A huge basin on a tiny island off the coast of Sicily, long thought to have been an ancient harbor, was actually a sacred freshwater pool surrounded by Phoenician temples and aligned to the stars, according to a new study.

The depression, larger than an Olympic swimming pool, was unearthed on the southwestern shore of the island in the 1920s. It was thought then to be a “kothon” — a fortified harbor used to protect naval ships at other Phoenician cities, such as Carthage on the coast of North Africa.

But recent excavations led by Lorenzo Nigro, a professor of archaeology and art history at the Sapienza University of Rome, show it wasn’t originally connected to the sea, so it can’t have been a harbor.

Instead, the basin was separate from the sea and fed by three freshwater springs, something seen in ancient times as a sign of divine favor, Nigro said.

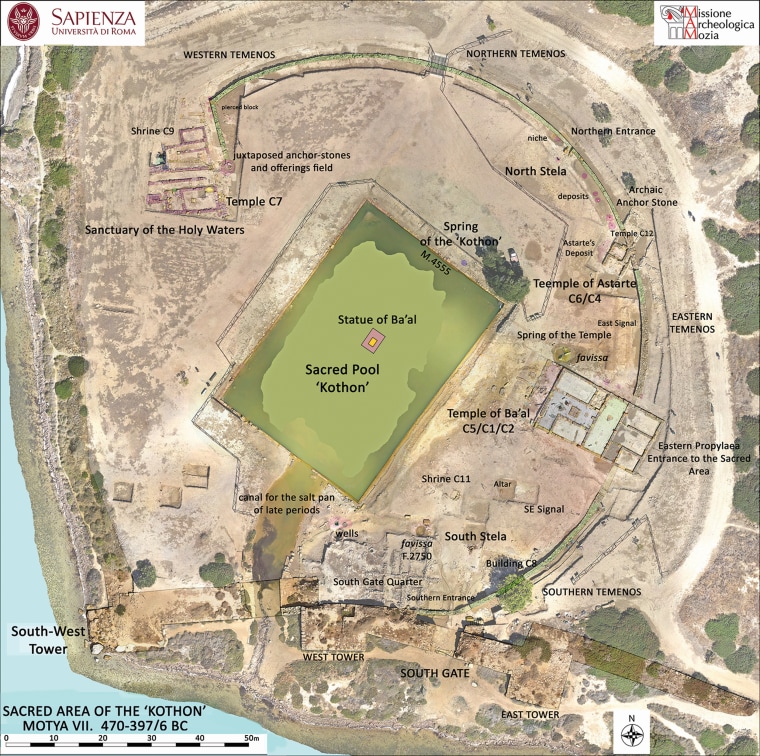

A study of the discoveries was published Wednesday in the journal Antiquity, revealing that the basin at Motya was part of one of the largest religious complexes in the ancient Mediterranean, which connected the Phoenician colonists with the traditional beliefs of their homelands. The basin also may have allowed the Phoenicians to study the changing positions of the stars and planets, which were crucial to their ships’ navigation.

The Phoenicians are thought to have pioneered navigation by the stars and to have introduced innovations like the alphabet, glass and the vivid “royal purple” dye across the Mediterranean, making any new information about them of considerable interest.

The Phoenicians were a seafaring and trading people from the eastern Mediterranean who’d founded a city on Motya in about 800 B.C., along with other colonies on Sicily.

Motya became powerful enough to go to war for a time with Carthage, another Phoenician colony, and the basin was constructed in about 550 B.C. when the city was rebuilt after a Carthiginian raid. It was abandoned in Roman times.

The kothon at Carthage protected its warships during the Punic Wars against the Roman Republic, when each side vied for mastery of the western Mediterranean. (It was a close-run thing, but the Carthaginians eventually lost.)

The basin at Motya — it’s still being called a kothon — turned out to be interesting in a very different way. The sea level has risen almost 3 feet since it was built, and part of it was used for a while to produce salt from seawater. But the recent excavations established it was constructed as part of a sacred compound.

Nigro has worked at Motya for two decades, since before the site was known to be religious in nature. About a dozen years ago, the remains of a temple to the god Ba’al — a chief of the Phoenician pantheon — were found beside the basin instead of the expected harbor buildings.

A statue of the god, more than 10 feet tall, once stood on a plinth in the center of the sacred pool. The stone blocks portraying its feet were reused in a wall at the site long after the city was abandoned, and its torso was found in the lagoon in the 1930s. Its head, probably wearing a horned crown, has never been found.

The pool has now been cleared and refilled from the springs. A replica of the statue has been placed on the plinth as a tourist attraction and to show archaeologists how the site functioned.

“This really made sense of the whole area,” Nigro said. “Then we understood that everything was around the statue. … You can see from every point that the statue was the focus of the architects, that the god was the overlord of the waters and of the skies.”

He suggested that reflections in the surface of the pool were used to keep track of celestial movements, which were important for both religious holidays and for navigation — especially the prominent constellation of Orion, which was aligned at the midwinter solstice with the main temple.

“It possibly was used to measure the movements of stars — this was very important because ancient people needed to measure time and distance, because they needed to navigate,” he said.

The sacred compound was surrounded by a circular temenos, or holy area, within which several standing stones were placed. “The area is full of these stones, which are set in some spots of the circle possibly according to observations of the stars and planets,” he said.

Helene Sader, a professor of archaeology at the American University of Beirut who wasn’t involved in the study, noted that sacred pools were a key part of many temples in the Phoenician homelands, which roughly correspond with modern-day Lebanon.

“The Motya temple complex around a pool is not an oddity in the Phoenician religious context,” she said in an email.

Gunnar Lehmann, the head of the archaeology department at Israel’s Ben-Gurion University and a specialist in Phoenician archaeology, said Motya would have been an important stop for ships between Phoenicia and the western Mediterranean, where their colonies in Spain and Sardinia traded for metals to ship to the ancient Near East.

“The city must have acquired considerable wealth to construct such monumental sanctuaries,” he said in an email. “Nigro’s research demonstrates how close the Phoenicians in the western Mediterranean remained to their original culture.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com