Federal agents can run scans on things such as license plates and fingerprints to instantly find out who they belong to. But when it comes to guns, they’re essentially handcuffed by a 1986 law that keeps the ATF stuck in the past.

The nearly 40-year-old regulations prevent the agency from keeping searchable, digitized gun transaction records. And efforts in Congress to modernize the system have failed.

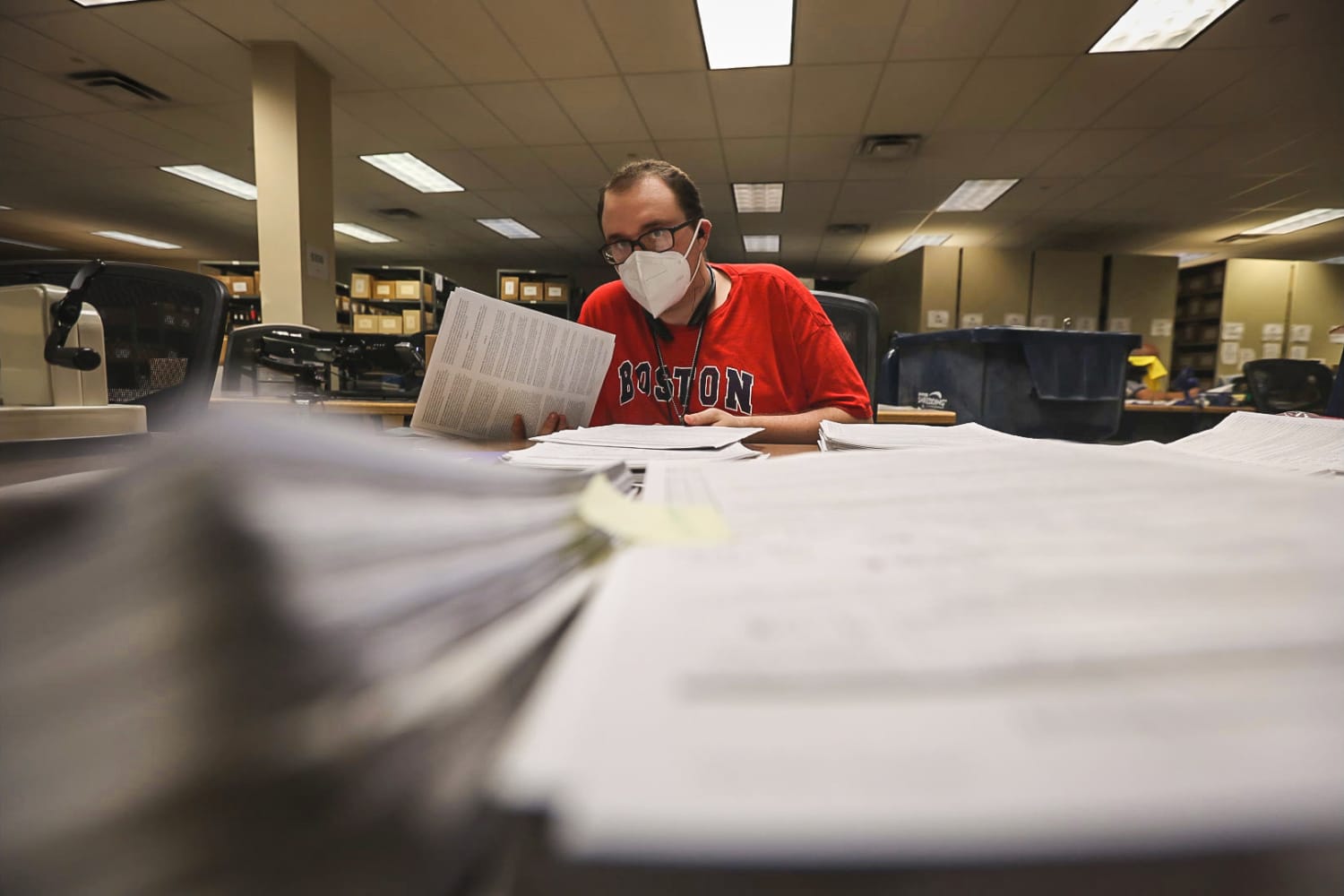

Boxes upon boxes of paper records fill nearly every corridor of the ATF’s tracing facility. The space was so cluttered that the agency brought in 40 cargo shipping containers, which sit outside the building, each filled with up to 2,000 boxes.

Today, the situation is more dire than ever. It takes 12 to 14 days for the ATF to perform a routine trace on a gun used in a shooting, robbery or other crime. The record wait time is due to a confluence of factors: shootings are up in cities across the country, ATF staff numbers are down, and more police agencies are seeking assistance in tracking the owners of firearms used in crimes.

“We are continually asked to do more, with less,” Neil Troppman, a program manager at the National Tracing Center, said after a tour of the facility earlier this summer.

The recent mass shootings in Buffalo, New York, and Uvalde, Texas, have renewed attention on the ATF’s archaic system for tracing guns. But the bipartisan gun legislation signed into law in June doesn’t include any measures to modernize the nation’s only gun tracing facility.

Congress remains divided over expanding the capabilities of the ATF. Senate Democrats sponsored a bill last year that would allow the agency to keep a gun tracing database to aid law enforcement, but it went nowhere.

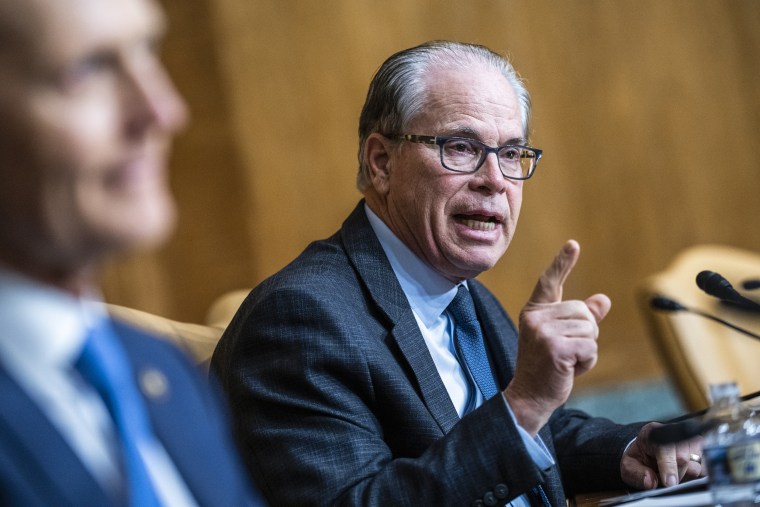

Republicans have long argued that allowing police access to an electronically searchable repository of gun records is tantamount to a nationwide firearm registry, which would make it easy for the government to seize people’s weapons. In April, 18 GOP senators signed a resolution opposing Biden administration regulations that will require gun dealers to retain their entire history of transaction records.

Only two of the 18 responded to an NBC News request for comment.

Sen. Mike Braun, R-Ind., suggested in a brief interview that he was open to the idea of allowing the ATF to create searchable electronic databases.

“It seems to be something that would seem to make sense,” he said while walking to a Senate vote.

Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, said in a statement that Democrats should focus on prosecuting criminals and “those with serious mental illness,” rather than “undermining the rights of law-abiding citizens by creating a national gun registry.”

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., who co-sponsored the Democrats’ doomed bill with Sen. Patrick Leahy of Vermont, said that’s not what members of their party are seeking.

“All this would do is bring the ATF into the 21st century and allow them to search the data they already have quickly,” she said in an interview.

The rise of gun control

The birth of modern day gun control came in the wake of two assassinations that rocked America.

The killings of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy led to the passage of the Gun Control Act of 1968, which required gun dealers to get a federal license to operate and also made them write down the names of people buying their weapons.

Since its establishment in 1972, the ATF has been tasked with tracing firearms used in crimes. But in 1986, then-President Ronald Reagan, under pressure from the gun lobby, signed alaw that prohibited federal law enforcement from using “any system of registration” of firearms, firearm owners or firearm sales.

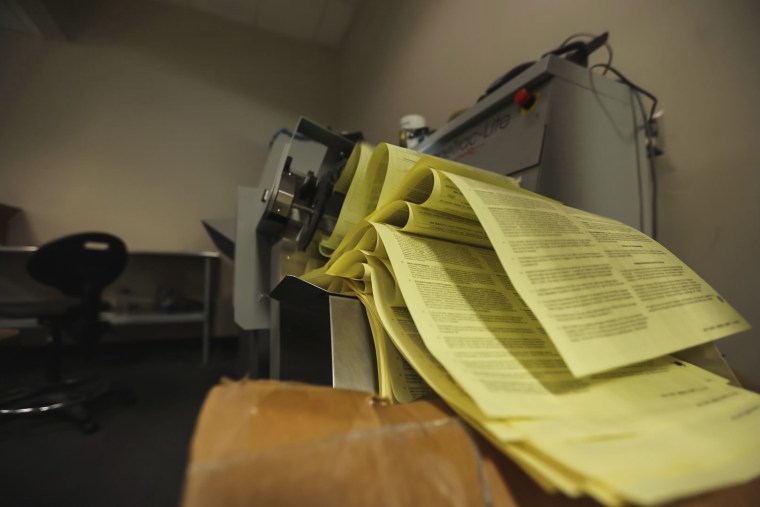

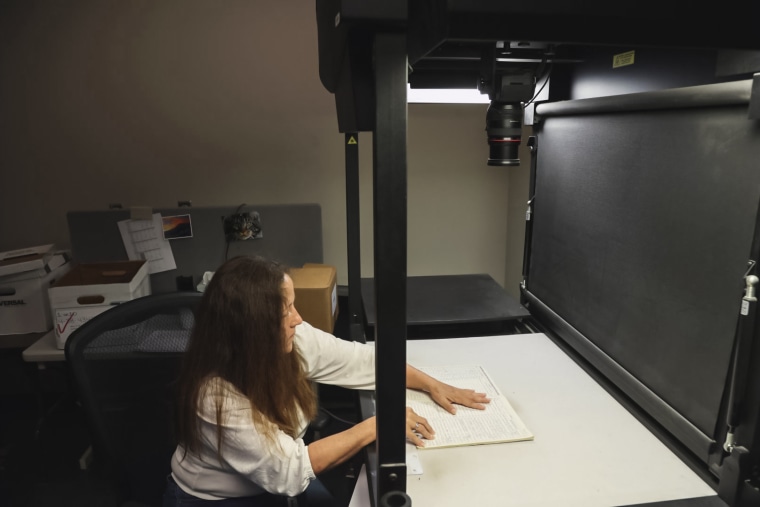

Troppman said that when he joined the center during the mid-1990s, staff would convert paper gun records into microfilm. Nowadays, tracing center employees use high-powered scanners to input the documents onto computers.

But they must walk a fine line when using 21st century technology in order to avoid running afoul of federal restrictions.

If the gun shop records are in an Excel file or another electronic format, the data extraction specialists are called in to make screenshots. Despite having access to more than 900 million scanned records, the ATF can’t look up gun owners or shops by name. When a trace comes in, investigators have to scroll through hundreds of pages of screenshots to find the gun information.

The trace requests now pour in at an unprecedented rate, thanks to an online portal called eTrace. The system allows local law enforcement agencies to file trace requests with just a few keystrokes, while the ATF investigators must scroll through hundreds of pages of screenshots to find the information needed to solve crimes.

“It is stupid. It is outrageous. And I blame Congress,” Leahy said in an interview, referring to the two-week wait time on routine gun traces.

While most take up to 14 days to complete, expedited searches are usually done for homicides and mass shootings, including on the AR-15-style weapon that was used to kill seven people at a July Fourth parade in Highland Park, Illinois.

According to the U.S. Justice Department, 83% of “urgent requests” are completed within 48 hours.

The ATF is flooded with a record number of trace requests at a time when it’s facing a serious staffing shortage. The agency had about 80 federal employees assigned to the tracing center in the 1990s. It now has roughly 55.

In order to keep the nation’s gun trace effort afloat, the ATF relies on hundreds of contract workers, assigning them to organize and scan the millions of gun records that flood the facility each year.

If the agency stopped receiving records today, Troppman said, it would take about 14 months to clear the backlog. The work ahead is on full display at the ATF’s West Virginia facility, which looks like a time capsule from the era that birthed MTV.

Inside the National Tracing Center

On a recent Thursday, a gray-haired woman sat hunched over a pile of gun purchasing forms from 2013, thumbing for clues. Across from her, a young man clawed through box after box fishing for the one document that might reveal who owns the weapon found at a recent crime scene.

“Despite what people think, it’s still a manual process, regardless of what technology is out there,” Troppman said.

The ATF often has little trouble tracking the first few legs of a firearm’s journey from factory to wholesaler. More than 30 gun manufacturers, distributors and importers came up with a workaround to speed up gun traces since, unlike the ATF, they can keep electronic databases.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com