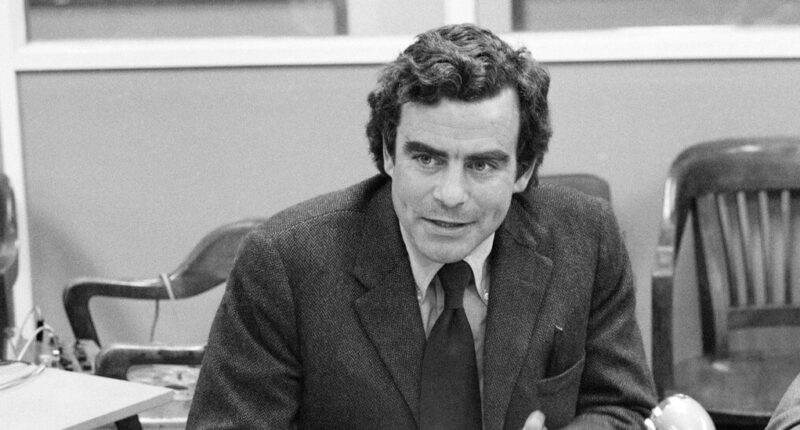

John Macrae III, a dashing publisher who gambled on groundbreaking books and dauntlessly defended authors who defied injustices committed by their own governments, died on Feb. 1 at his home in Manhattan. He was 91.

His death was confirmed by his wife, the Manhattan gallerist Paula Cooper.

Mr. Macrae was president and publisher of E.P. Dutton from 1968 to 1981, representing the third generation of his family to run the company. He then worked for 35 years at Henry Holt & Company, where he was editor in chief and later had his own imprint.

A fervent human rights advocate, he was chairman of the International Freedom to Publish Committee of the Association of American Publishers.

Mr. Macrae was among those who urged his fellow publishers to boycott the Moscow Book Fair in 1983 to protest the Soviet Union’s treatment of dissidents.

He flew to Poland with his son and a portable folding kayak to navigate the Vistula River and meet with anti-government leaders undetected. He then met with Lech Walesa, leader of the outlawed Solidarity trade union, and persuaded him to write his autobiography. Later, he helped smuggle the manuscript out of the country.

Mr. Macrae also championed Salman Rushdie when Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran in 1989 accused Mr. Rushdie of blaspheming Islam in his novel “The Satanic Verses” and enjoined Muslims to kill him.

“Jack traveled to Cuba and Iran on human rights missions,” Geri Laber, a founder of Human Rights Watch, said, noting that in addition to making “several trips on his own to Communist Poland,” he traveled to Communist Czechoslovakia to meet with the dissident playwright Vaclav Havel, later to become the Czech Republic’s first president.

Mr. Macrae also broke literary ground.

Among the noteworthy books he published were “Passages,” Gail Sheehy’s study of the stages of a person’s development from early adulthood to midlife crisis and beyond, which vaulted onto The New York Times’s best-seller list in 1976 and remained there for three years; David Levering Lewis’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “W.E.B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868-1919” in 1993; the American edition of “Wolf Hall,” Hilary Mantel’s Booker Prize-winning novel of Thomas Cromwell’s England, in 2009; and titles by the environmental activist Edward Abbey and the Argentine novelist Jorge Luis Borges.

“It was Jack who got me to go to San Francisco and meet Eric Hofer, the longshoreman-philosopher whose book ‘The True Believer’ had become a surprise best seller,” the New Yorker writer Calvin Tomkins said by email. “Jack published my biography of Hofer in 1965. Not many people read it, but that didn’t discourage Jack.”

He added: “Publishing was not about making money, he thought. It was about ideas, and we both felt that Hofer’s ‘True Believer’ was one of the important definitions of how totalitarian regimes take root.”

Amy Hertz, a former Dutton editor, wrote in The Huffington Post in 2010 that as a publisher Mr. Macrae “went after memoirs from apartheid South Africa and the end of the Cultural Revolution in China so that people would understand the suffering caused by lack of freedom.” And, she said, “he brought over the great Russian poets Yevtushenko and Voznesensky, and he worked with them to get Russian dissidents released from prison.”

“Jack’s brilliance,” Ms. Hertz added, “and what he passed along to me, is in not worrying about what’s on the page you’re looking at when evaluating a proposal or a manuscript. His brilliance is in hearing the thinking behind the author’s words, inchoate in the holy mess that when I worked for him was usually spread across his office floor. He taught me to find that kernel and to burnish it.”

John Macrae III was born in Manhattan on Nov. 21, 1931. He was a grandson of John Macrae Sr., who started working for Dutton as a 19-year-old clerk in the company’s New York City store, rose through the ranks and became president when the company’s founder, E.P. Dutton, died in 1923.

Jack’s father, John Jr., joined the company in 1921 as marketing director; he retired as president in 1974, when Dutton was sold to the Dutch publisher Elsevier. (Jack’s uncle Elliot, who died in 1968, had been Dutton’s publisher.)

John Jr. was best known for his innovative marketing of A.A. Milne’s “Winnie-the-Pooh” books in America (the first book was displayed for months in the window of Macy’s Herald Square store in Manhattan) and for publishing Mickey Spillane’s popular detective novels. Jack’s mother, Ann, was a homemaker.

Growing up in Westchester County, N.Y., Jack got to play with the original Winnie-the-Pooh and his coterie of stuffed animals, which Milne had given to John Jr. and which Jack later donated to the New York Public Library. (He had an affinity for real animals, too. Once, when threatened with hazardous winds and tides while kayaking off the Georgia coast, he was escorted to the safety of an inlet by dolphins.)

After graduating from the Kent School in Kent, Conn., he earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Harvard in 1954 while working for Dutton part time. Drafted into the Army, he served two years in Germany.

His marriage to Frances Cummins ended in divorce. In addition to Ms. Cooper, whom he married in 1987 and with whom he owned 192 Books, a store in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood, Mr. Macrae is survived by four children from his first marriage, John, Liza, Phebe and Annabel Macrae; two stepchildren, Lucas and Nick Cooper; six grandchildren; and one great-grandson, who was born after he died.

Mr. Macrae worked as an editor at Harper & Row before becoming president of Dutton in 1968. He remained with the company until 1981.

After Dutton was sold a second time — ending nearly a century of management by three generations of the Macrae family — Mr. Macrae was hired by Henry Holt, where he was editor in chief from 1983 to 1989. He retired in 2018 after publishing under his own imprint at Holt.

“He was probably the last of the old-time, gentleman WASP publishers — born into the business,” said Charles McGrath, a former editor of The New York Times Book Review. “He had immense personal charm, and it was hard not to get swept up by him.”

Late in life, Mr. McGrath added, “he found out he had multiple sclerosis, but didn’t let that slow him down. He zipped around the office — and the city, for that matter — in a motorized wheelchair, as cheerful as ever.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nytimes.com