“What was the worst part about Covid? Besides masks, of course.”

That was the question one of my school administrators greeted me and my fellow Texas classmates with on my first day as a high school junior in August.

Sure enough, only a few weeks after settling into school life, almost a fifth of my English class had been out sick.

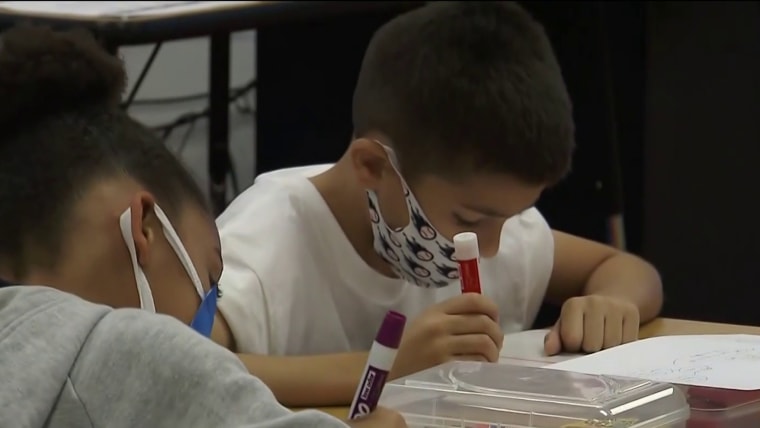

It was the first time that I had set foot in a physical classroom in almost two years. But instead of beaming with the excitement of returning to in-person schooling after completing both my freshman and sophomore years online or thinking about typical back-to-school questions like whether I had any classes with my friends or who my teachers were, I was rattled at hearing my administrator refer to the coronavirus in the past tense. It was even more unnerving to notice that, out of the 90 or so students sitting beside me at the assembly he was addressing, fewer than a sixth were wearing masks.

Stepping back on campus, I saw throngs of students jammed into the hallways like sardines without any protection from mask or vaccination mandates. The school was acting as if a pandemic hadn’t been raging for 18 months and as if Texans weren’t still dying from Covid every day. After taking one look at the scene, my friends and I, using a dark coping mechanism, joked that it would be impossible not to get infected.

Sure enough, only a few weeks after settling into school life, almost a fifth of my English class had been out sick. In September, roughly 50 students in my district were testing positive each day. My phone, once used for scheduling movie nights and birthday parties, became a ticking time bomb as I anxiously awaited PCR test results from my closest friends while group chats brimmed with quarantined students cracking under the stress of juggling their schoolwork and their Covid symptoms without a virtual learning option.

Now, on break for Thanksgiving at the start of a holiday season widely expected to jack up infections even more, nothing has changed: My school’s Covid policies are still lax, and students are still getting sick. Yet even as the coronavirus uproots education as cases spiral out of control, with upward of 220,200 Texas students having been infected since August by this highly contagious and potentially deadly virus, student safety is never at the front lines of our conversations. Masks are.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends universal mask-wearing for K-12 schools, while the scientific consensus is that masks save lives. Meanwhile, stuffy, crowded classrooms and cafeterias, close-contact sports and activities like marching band only inflame Covid transmission at the same time the hypercontagious delta variant circulates. To make matters worse, only around half of teenagers ages 12 to 17 have been fully vaccinated, with 30 percent of parents reporting that they would “definitely not” get their children inoculated.

And yet, in a school system where teachers and staff members won’t impose the commonsense protection of a mask mandate, students concerned about the pandemic are left to fend for themselves during a time of life already full of transition and uncertainty. Rope that together with the social pressure of high school and students are bearing the brunt of anti-masking — including standing out by choosing to mask with no mask mandate in place.

Sure enough, only a few weeks after settling into school life, almost a fifth of my English class had been out sick.

To keep myself and others safe, I wear a mask when I go to school. Most of my friends do, as well. But the overwhelming majority of my school has chosen to scrap them. Masked students have been grilled on exactly why we’re wearing masks, adding to the enormous peer pressure facing anyone at this stage of young adulthood when popularity, appearances and social points matter more than ever. When a fellow student council officer told me, “At least we don’t have to wear masks anymore,” I shifted awkwardly in my mask, feeling like I was supposed to take it off.

There’s also the indirect pressure of missing out on quintessential high school experiences. As teens sacrifice what is touted as some of the “best years” of their lives to stay safe, the fallout from skipping milestone moments like homecoming football games and prom can be crushing — but it’s often the simplest high school experiences that matter the most. “As I stay home, my closest friends continue to get together on a regular basis, without masks,” my good friend Sam, also a junior in my school, told me. “It’s extremely difficult to balance social life and my concern for health, and I ultimately feel more secluded from my friends than ever before.”

We also face political pressure, because masks have mutated into an intensely politicized issue rather than what they’re meant to be — a form of protection. My peers have reposted photos on social media of mask burnings and infographics dubbing the mask a tyrannical form of governmental control and a metaphor for sickness, gullibility and irrational fear.

During fiery school board meetings in my district, parents armed with pseudoscience fight for their children’s “right to breathe.” In San Antonio, the police were called to disperse a rowdy anti-mask group that had gathered in front of a school to harass students and staff members. In another incident, in Austin, a parent physically ripped a mask off a teacher’s face.

The pressure doesn’t let up, especially for students who face more than a handful of school absences if they get sick. Mia, one of the only students wearing a mask on the drill team at my school, is susceptible to autoimmune disease, which prevents her from getting vaccinated. In other words, masks are virtually her only line of defense. “It is definitely a little awkward to be one of the only ones wearing a mask,” she said. “There are lots of times I wish I could take it off because of the constant judgment.”

Other students know firsthand that the effects of anti-masking they might experience at school come home with them. My friend Julia, a junior, thinks of her immunocompromised brother. He survived cancer and couldn’t get vaccinated until recently because of his treatment. “Masks don’t just affect you or your family or your classmates,” noted Julia, who continues to wear a mask in solidarity with other immunocompromised people. “They affect all of those people plus their loved ones, their family and friends.”

As much as I want to leave my mask at home, and as much as I want to get “back to normal,” every single student deserves to feel safe, and so do their family members and friends. This precarious balancing act of being a student during a pandemic is being made even more challenging because we lack the support system and safety measures of a school that takes Covid seriously.

When schools are caught in the chaotic and terrifying crosshairs of a pandemic that targets vulnerable students, wearing masks shouldn’t be up for debate — it should be a civic responsibility. That’s what my school administrator should have told us on the first day of school this year.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com