In a time of grim uncertainty about the future, “Belfast” sent Kenneth Branagh and Ciarán Hinds reaching back into the past.

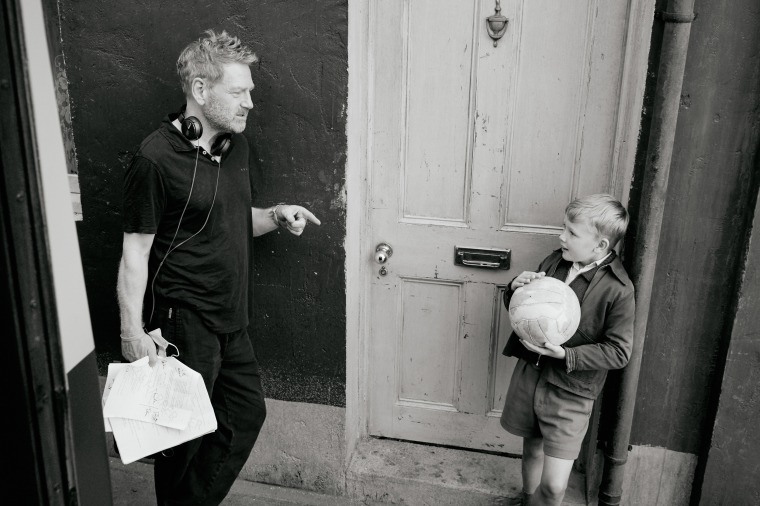

Branagh, who wrote and directed “Belfast,” saw the black-and-white coming-of-age film as a chance to dramatize memories of his childhood in the north of Ireland, an idyllic existence that was upended by the bloody political conflict known as the Troubles.

Hinds, who co-stars in the film as a kindly family patriarch modeled on Branagh’s grandfather, drew parallels between Branagh’s intensely personal script and his own formative years in the war-torn title city.

“Belfast” has clearly resonated with awards voters during another historical moment riven by national divisions and geopolitical chaos.

Branagh’s cinematic memoir is up for seven Academy Awards this year, including best picture, director, original screenplay and supporting actor, for Hinds. (The movie was distributed by Focus Features, a unit of NBC News’ parent company, NBCUniversal.)

In a joint Zoom interview this month, Branagh and Hinds discussed the personal realities that shaped their artistic creations. They also answered questions about the Oscars, the future of theatrical moviegoing and recent films they believe deserve a bigger audience.

The conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

NBC News: Kenneth, “Belfast” is one of 19 feature-length films you have directed since 1989. It seems to be your most personal project, with a story partly drawn from your childhood recollections. Why did you decide now was the right time to look into your own past?

Kenneth Branagh: I had wanted for a long time to write about Belfast because my attachment to the place remained so strong, and yet my memory of being wrested from it was still very tender.

As the lockdown began a couple of years ago, when we all felt uncertain and fear about the future consumed us, it really took me back to that time when I was nine years old. The relative security and relative harmony of the street where I lived was completely changed in the space of, it seemed, a couple of minutes, from a playground to a fortress.

What began was — for our family and for many other families in the north of Ireland — a period of incredible uncertainty and fear, where you had to navigate either living in and staying in an increasingly violent and dangerous situation, or considering whether you had any options to leave.

In the case of a large extended family in the community in which we were embedded, that decision is very formative and very emotionally charged. The film is the story of the highs and lows of navigating that journey through an uncertain, dangerous time to do what you think is best for your family.

Ciarán, I know you are also from Belfast. The film is a testament to the adage that it takes a village to raise a child. Pop, your character, provides patient and wise counsel to his grandson. I’m wondering how much of the character was based on people you knew growing up in midcentury Belfast.

Ciarán Hinds: Ken drew from incredible portraits of the community from which he came, his parents and grandparents. I found many similarities between the characters and my own family, my own grandparents — my mother’s parents, especially.

There was something about their stoicism and their generosity in tough times, their sense of being part of a community and helping where they could. But there were also memories of my own father: the warmth, his way of defusing potentially difficult situations.

I read the [script] and it really struck me that Ken had really hit the truth: the character and personality of those men of a certain age in Northern Ireland.

In recent decades, we’ve seen films, television shows and books about the Troubles that provide a decidedly grim, dispiriting look at that tumultuous period. But in contrast, “Belfast” seeks out moments of joy and childlike wonder.

Branagh: I think you’re right that what the story identifies is the necessity of joy for the family, in particular the nine-year-old through whose point of view we see the events of the story unfold. That’s critical, because the boy is not someone who can understand the complexity of objective political arguments. He just knows that now the street where you could once walk freely is now barricaded at either end.

That’s when his life starts to change. Men seem to be intimidating other men. Boys of his age start to be recruited for what seem like innocuous errands but might be something else. That’s how he encounters politics, and it’s scary and it’s suspenseful and it’s new. In part, it’s like living out the stories of the Westerns that he watches on television, or the movies that he goes to see.

But it seems to send him and his parents further toward any joy that can be found, any ad-hoc party, any of the other coping mechanisms that are part of the Irish tradition: song, poetry, music, dancing. He seizes on those things even in the grimmest of moments to try to put one foot in front of the other. They are the release value and the moments where clarity can be received.

The film consciously goes for a naïveté, if you like, that is partly inspired by that line about Picasso: he spent a few years learning how to paint and a whole lifetime learning how to paint like a child.

You mentioned that the little boy, Buddy, watches Westerns and other movies from the period. There’s a memorable scene where the family goes to the local cinema to see “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.” It’s suffused with affection and nostalgia for this family pastime: going to the movies. Are either of you concerned about the future of theatrical moviegoing?

Branagh: You couldn’t not be fearful, and yet you look at the success of “Spider-Man: No Way Home” and, in our own case, the success of “Belfast” at the U.K. and Ireland box office, in particular. The older audiences that seemed to be the least certain of going to the movies during the pandemic seem to be starting to return.

My feeling is: If you build it, they will come. Quality is necessary, but once you get back there, that reminder of what it’s like to have the group experience of responding to stories … I think if the work is good enough, the habit will be restored. It’s not easy, but I’m an optimist for the theatrical experience.

Hinds: There’s nothing like a lot of individuals coming into a cinema to watch a story that then binds every single member of that audience into one group of breathing, pulsing, feeling humanity as the story takes hold of their hearts. That’s something that cannot be replicated by streaming something. I think that’s why “Belfast” has connected people together in cinemas.

Ciarán, in the last four decades you have appeared in such an eclectic array of projects spanning so many genres. Can you tell me about a film or television project you’ve done that you believe deserves greater attention?

Hinds: Something starring me? “Oh, you’ve got to see me in this!” [Laughs.] There’s a very small independent film directed by an Irish writer named Conor McPherson, who Kenneth has worked with as well. He made a film called “The Eclipse,” which was about a man’s grief after the death of his wife.

It’s a beautiful film, but it also goes into the horror genre, because there are visitations. It’s a very delicate piece, and it’s not everybody’s cup of tea, but I think it’s well worth a watch. It suffered in comparison because, in the same year, there was another film out called “Eclipse,” and I think it was part of a big trilogy of vampiric things that was huge—

“The Twilight Saga: Eclipse”?

Hinds: That’s exactly what it was. The little “Eclipse” got overwhelmed by the big one.

I’d love to talk briefly about the Academy Awards. “Belfast” is up for seven awards, including best picture. The academy recently came under fire when it announced that eight of the 23 categories will not be presented live. What do you make of that decision?

Branagh: I think there’s a constant discussion about how our industry presents awards programs. Essentially, anyone who’s lucky enough for their work to be recognized is happy for it to be recognized on a level playing field. We know, more than anybody, that this is a team sport. The absolute instinct is that everybody who’s involved gets recognized in the same way and under the same terms.

But by same token, the challenges of ratings and what is deemed to be more or less televisual is a live debate. I’m sure the conversation isn’t over, you know? I think the reaction you mentioned will get heard and the matter may well be reconsidered.

I think I can guess which film you both will be rooting for on March 27. But are there other films released last year that you think deserve accolades? What were the films that stuck with you?

Branagh: Even with 10 best picture nominations, every year there are movies that don’t get looked at. From an unusual genre, or perhaps an atypical genre for such recognition, I would say that “Candyman” is a very, very, very expertly done horror movie, if it is a horror movie. It combines psychological thriller, excellent acting, genuine surprise in a really popular genre. Nia DaCosta did a really terrific job directing it. I personally got an enormous amount of pleasure from going to see that movie.

Hinds: I must check that out. That sounds extraordinary. [Laughs.] Two films I’ll mention. “Mass,” a beautifully acted film that held my attention and got me so emotionally engaged. It’s a 90-minute film and, of those minutes, 70 are just four people around a table. Extraordinary.

I also loved “The Humans,” which had a fantastic group of actors — Richard Jenkins, Jayne Houdyshell — and came from a play. It was shot in this strange, austere way. My heart kept beating faster and faster. I thought it was brilliantly made.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com