminated its contract with the organization in 2019.

According to a statement from tribal Gov. Randall Vicente’s office, the conservancy’s employees then tried to abscond with the data they had collected, as well as language materials developed by the tribe. In the statement, the office said employees of the conservancy loaded the materials into their cars, and tribal police were dispatched to pull them over and make them return the items.

“Despite these incidents, Acoma still was forced to negotiate with The Language Conservancy for the return of all its property,” the governor’s office said in the statement. It took more than a year for the organization to return everything, the office said.

The tribe’s contract with the conservancy gave the nation rights over any intellectual property created. In 2020, the Pueblo of Acoma and The Language Conservancy signed a settlement saying that the conservancy could no longer teach Keres classes, according to the tribe.

Meya called the criticisms “inflammatory” and “untrue.” He said his work with the tribe halted after new tribal leaders abandoned the project. “The Acoma story is very complex, mostly has to do with the change of leadership at the tribe,” he said.

Sacred stories

For Standing Rock Sioux Councilman Charles Walker, the moment that sealed the Lakota Language Consortium’s banishment was when he learned of the Calico Winter Count.

A lot of the information we have today on tribal nations — their relations with each other, changes in leadership and unique traditions — comes directly from Indigenous people themselves. Many bands of Plains tribes, like the Lakota, kept what are known as winter counts, pictorial histories drawn onto animal hides. Each one is a calendar stretched across the soft underside of a hide, every image capturing the most important event of that year, from first snow to first snow.

Gloria Runs Close To Lodge-Goggles said it was a great honor when she was chosen to keep the Calico Winter Count and its translations. Her ancestor Black Shield documented a multitude of events, including when he acted as Lakota Chief Red Cloud’s interpreter during a diplomatic visit to Washington, D.C., in 1870.

Goggles stored the audio and written translations at the Oglala Lakota College for safekeeping, only to be accessed by students with the family’s permission.

Meya got access to them while attending the college in the 1990s — without Goggles’ knowledge, she said — and he soon began writing and lecturing on their contents. Meya said he received them with the permission of the college’s archivist.

In 1998, Goggles obtained a cease-and-desist order from the Oglala Lakota Tribal Court requiring Meya to return all the materials and copies and to stop publishing or making presentations about the count. But Meya used the information in his 1999 master’s thesis at the University of Arizona, in which he described the Calico Winter Count as “a crucial type of indigenous data set” and “highly credible historical sources that can play central roles in the construction of tribal histories.” Meya later donated copies of the winter count translations to the University of Washington as source material to receive a grant.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com