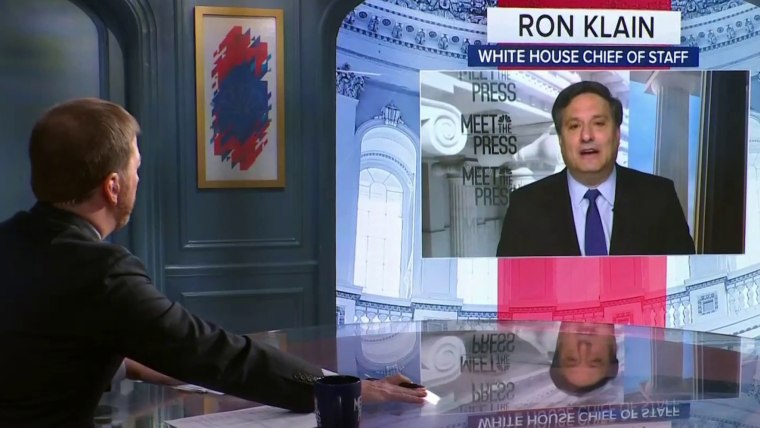

WASHINGTON — It’s a familiar Washington tale: As a president’s agenda stalls and his popularity dims, the search for a scapegoat often leads to his chief of staff. And as President Joe Biden looks for a reset at the start of his second year in office, the spotlight on White House chief of staff Ron Klain is especially bright.

From inside the administration, some officials express concern that Klain “micromanages” the West Wing and gives outsize credence to cable news and social media. Some former colleagues and longtime Biden allies fret that advice they used to offer Biden directly isn’t getting through. And on Capitol Hill, Klain has been a favorite target for Democrats, and especially Republicans, who say Biden has drifted too far to the left.

Senior White House officials counter that even the friendly fire from fellow Democrats doesn’t reflect reality. They attribute much of the grumbling to politics, personal score-settling and constraints that the coronavirus has put on Biden’s ability to reach out. Yet they also concede that Biden’s presidency is very much still taking shape.

This account of the West Wing’s inner workings and the scrutiny of the man who leads it is based on conversations with 30 administration officials, congressional officials and Democratic allies, most of whom spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss their concerns freely.

The main criticisms of Klain, whether from current or former Biden staff members or those who consider themselves allies of the president, flow from a single idea: that Biden has strayed from his core brand as a pragmatic, empathetic politician who won the Democratic nomination as a moderate willing to compromise. They see Klain as the person responsible for that. His ubiquitous presence on Twitter has solidified that view, particularly for those who see it as being out of step with a 2020 campaign that deliberately tuned out cable news pundits and “blue checks” on social media.

During the campaign — Klain wasn’t a formal member of, his critics are quick to note — Biden’s staff felt that the narratives on social media and cable news didn’t reflect the concerns of the coalition of working-class, suburban and African American voters that ultimately powered him to the nomination and then the White House.

Biden, however, seems to have been drawn into at least the cable news coverage of his presidency. Several Democratic lawmakers have reported getting unexpected phone calls from the president to applaud them for on-air appearances boosting his agenda.

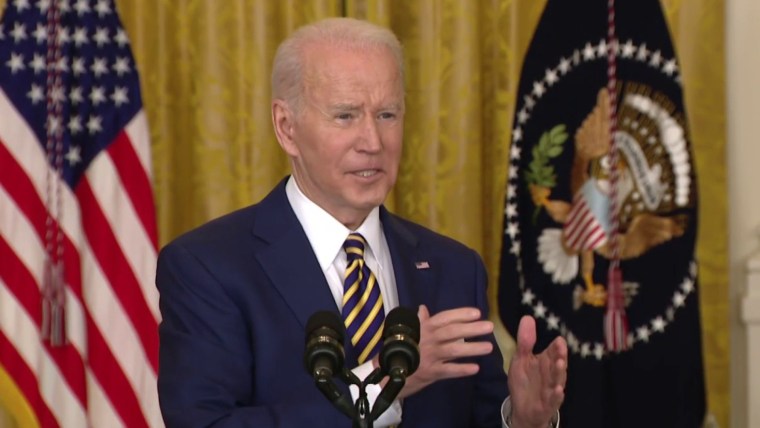

Klain’s critics also privately complain that he has a dated view of what it looks like to be presidential and that as a result, Biden is giving too many “one dimensional” speeches from behind a White House lectern, often responding to the crisis of the moment. From their point of view, Biden should be connecting more directly with the people the government is working for, not standing behind lecterns trying to convince them that the government is working. The White House plans to have Biden do more to reach out to Americans in the coming weeks as part of a year two strategy shift.

As part of that effort, Biden said this week that he would seek more advice from people outside his administration and that he plans to invite more lawmakers to fly with him on Air Force One. Soliciting more outside advice was a welcome promise for some of his former Senate colleagues and friends, who complain that they’ve been unable to reach Biden directly as often as they used to and see Klain as responsible for preventing him from hearing their perspectives.

Klain knows Biden “can be influenced by his old friends,” a longtime Biden friend said, adding, “And frankly, he should be, because there’s a lot of experience there.”

Part of the criticism of Klain is inevitable, White House officials and outside allies said.

“Things are not going well right now, so of course people are going to point to the chief of staff,” said a person close to the White House.

A president’s first chief of staff typically stays in the job for about two years. Former President Donald Trump replaced his first chief of staff, Reince Priebus, early, just six months after he took office. Former President Barack Obama’s first chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, left after the midterm elections.

Several outside allies said Klain is expected to stay through the midterm elections in November. White House officials said he hasn’t set a timeline for when he might leave.

And few expect any major changes in the upper ranks of the White House, which includes others like Klain who’ve worked for Biden for decades. Peppered with questions this week about missteps and disappointments in his first year, Biden at one point blamed the constraints of his office, rather than his staff.

“I find myself in a situation where I don’t get a chance to look people in the eye because of both Covid and things that are happening in Washington, to be able to go out and do the things that I’ve always been able to do pretty well — connect with people,” he said.

A senior White House official said that while Klain’s hands-on style might frustrate colleagues at times, it’s also an essential driver of decision-making among a team of advisers that has often been slow to make major decisions over Biden’s political career.

Multiple officials pointed to a process they said Klain has put in place to reflect Biden’s desire to hear advice and debate among the many longtime aides who populate his inner circle.

Each day in the West Wing begins with Klain presiding over a meeting of the “senior adviser group,” which includes counselor Steve Ricchetti, senior adviser Mike Donilon, deputy chief of staff Bruce Reed, deputy chief of staff Jennifer O’Malley Dillon, senior adviser Cedric Richmond, communications director Kate Bedingfield and press secretary Jen Psaki.

The group expands with top policy advisers as internal debates move forward, such as Domestic Policy Council Chair Susan Rice, National Economic Council Chair Brian Deese, national security adviser Jake Sullivan or Covid response coordinator Jeff Zients. And after those series of debates, advice is presented to the president.

“I’ve never seen a process that is so intentional to get input from everybody and then debate the course of action,” Richmond said. “Many times I’ve gone into meetings persuaded that I think ‘X’ is the right way. And actually listening to everybody and having a robust debate, I say, ‘Well, I’m changing my mind.’”

Klain, Reed and Ricchetti were all chiefs of staff to Biden when he was vice president, and they say they follow a similar process now when they brief their boss in his new role.

“Klain, although he has strong views, is exceptional at hearing everyone out, asking for a minority view [and] presenting it to the president,” Ricchetti said. Biden’s “not just looking for my view or Ron’s view. He’s looking for a broader perspective, a larger number of voices. And then he makes the calls.”

Rep. Colin Allred, D-Texas, who endorsed Biden early in the 2020 campaign, touting his ability to help vulnerable “front line” Democrats win in swing districts, said there have been “whispers” among some of his House colleagues about the dynamics of the White House team and which senior aides are their best advocates. But “I found that anything that I want to raise with them, I feel comfortable expressing it,” he said. “And the White House has really worked very hard to try and support me.”

Ricchetti said there’s no division between him and Klain among moderates or progressives, with each speaking regularly with a range of Hill Democrats.

“We are in and out of each other’s offices all day long. There just isn’t a phone call that we make that we don’t report to each other,” he said.

Richmond said any criticism of Klain should be directed at the larger team.

“I’ve played sports my entire life. So I know what a team effort looks like. And this is a good one,” he said.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com